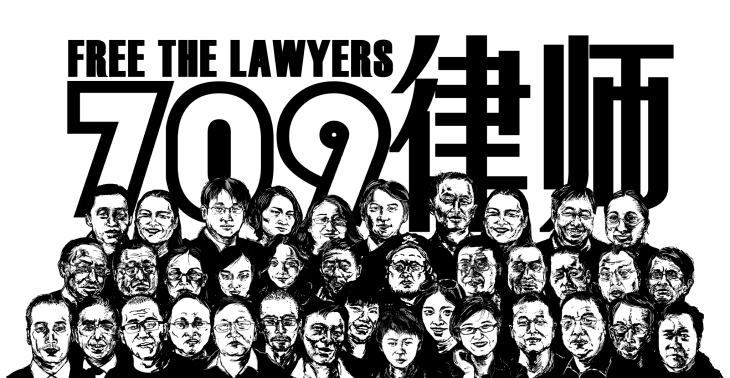

China Change, together with a number of other organizers, will hold an inaugural “China Human Rights Lawyers’ Day” on July 9th in Washington D.C. (with concurrent events planned in Taipei and Hong Kong) to mark the second anniversary of a nationwide crackdown on rights lawyers and activists known as the “709″ or “Black Friday” roundup.

The persecution of rights lawyers in China reached its peak on July 9, 2015, when hundreds were detained and interrogated; the crackdown is now known as the “709 Incident.” The barbarism, cruelty, and absurdity with which the Chinese Communist Party began persecuting 709 lawyers and activists, and the torture and humiliation they suffered, has shocked the world. The 709 lawyers’ own defense attorneys and supporters have put up courageous resistance. The unyielding support and advocacy by the wives of human rights lawyers, through smiles and tears, have become iconic images.

The 709 Incident isn’t over, yet it has already left a profound mark on the development of Chinese civilization. It’s far reaching political and historical significance will become clearer in time.

The date of July 9 must become one that we remember and mark from now on. For this reason, we call for the establishment of July 9 as “China Human Rights Lawyers’ Day.” To inaugurate the occasion we will hold an event in Washington, D.C. to celebrate the bravery, wisdom, and will to resist exhibited by human rights lawyers in China. We’ll recall their suffering and sacrifices, demand accountability for the crimes committed against them, whether by the regime or individuals, and call for the international community to continue monitoring their plight and advocating on their behalf. [Source]

Of the large number of lawyers detained as a part of the crackdown, a number them were formally charged and several others were paraded on state television making alleged confessions. Some of the accused have been given jail terms for the crime of subversion while others have now been freed. Most recently, lawyer Li Heping was released from prison in May with a suspended sentence for subverting state power. Another lawyer released around the same time was Xie Yang, who was tried in Changsha in May before being subsequently freed on bail prior to the announcement of a verdict. Little information is available on those who remain in detention, many of whom have been prohibited from contacting their loved ones. Nothing has been heard from lawyer Wang Quanzhang since he was detained by authorities in August 2015.

Families of the detained rights lawyers have continued to speak out. The wives of the detained lawyers have fought on and resisted attempts by authorities to silence them. Human Rights Watch recounts the plight of some of these lawyers two years on:

On May 19, 2015, police detained activist Wu Gan when he was protesting outside of a court in Jiangxi province over a rape and murder case in which the defense was denied access to court documents. Two months later, the prosecutors’ office in Fujian province, where Wu is from, charged him with “subversion of state power” and “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” In August 2015, Wu was forced to participate in a TV interview with the state broadcaster CCTV in which he was ordered to confess his guilt, but Wu refused to follow the script, according to a complaint filed by his lawyer. Wu also said the police did not allow him to sleep for several days and nights. Wu’s father, Xu Xiaoshun, had been held by the Fujian authorities for 19 months from 2015 to 2017 on charges of embezzlement in a case believed to be retaliation for his son’s activism.

Beijing-based human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong went missing in November 2016 en route home from Changsha, Hunan province. He was later charged with subversion. In March 2017, Jiang appeared on state TV to “confess” that he fabricated the accounts of torture of another lawyer, Xie Yang, to “smear the Chinese government.” In June the Beijing police claimed that Jiang had dismissed the lawyers his family appointed for him, an action his family believed was forced by the authorities.

