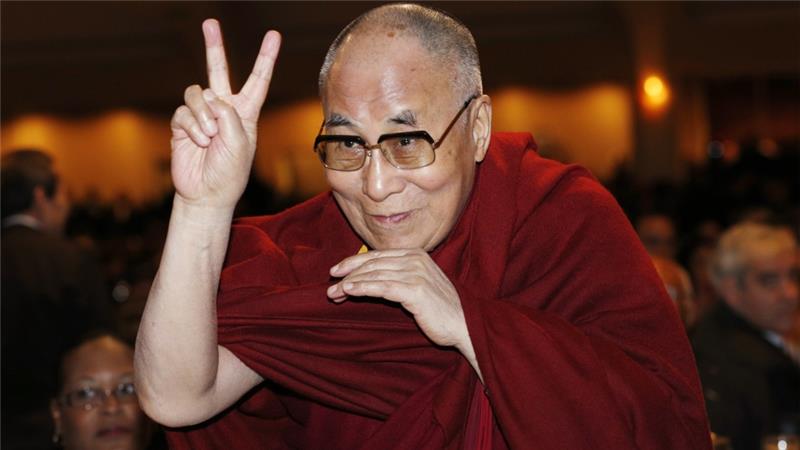

Currently on a tour of Europe, the Dalai Lama had lunch on Sunday with Slovakian president Andrej Kiska. The meeting has unsurprisingly drawn protest from Beijing. At Reuters, Ben Blanchard reports:

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said Kiska had ignored China’s “strong opposition” to the meeting, which was contrary to the “one China” policy the Slovak government has promised to uphold.

“China is resolutely opposed to this and will make a corresponding response,” Hua told a daily news briefing in Beijing, without giving details.

[…] Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua said the Dalai Lama has long tried to separate Tibet from China and the government opposes any foreign official having any form of contact with him. The meeting has “broken the political basis of China-Slovak relations”, Hua said.

“We demand the Slovak side clearly recognize the anti-Chinese separatist nature of the Dalai Lama clique and earnestly respect China’s core interests and major concerns.” [Source]

Reuters last week reported on the Dalai Lama’s stop in Switzerland, where he urged young Swiss-Tibetans to “have the courage and determination to support the Tibetan cause[…] For that you need to understand the richness of the Tibetan culture.”

The Chinese government considers the Dalai Lama a separatist despite his decades of advocacy for genuine Tibetan autonomy within China. Regular protest from the Foreign Ministry over foreign leaders’ meetings with the 81-year-old exiled Tibetan spiritual leader has resulted in less diplomatic engagement with Western leaders in recent years. Late last month, The Guardian ran an editorial calling for resistance to Beijing’s anti-Dalai Lama diplomatic efforts on the world stage.

In 2014, the Dalai Lama praised Xi Jinping for being “more open-minded” than previous Chinese leaders, and hinted that informal discussions may soon win him a pilgrimage to China. Beijing responded by strongly reasserting it’s anti-Dalai Lama stance, and promising to “severely punish” Party members in the Tibet Autonomous Region who support him. Also in 2014, the Dalai Lama twice publicly suggested that he could be the last incarnation in a centuries old political and spiritual tradition. Beijing countered by demanding its right to name his successor. A report last year from Reuters offered evidence that Beijing has long been supporting a schism within Tibetan Buddhism by supporting a controversial minor deity in order to harm the Dalai Lama’s global reputation.

Last month, Wu Yingjie, the newly appointed Party secretary of the Tibet Autonomous Region, pledged to “deepen the struggle against the Dalai Lama clique, [and] make it the highest priority […].” Party authorities have also recently shown signs of plans to groom their controversial choice of the 11th Panchen Lama to act as the Dalai Lama’s successor after his death.

Beijing’s attempts to oversee Tibetan Buddhist affairs is based on the official interpretation of history, which situates the Party as inheriting stewardship of Tibet from its imperial predecessors; however, the case of the Tibetan independence movement too relies on a different interpretation of history. Last week at The Washington Post, Simon Denyer reported on a nightly opera featured in Lhasa, mostly for an audience of tourists, which promotes Beijing’s version of history:

The story of Princess Wencheng Gongzhu and her marriage to Tibetan Emperor Songtsen Gampo is the subject of a multimillion dollar opera that plays most nights for tourists in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. It plays out under the stars on a vast stage, with a cast of hundreds and a vast replica of the Potala Palace.

But this is more legend than history, and more propaganda than legend.

Historians say the tale of Princess Wencheng has been twisted by Communist China to justify its 1951 occupation — or “liberation” of Tibet.

[…] This is a version of history commissioned and shaped by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, according to Aarhus University associate professor Cameron David Warner.

Zhou commissioned Communist playwright and composer Tian Han (who also penned the national anthem of China) to write a play about the life of the princess in the wake of a Tibetan uprising in 1959 and subsequent repression. […] [Source]

The theatrical representations of folk stories have also been used to bolster Beijing’s claims to Xinjiang, another minority region mired in political and ethnic tension. The Washington Post’s Denyer had earlier this month reported on authorities’ strategy of promoting tourism in Tibet as a “new engine for development,” focusing on critics’ fears that such efforts are trivializing Tibetan culture, further marginalizing Tibetans, and harming the region’s fragile environment.