Last week, the the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China released a paper on the deteriorating reporting conditions that face foreign journalists working in China, including a list of over two dozen recommendations to Beijing. The New York Times summarizes the paper and provides examples showing the increasing difficulty for correspondents working in China:

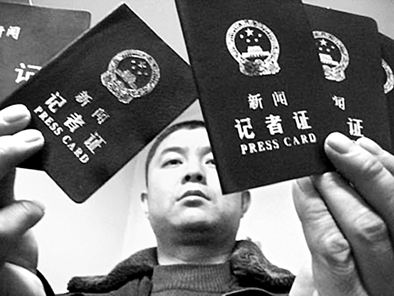

The report, the result of a survey among the organization’s 243 members, paints a portrait of mounting pressure on foreign journalists as the ruling Communist Party seeks to aggressively limit negative coverage abroad and to punish news organizations and reporters who defy warnings to steer clear from so-called sensitive topics, such as the wealth accumulated by relatives of China’s top leaders.

[…] The report details increasing harassment of foreign journalists by public security personnel, with two-thirds of respondents reporting interference or physical violence in the field. […]

[…] In some instances, the police have sought to intimidate reporters by visiting their homes and bureaus. In the weeks before the 25th anniversary of the June 4 military crackdown on student protests in Tiananmen Square, several reporters were summoned to the offices of the Beijing Public Security Bureau and warned against covering the occasion.

[…] A number of other American news organizations have been thwarted in their effort to establish bureaus here. According to the report, PBS NewsHour, Huffington Post and the online news organization GlobalPost have been denied licenses to set up offices in China. A reporter for Huffington Post living in Beijing has been granted a six-month temporary journalist’s visa rather than a longer-term journalist’s residency visa.

Large portions of the country remain off-limits to foreign correspondents. In addition to the restricted access to Tibet, the government has made it increasingly difficult for reporters to conduct interviews in the far western region of Xinjiang, home to China’s Uighur minority, as well as to heavily Tibetan areas of Gansu, Sichuan and Qinghai Provinces. The report described such restrictions as “widespread, arbitrary and unexplained” by the authorities. […] [Source]

China’s escalating pressure on foreign reporters comes as the domestic press also faces increased regulation—part of the Xi administrations larger crackdown on dissenting opinion among the Party, the academy, the media, and the public.

Meanwhile, press freedom advocacy groups have noted Beijing’s expanding influence over Hong Kong’s relatively free press. After several recent attacks on reporters and as Beijing leverages its economic clout to encourage self-censorship, the HK Journalists Association declared this year the “darkest for press freedom” in several decades. In July, Hong Kong-based web outlet House News shut down citing political pressure, and last month pro-democratic paper Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai said millions of advertising dollars had been pulled from the paper due to their coverage of protests in the region.

Following the Foreign Correspondents’ Club’s recent paper, the Overseas Press Club of America issued a statement urging China’s leaders “to reverse course and enforce their own laws requiring free speech and press freedom.” The statement identifies the preservation of Hong Kong’s free press as an essential element for encouraging free speech in the mainland:

[…F]or decades, Hong Kong has been an oasis of free speech and a robust media—both among local media and journalists from around the world who have been based there. This status is now at risk.

Recent alarming events in Hong Kong demand urgent focus. In 1984, China signed an international treaty, the Joint Declaration, expressly guaranteeing press freedom in Hong Kong and the continued application of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This treaty is registered at the United Nations.

The escalation of violent attacks on journalists and demands from China’s Central Liaison Office for censorship and to cease advertising in independent media are causes for great concern. If Hong Kong loses its free flow of information, the territory will quickly lose its status as a global financial center.

Press freedom is most likely to advance over time in China if it is preserved today in Hong Kong. [Source]