In August 2016, a court in Tianjin sentenced human rights lawyer Zhou Shifeng and democracy activist Hu Shigen to seven years and seven-and-a-half years in prison respectively after convicting them of subversion. Both men appeared on TV confessing to their “crimes.” In March 2017, Chief Justice of China’s Supreme Court Zhou Qiang, citing the case of Zhou Shifeng, stated that the convictions of human rights lawyers were one of the country’s biggest legal achievements in the past year. [Source]

Those who have been released continue to be closely monitored. Rights lawyer Wang Yu, along with her husband and teenage son, has remained under constant surveillance since Wang’s release on bail last August, after being held for more than a year on subversion charges. Wang’s son Bao Zhuoxuan was detained in Myanmar in 2015 while attempting to travel to the United States. He has now been given a travel ban and prohibited from attending school in Beijing. Ding Wenqi at RFA reports:

Two years after police launched a nationwide operation targeting lawyers, Wang Yu and her husband and colleague Bao Longjun are now living in the northern region of Inner Mongolia along with their son Bao Zhuoxuan, and are seldom seen or contacted by friends or former colleagues.

[…] “They are still not free,” fellow rights lawyer Wen Donghai, who has met with Wang since her “release,” told RFA. “There is even surveillance in their bedroom, and there is a team of people watching them around the clock.”

[…] “According to the rules, their bail period should be up on July 22, after which the authorities should unconditionally drop the charges against them,” he said. “They should regain their freedom in the next couple of weeks, but it doesn’t look as if that’s what the authorities are getting ready to do.”

[…] Meanwhile, others who were granted “bail,” including legal assistant Zhao Wei, have also remained under surveillance, and haven’t been in touch with their usual social circle since leaving the detention center. [Source]

Both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have called on the Chinese government to end its crackdown on rights lawyers and activists.

On the Sinica podcast, Jerome A. Cohen, professor of law at New York University and a leading scholar of China’s legal system, joins Kaiser Kuo and Jeremy Goldkorn to discuss the development of the rule of law in China and the influence that Confucianist and legalist traditions have played in the ongoing crackdown on rights lawyers.

It goes back to the debate between the Confucianists and the legalists. The Han Dynasty that came in for the first time in the 3rd century BC found some way to reconcile Confucianist values and legalist values. The Confucianists believed in what became known as feudal hierarchical values–a father has to behave like a father, a son behaves like a son, a wife like a wife, and their relations are regulated in humane and predictable ways.

The legalists were different. The legalists believed you have to run the society through a harsh rule by law. You had to use law as an instrument of what we today would call authoritarian power to get people to do the right thing. You didn’t try to improve their thinking. You try to stimulate their desire to avoid punishment. Legalism really was an instrument of control that was unattractive to many people. But in the Han Dynasty and thereafter it blended with Confucianism because the rulers of China saw, from their point of view, that you had to use a harsh legal system with no real protections for individuals. But you can do it to enforce Confucian values so that your legal system would reflect Confucian philosophy, and you would punish a son who attacked his father or revealed his father’s crimes differently from the way you punish a father who handled a similar problem with his son.

This has endured. Of course today’s government in China is the heir to this authoritarian tradition. As I think about the current campaign to exterminate human rights lawyers, sometimes physically to destroy them, I think back to how this is consistent with the Chinese tradition. Xi Jinping sometimes in an attempt to find a new value system for the Chinese people to replace the communist values that nobody pays that much attention to and to replace the Western values, the universal values of constitutionalism and judicial independence etc., […has] occasionally resurrected Confucius.

Allegations of torture and other ill treatment suffered by the lawyers have raised questions about Xi Jinping’s promise to build rule of law in the country. According to David Gitter at The Diplomat, the Chinese government at once recognizes the importance of a strong legal system but also deeply fears the political challenge posed by lawyers and a system that is truly governed by a rule of law.

On June 8, the “Hundred Jurists and Hundred Lectures” (百名法学家百场报告会) event on rule of law propagation, known as the “Double Hundred” meeting, took place at the Great Hall of the People in China’s capital. It was there that the Supreme People’s Court Deputy Secretary Jiang Bixin delivered an address on “Implementing the Rule of Law for Guaranteeing the Five Development Concepts.” Jiang explained that economic and social development cannot take place in the absence of the rule of law, and further stated that the current problems arising in China’s development are directly linked to the rule of law’s incomplete development.

[…] However, it has been difficult for China’s leadership to fully contain the rule of law—and those that advocate for it—to areas that don’t challenge the CCP’s monopoly on politics. For that reason, on June 14, the General Office of the CCP and its counterpart in the State Council published their “opinions” on deepening the reform of China’s lawyer system (关于深化律师制度改革的意见). The need to reform the system stems from its current perceived faults, which in the government’s eyes have allowed the nation’s human rights lawyers to dare to challenge the state in the defense of their clients both in the court of law and public opinion arenas. In order to strengthen the “correct” political orientation of the country’s attorneys, the opinions called for Party committees at all levels of government to pursue reforms that include: altering professional standards to regulate lawyers’ behavior, enforcing disciplinary measures that include penalties for firms that violate behavior standards, and targeting lawyers with propaganda to create a “positive atmosphere” for industry reform. [Source]

At China Change, Wen Donghai, who was among the hundreds of individuals caught up in the 2015 crackdown and who later served as Wang Yu’s defense lawyer, reflects on what it means to be a human rights lawyer in China.

