The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

Regarding the article “Beijing Prosecutors: No Prosecutions for Five Police Officers Involved in Lei Yang Case,” all websites, WeChat and Weibo accounts, and media apps must strictly control related comments. Please immediately acknowledge receipt of this notice. (December 23, 2016) [Chinese]

In addition, Sina Weibo searches for “Lei Yang case” (雷洋案) produce the notice that “in accordance with relevant laws, regulations, and policies, search results [for this term] are not displayed.” Users have further reported automatic blocking of comments on all Sina Weibo posts including the phrase.

On May 7, Lei Yang, a 29-year-old Renmin University graduate and recent father, died after an encounter with Beijing police. Authorities claimed he died of a heart attack after trying to flee from arrest for soliciting a prostitute on May 7. His family, on the other hand, said that he was on his way to pick up relatives from the airport, and it soon emerged that the “heart attack” was a fabrication meant to hide the violence of his arrest. An investigation into the five officers involved was launched in June, but on Friday the Beijing Municipal People’s Procuratorate announced that the probe had ended with the decision that their “mild criminal behavior” did not warrant prosecution. An official Q&A on the case conceded that “there was a direct causal relationship between Lei’s death and the inappropriate professional conduct of Xing and the other officers involved, but Lei’s own fierce and persistent resistance in his over-fed state was also closely related to the fatal outcome.” The AP’s Gerry Shih reports:

Prosecutors said in June that an autopsy showed that Lei suffocated on his vomit while in a police vehicle rather than dying from a heart attack, as noted in the police report. Police also sought to block an initial investigation into Lei’s death, prosecutors said.

Lei’s friends and commentators also have questioned why the struggle was not filmed — the officers said all their video recording devices were broken — and why it took so long for medical help to arrive after Lei fell unconscious. Lei’s family also said his head was covered with bruises.

[…] The agency also noted that the officers acted improperly not only by failing to promptly administer first aid to Lei but also by “deliberately fabricating facts, concealing the truth and hindering the investigation” in the aftermath, without giving details.

Yet charges were dropped because the officers “gradually confessed and repented,” the agency said. [Source]

https://twitter.com/gerryshih/status/812251682985758724

The swift public outrage over Lei’s death was immense, with at least two media directives issued in an effort to contain it. “To his supporters,” Chris Buckley and Adam Wu wrote on Friday, “Mr. Lei symbolized how even middle-class Chinese citizens are vulnerable to abuses of power by unaccountable authority figures. He held a master’s degree from Renmin University in Beijing and worked for an environmental group affiliated with the government, thus standing out from the blue-collar and rural residents who most often accuse the police of brutality.” The case was the latest breakdown of what Weibo user Yuanliuqingnian (@淵流青年) labeled China’s “normal country delusion” after last year’s lethal explosions near Tianjin:

Obviously, if you live in a nice house in Binhai with a BMW and a little dog, in your free time you twiddle your fancy worry beads, or else you go for a run and get your exercise in. You maintain a noble silence on any public incident you’re aware of. On the surface, you look no different from a middle class person in a normal country.

But this is a delusion. One explosion later, and the homeowners in Qihang Jiayuan and Harbor City discovered they’re the same as those petitioners they look down on, making the same moves: kneeling and unfurling banners, going before government officials and saying “we believe in the Party, we believe in the country.” This method has been used by countless petitioners—people from the counties who make five- or six-hundred yuan a month and receive chemical fertilizer subsidies. The homeowners realize, much to their embarrassment, that after an accident there’s really #nodifference between us and them. [Source]

See more on the anxiety of many middle class Chinese in areas from physical safety to education and financial security, via CDT.

