The Shenyang Justice Bureau announced on their website that imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo has died from multiple organ failure after being sent to hospital in June in the late stages of terminal liver cancer. The official CGTN also reported the death, via an AP report, giving a rare acknowledgment from Chinese official media of Liu’s Nobel laureate status:

BREAKING: Chinese judicial bureau says Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo has died. He was 61. (@AP)

— CGTN America (@cgtnamerica) July 13, 2017

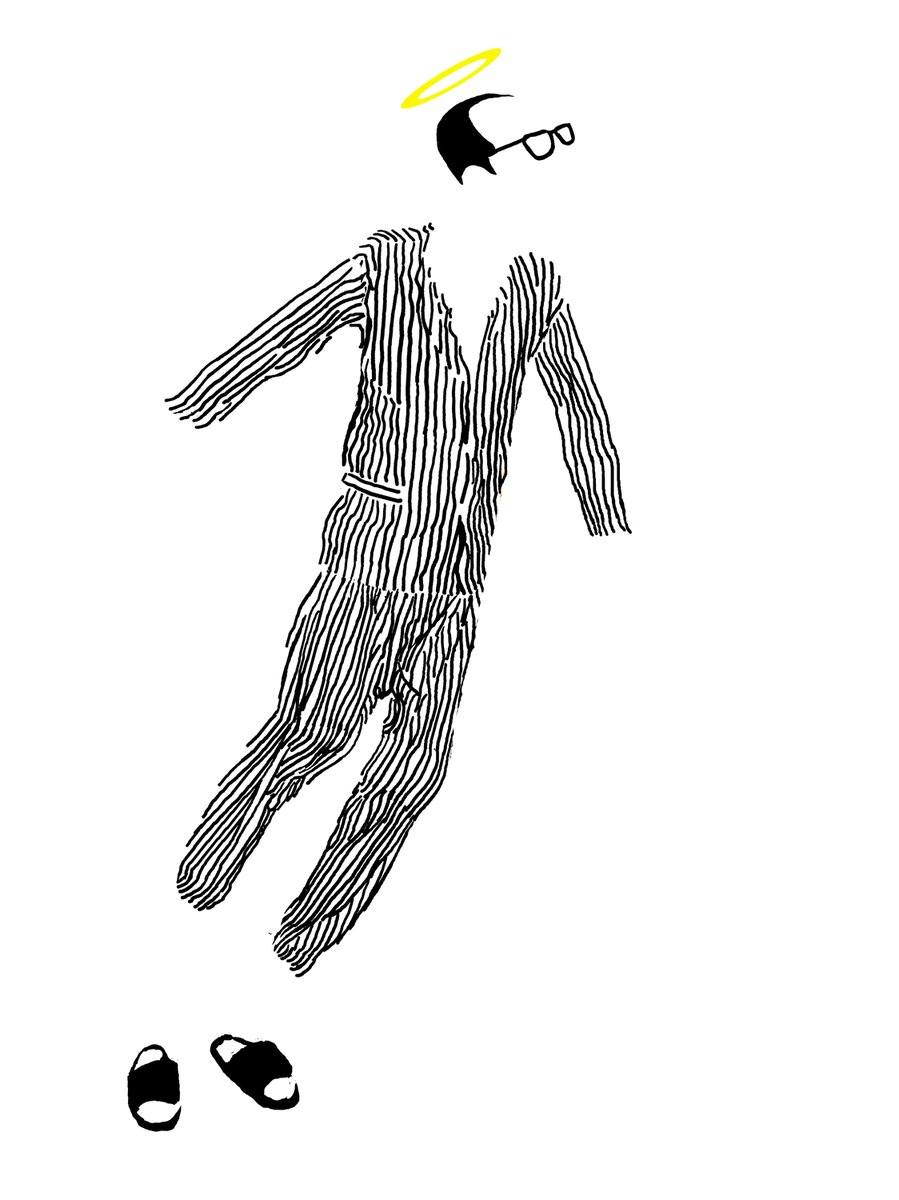

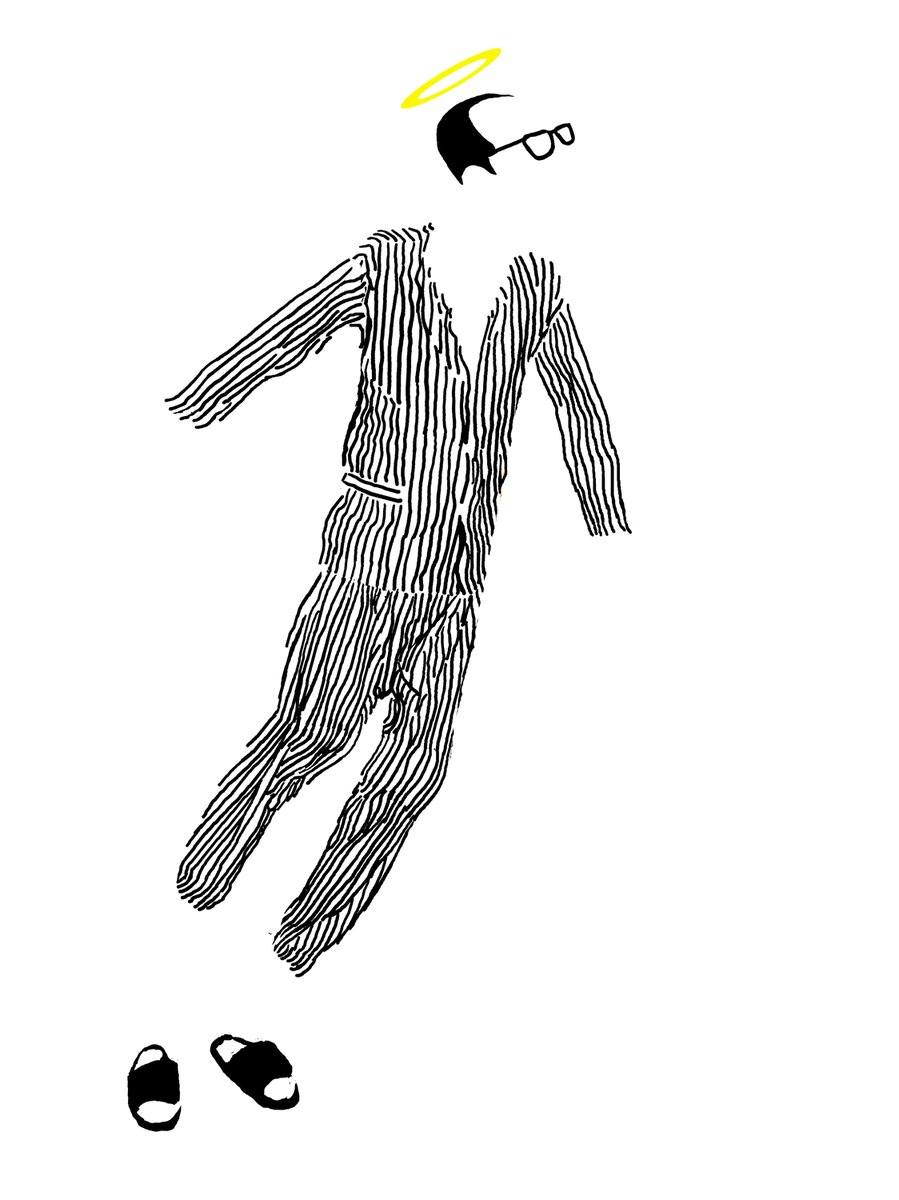

Cartoonist Badiucao honored Liu in a drawing titled, “Final Freedom”:

Liu, age 61, was detained in December 2008, after co-writing Charter 08, a pro-democracy manifesto which was initially signed by more than 2000 people, and eventually by more than 10,000. Charter 08 advocated reforms including an independent judiciary, protection of human rights, separation of powers, freedom of expression and religion, and rural-urban equality. (Read a full translation of the document by Perry Link.) A year later, Liu was sentenced to 11 years in prison on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.” At his sentencing, Liu presented a powerful statement titled “I Have No Enemies,” in which he wrote:

But I still want to tell the regime that deprives me of my freedom, I stand by the belief I expressed twenty years ago in my “June Second hunger strike declaration”— I have no enemies, and no hatred. None of the police who have monitored, arrested and interrogated me, the prosecutors who prosecuted me, or the judges who sentence me, are my enemies.