Although there’s often a great deal of disagreement in the Chinese legal field about how to categorize a human rights lawyer, there is simply no doubt that 709 lawyers are the true heirs to this title. Their efforts give real meaning to to the vocation of a human rights lawyer, and their comportment in the face of power shows the strength of character of those in their field. Because of the 709 lawyers, China’s human rights lawyers now have clear values to pursue.

With this understanding in mind, I begin to imagine that, in the years to come, there won’t be such a thing in China as a “human rights lawyer,” because as soon as the values pursued by human rights lawyers are internalized by China’s legal community as the universal standard of professional conduct, every lawyer will have become a human rights lawyer. The only distinction will be whether or not a lawyer has the fortune of coming across a case in which rights must be safeguarded, and whether they discharge their responsibility to see it to the end.

Human rights lawyers are guardians of fairness and justice. Their success in this role comes for their proactive involvement in public affairs and the positive leadership role they play. Some people have said that lawyers are manufacturers of public incidents — but I disagree. Public incidents don’t need lawyers to manufacture them; they arise naturally in society. The key is that lawyers can get involved in public affairs, and through their professional activities, knowledge, and experience, to a certain extent guide public discussions. Or to put it another way, lawyers are creators of public discourse — but they don’t manufacture public incidents. It’s precisely through participating in matters of public interest that they’re able to guide the discourse, and thus truly safeguard fairness and justice. [Source]

The values and freedoms that China’s rights lawyers have long upheld are the source of the government’s fear of the country’s legal professionals, writes Terry Halliday, co-director of the American Bar Foundation’s Center on Law and Globalization, at The Wall Street Journal:

What Beijing fears most are the ideals championed by these activist lawyers and the voice they can give to disempowered citizens. Activist lawyers fight for basic legal freedoms. They demand procedural protections for their clients, such as the freedom to choose or meet with a lawyer, the protection of clients from coerced confessions, and standards of fairness in court, including the examination and cross-examination of evidence. They want fair trials and neutral judges. As one lawyer said, “I hate unfairness.”

These lawyers seek an open political society where there is freedom of speech and association, including the ability of lawyers to form bar associations independent of state control. Many leading activists are Christians; they press for freedom of religion and protections for all believers, including the brutally repressed adherents of Falun Gong. They want open exchanges of views and beliefs, where citizens are freed from stifling censorship.

Perhaps most dangerously for a one-party state, activist lawyers want political power to be divided. They insist that the executive be restrained by the other branches of government, especially the judiciary. They want political influence taken out of the courts, with many calling for the abolition of the Party’s Political-Legal Committee, the ultimate decider in sensitive cases.

In short, China fears freedom. Its leaders know that in many former dictatorships, including South Korea and Taiwan, lawyers led the march toward basic legal and political freedoms. China fears potential lawyer-leaders and the substantial proportion of its citizens who want those lawyers to be their spokespersons. [Source]

In the Made In China quarterly, Fu Hualing, Professor of Law at the University of Hong Kong, discusses the future prospect of legal activism in China and the role that human rights lawyers can play in shaping public opinion and influencing political change through case-focused and law-centred mobilization.

Activist lawyers have offered two answers to the challenges. A ‘weak’ answer relies on remedial justice. That is, while well aware of the structural constraints placed on sociolegal activism, lawyers can still choose to do whatever they are allowed to do in order to make a contribution. As long as there is space—no matter how limited this space is— and as long as there are cases—no matter how petty they are—lawyers will continue.

A ‘strong’ answer points to the fact that public interest law survives a brutal political repression thanks to the resilience and strength of a rebellious sector in the legal profession and in civil society. Public interest litigation is not mainly about winning a case, but is about persuading power holders and educating the general public. Education and persuasion are necessarily slow paced and incremental in their processes. In addition, cases and the battles surrounding them serve as boosters for all stakeholders in the rights complex as, one by one, they strengthen the resolve of the forces of civil society and enhance their capacity in their on-going negotiations with the Party-state.

More specifically and pointedly, individual cases do trigger systemic or structural changes. There are many examples of casedriven changes that have happened in the past. While one can argue that legal advocacy in authoritarian states cannot lead to transformative political change—and that, as some human rights lawyers insist, legal battles in court rooms do not have a democratisation potential—one can argue with equal force that, as long as the regime embraces a degree of legality and promulgates laws to protect a range of legal rights, those rights-friendly laws can be enforced more or less effectively, and rights can be protected more or less rigorously. Legal and political opportunities are there, and it depends on civic leaders, professionals, and civil society at large to seize the opportunities to empower their human agency and to maximise their rights and freedoms through socio-legal action. [Source]