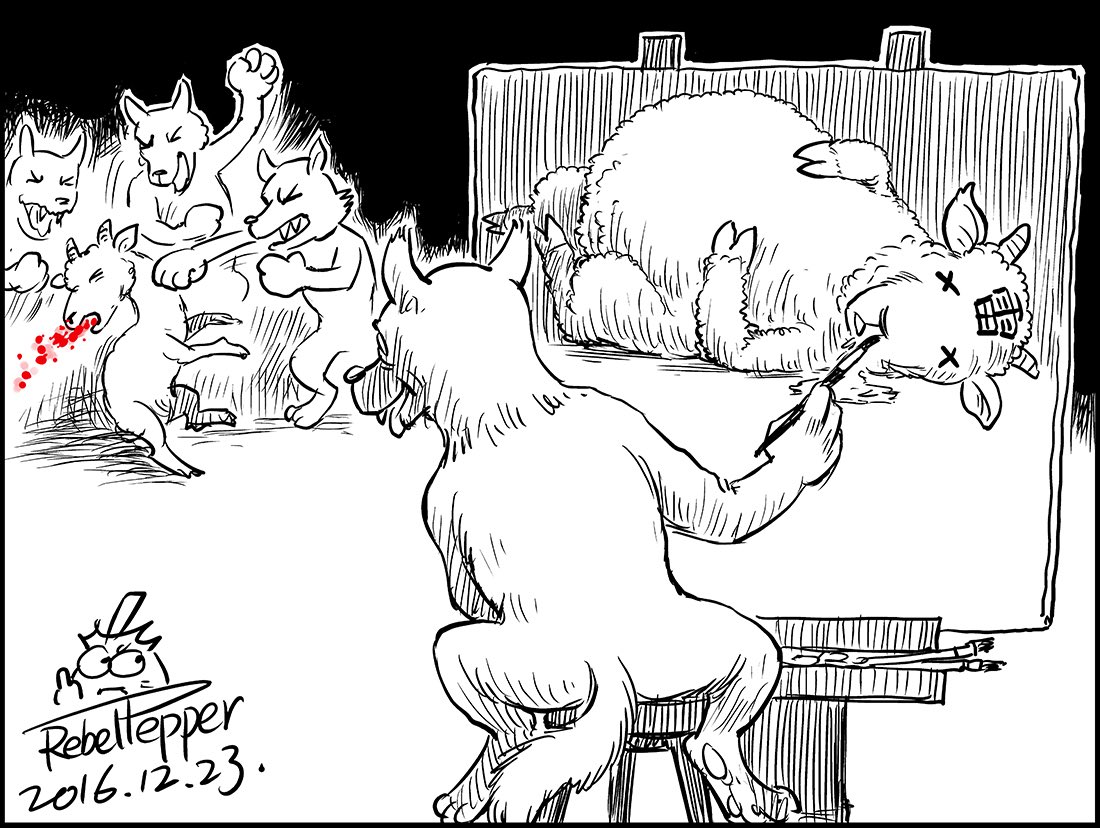

On Twitter, cartoonist Rebel Pepper expressed surprise at the depth of anger the news had unleashed, while highlighting the authorities’ continued downplaying of the violence Lei suffered:

#變態辣椒漫畫 說實話我完全沒想到雷洋案的終極判決會引發這麼大的轟動,微信朋友圈的時間線上全是討論雷洋的帖子,甚至一位做移民生意的朋友説今晚怎麼啦?諮詢移民的客戶突然暴增。。。對我來說好像完全沒有那種震動感,大概是因為早就沒有任何期待了吧 pic.twitter.com/tCrtOgCAbR

— 变态辣椒RebelPepper (@RebelCartoon) December 23, 2016

To tell the truth, I didn’t at all expect the final verdict in Lei Yang’s case to cause such a stir. But it was all that my friends who were online on Wechat were talking about, to the point that one friend who’s an emigration consultant asked what was going on, because the number of people seeking advice on emigration had suddenly exploded … As for me, it didn’t seem all that earth-shaking, probably because I never expected anything else. [Chinese]

On Sina Weibo, many expressed their feelings using biaoqing (表情)images:

Beidao、xiansheng (@北岛、先生): Be careful when commenting, or you’ll be accused of prostitution.

Beidao、xiansheng (@北岛、先生): I suggest a grand plenary session in these five policemen’s honor .. to award them the title of Distinguished Officers.

“OK, say no more.”Yuantengfei (@袁腾飞): Oh, here’s some mild criminal behavior…

Fengmingshuijiao (@奉命睡觉): So they’re saying it was death by overeating

“You have got to be kidding me”Wangdunka (@王顿咖): The picture says it all

“I, Shizuka Minamoto, also want to hit someone”

Soon after Lei’s death, the central government pledged to rein in abuses of police power, with Public Security Minister Guo Shengkun stressing the need “to educate the whole police force to consciously respect the law, study the law and abide by the law.” Public consultation on new rules governing chengguan urban management staff was launched in August, and is ongoing for new revisions to the country’s Police Law. But Human Rights Watch warned this week that the current draft changes to the latter “do little to make the police more accountable, and actually expand the force’s powers in ways that could exacerbate abuses.” From HRW’s submission to the National People’s Congress Standing Committee:

Human Rights Watch has for very many years documented police abuses, including use of torture against criminal suspects, surveillance of ordinary citizens, and unnecessary or excessive force to break up peaceful protests, as well as the harassment and arbitrary detention of individuals and group members who peacefully criticize the authorities or advocate for policy changes. Procurators and judges rarely question or challenge police conduct, and internal oversight mechanisms remain weak. The extraordinary power of the police is reflected in their enormous power over the justice system and the pervasive lack of accountability for police abuse.

[…] Human Rights Watch notes that in recent years incidents of police abuse such as the Qing’an police shooting, the death in custody of environmentalist Lei Yang, and the abusive behavior caught on tape of an officer checking the identity cards of two Shenzhen shoppers, have generated strong public criticism of the police force in China. The proposed revisions to the Police Law serve as an important opportunity to address those criticisms, and to make reforms that bring the law into conformity with international standards. [Source]

See background and a leaked media directive on the Qing’an case; video of the incident in Shenzhen; and more coverage of Lei’s case in English, with much more in Chinese, via CDT.