[…] For hatred is corrosive of a person’s wisdom and conscience; the mentality of enmity can poison a nation’s spirit, instigate brutal life and death struggles, destroy a society’s tolerance and humanity, and block a nation’s progress to freedom and democracy. I hope therefore to be able to transcend my personal vicissitudes in understanding the development of the state and changes in society, to counter the hostility of the regime with the best of intentions, and defuse hate with love. [Source]

In 2010, Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for “his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” Still imprisoned, Liu was not able to attend the ceremony and so was represented by an empty chair, the image of which soon became a meme among Chinese netizens and was subsequently censored.

Liu was a lecturer at Beijing Normal University in 1989 when, as a visiting scholar at Columbia University in New York, he returned to Beijing to participate in the student protest movement. He served as a mentor to the student leaders, and later encouraged students to leave Tiananmen Square as the military approached, which helped prevent many more deaths in the subsequent June 4 crackdown.

In an article announcing his death, Chris Buckley of The New York Times writes about his actions in 1989:

Mr. Liu’s sympathy for the students was not unreserved; he eventually urged them to leave Tiananmen Square and return to their campuses. As signs grew that the Communist Party leadership would use force to end the protests, Mr. Liu and three friends, including the singer Hou Dejian, held a hunger strike on the square to show solidarity with the students, even as they advised them to leave.

