The security crackdown in Xinjiang announced in May has done little to quell violence in the region, with a number of attacks in recent days that have killed dozens of people, perhaps many more. Restrictions on independent reporting make it difficult for journalists and others to investigate the details of specific incidents, with most reports coming from official sources. The government has blamed the violence on the rise of religious extremism from abroad, while some observers have said that government policy has exacerbated grievances that have found their outlet in violent acts.

Authorities recently said that 96 people died in an incident in Shache, Xinjiang on July 28, calling it an “organized and premeditated attack” in which knife-wielding assailants stabbed motorists along a highway. But Barbara Demick of the Los Angeles Times has heard conflicting reports indicating that the violence may have been sparked by a security raid of an Eid al-Fitr gathering. She writes that the incident is “so shrouded in mystery that it would seem that nearly everybody who witnessed it took an oath of silence — or is dead”:

A resident of the town said the trouble began July 27 when Muslims were preparing for the Eid al-Fitr holiday, which ends the holy month of Ramadan. About 40 women were detained for wearing clothing deemed excessively Islamic, which is banned in Xinjiang.

“There was a religious gathering, which the security thought was illegal. A large number of security forces came. There was a confrontation and things escalated,” Kuerban said. He said he was told that 15 to 20 people were shot at the gathering and that riots spread afterward to nearby villages.

[…] Authorities allege that there was an “organized and premeditated” attack in which assailants armed with knives and axes ambushed cars and trucks on Route 215, the main road south into the town.

They identified the mastermind as Nuramat Sawut, a former imam who had links to the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, a separatist group operating across the border in Pakistan. [Source]

Recent restrictions on cultural practices by Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, including bans on beards and traditional clothing on public transportation and on fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, are irritants in an already tense relationship with Han authorities. An editorial in The Economist argues that Chinese authorities need to show more respect for Uyghur cultural practices in order to ease tensions:

Whenever violence flares up, the government’s rhetoric is uncompromising and usually focused on the dangers of jihadism. In May, following a spate of attacks by Uighurs on government and civilian targets in Xinjiang and in other parts of China, Mr Xi demanded “walls made of copper and steel” and “nets spread from the earth to the sky” to catch the “terrorists”. The party blames such attacks on Islamist militancy seeping across the border from Central and South Asia—notably from Afghanistan and Pakistan. It likes to claim that Uighurs live in harmony with the Han Chinese (“tightly bound together like the seeds of a pomegranate”, as Mr Xi puts it).

The tragedy is that the government could end up proving itself right—by making jihadism the core of the Uighurs’ militancy. For now the violence is fuelled principally by a welter of home-grown grievances and is strikingly amateurish: rarely are the perpetrators armed with anything more than knives. But in recent months the violence has been morphing, spreading beyond the region itself and taking on some of the hues of jihadism elsewhere—through suicide-attacks and indiscriminate killing of civilians.

Such acts are unspeakable. But there is evidence that China’s heavy-handed approach in Xinjiang is radicalising a once-tolerant culture. Uighur activists abroad say the latest violence near Kashgar had nothing to do with terrorism, for instance; instead it was sparked by police efforts to enforce government bans against fasting during Ramadan. [Source]

Beijing has tried to quell growing resentment by funding development in the region, but so far these efforts have come up short. From another article in the Economist:

Relations between Han Chinese and Uighurs in the region have deteriorated sharply since 2009, when clashes erupted in Urumqi between Uighurs and Hans, leaving around 200 dead. The government has responded by pouring in money. Xinjiang is due to be connected to the rest of China by a bullet-train track later this year; Kashgar is soon to be connected by expressway to the north of Xinjiang, which officials say will boost the city’s economy. But Uighur grievances have been exacerbated by officials’ intolerance of Islamic traditions and their emphasis on Chinese instruction in schools. Kashgar itself, an historic Uighur market city on the old Silk Road, has demolished and rebuilt vast areas of ancient neighbourhoods, heedless of residents’ complaints. [Source]

While putting forth the carrot of economic development, government officials have also been taking an increasingly tough line on security in the region. Public Security Minister Guo Shengkun visited Xinjiang in the wake of the Shache attack and announced that the fight against terrorism “should reach every single village and household”. Adrian Wan at the South China Morning Post reports:

Guo toured the far western region at the weekend and told the authorities that the fight against terror had to reach into all areas so that long-term stability could be maintained, state media reported.

Guo also told officials they needed to significantly strengthen their intelligence gathering to prevent attacks. [Source]

But some observers, like the Economist editors above, fear the government’s tactics are fueling violent extremism instead of preventing it. From Deutsche Welle:

“There is clearly a causal link between hard-line law enforcement and Uighur violence,” says [Edward] Schwarck, explaining that bans on everyday expressions of Uighur culture are “deeply provocative and frequently spark violent reactions.” Now there are fears that the increasing repression of their culture is leading to radicalization among the Uighurs, WUC vice president Hamit told DW. The government then accuses them of terrorism, leading to a vicious circle of violence.

Accusations are flying from both sides – while Beijing blames recent attacks and violence on Uighur “terrorists,” the Uighurs deny these claims. [Source]

As Dan Levin reports in the New York Times, some Uyghur women are making their own show of defiance by embracing traditional religious clothing and practices as a way to oppose government restrictions and assert their identity. One Uyghur woman living in Beijing tells Levin: “The more the Chinese government forces us to live a Han lifestyle, the more we will find ways to express our Uighur identity”:

Despite the cheerful propaganda, veils have become a point of contention for violent clashes. In May, protesters in southern Xinjiang beat up a school principal they had accused of helping the authorities round up female students wearing head scarves. Police officers opened fire on the angry crowd, killing at least four people, Uighur activists say. In June, four Uighur men were shot and killed during a confrontation with officials who had lifted a woman’s veil during a house inspection.

The battle over the female dress code is part of a larger struggle over what it means to be Uighur in Xinjiang, a place long known for its moderate brand of Sunni Islam. Though some Uighur women cover their hair and faces for religious reasons, a growing number appear to be embracing the practice as a gesture of quiet defiance. “Whenever I go home to Xinjiang, I wear a head scarf to show that I cherish my culture,” said Luna, the business translator. [Source]

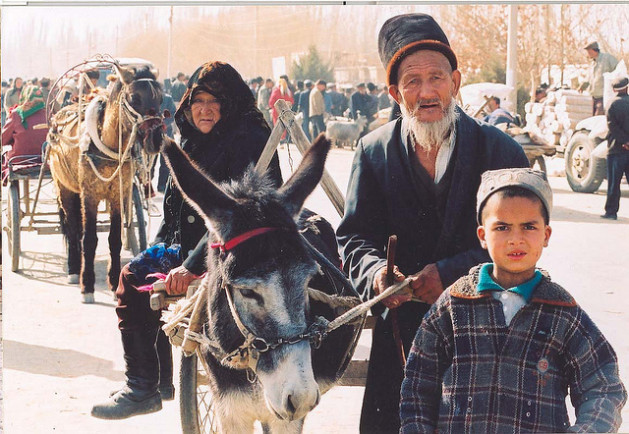

Getty Images photographer Kevin Frayer has taken a series of images of daily life for Uyghur residents of Kashgar and other areas of Xinjiang. His photos can be viewed via the Washington Post and the Guardian.