“If we don’t join the students in the square and face the same kind of danger, then we don’t have any right to speak,” Mr. Hou quoted Mr. Liu as saying.

When the army moved in, hundreds of protesters died in the gunfire and the chaos on roads leading to Tiananmen Square. But without Mr. Liu and his friends, the bloodshed might have been worse. On the night of June 3, they stayed in the square with thousands of students as tanks, armored vehicles and soldiers closed in.

Mr. Liu and his friends negotiated with the troops to create a safe passage for the remaining protesters to leave the square, and he coaxed the students to flee without a final showdown. [Source]

Carrie Gracie writes for the BBC how the Chinese government fought to erase Liu’s influence from Chinese society, even in his final days, when they refused to grant his wish to travel and die abroad:

Selective amnesia is state policy in China and from Liu Xiaobo’s imprisonment until his death, the government worked hard to erase his memory. To make it hard for family and friends to visit, he was jailed nearly 400 miles from home. His wife Liu Xia was shrouded in surveillance so suffocating that she gradually fell victim to mental and physical ill health. Beijing punished the Norwegian government to the point where Oslo now shrinks from comment on Chinese human rights or Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel prize.

But in death as in life, Liu Xiaobo has refused to be erased. The video footage of the dying man which China released outside the country was clearly intended to prove to the world that everything was done to give him a comfortable death. The unintended consequence is to make him a martyr for China’s downtrodden democracy movement and to deliver a new parallel with the Nobel Peace Prize of 1930s Germany. [Source]

https://twitter.com/tomphillipsin/status/885532951307575296

The propaganda organs in China have worked to restrict coverage of his work, his imprisonment, and his final health status, especially after he was released to a hospital on medical parole in June. As a result, his name and even his Nobel Prize, are not common knowledge for many in China. However, netizens have found ways to pay tribute to Liu and his work online despite the censorship, according to an article from Reuters:

While China’s censorship makes it difficult to assess Liu’s support, he is a “hero” for many liberals in China, even if few will speak out for him, a Chinese editor at an online publication said, declining to be named.

“I am really not sure if it’s accurate to claim he is unknown to the public, (or if) people are just too scared to show their knowledge (of Liu),” the editor said.

Despite the restrictions, internet posters have written in support of Liu and his cause, using variations on his name to avoid the censors.

“When it comes to freedom, comes to constitutional government, we have talked too much, now we need to act,” read one comment on the micro-blogging platform Weibo. “Situations like Liu Xiaobo’s are still a worry, but we nevertheless need people to act, bravely face the risk of death and act.” [Source]

Tom Phillips reports for The Guardian about the immediate response to Liu’s death from his supporters:

News of Liu’s death sparked an immediate outpouring of grief and rage. His peaceful activism and biting criticism of one-party rule meant he had spent almost a quarter of his life behind bars.

“It is so hard. I don’t know if I can say anything,” said the author and activist Tienchi Martin-Liao, a longtime friend, breaking down in tears as she learned of Liu’s death.

“I hate this government … I am furious and lots of people share my feeling. It is not only sadness – it is fury. How can a regime treat a person like Liu Xiaobo like this? I don’t have the words to describe it.“This is unbearable. This will go down in history. No-one should forgot what this government and the Xi Jinping administration has done. It is unforgivable. It is really unforgivable.

“Liu Xiaobo is immortal, no matter whether he is alive or dead,” said Hu Ping, a friend of almost three decades who edits a pro-democracy journal called the Beijing Spring. “Liu Xiaobo is a man of greatness, a saint.” [Source]

While German Chancellor Angela Merkel and representatives of the Trump administration had called for more lenient treatment of Liu, human rights activists and others criticized foreign governments for not speaking up more forcefully in defense of Liu. An op-ed on The Economist outlines their reasons why Western governments should have supported Liu:

A vital principle is at stake, too. In recent years there has been much debate in China about whether values are universal or culturally specific. Keeping quiet about Mr Liu signalled that the West tacitly agrees with Mr Xi—that there are no overarching values and the West thus has no right to comment on China’s or how they are applied. This message not only undermines the cause of liberals in China, it also helps Mr Xi cover up a flaw in his argument. China, like Western countries, is a signatory to the UN’s Universal Declaration, which says: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” If the West is too selfish and cynical to put any store by universal values when they are flouted in China, it risks eroding them across the world and, ultimately, at home too.

The West should have spoken up for Mr Liu. He represented the best kind of dissent in China. The blueprint for democracy, known as Charter 08, which landed him in prison, was clear in its demands: for an end to one-party rule and for genuine freedoms. Mr Liu’s aim was not to trigger upheaval, but to encourage peaceful discussion. He briefly succeeded. Hundreds of people, including prominent intellectuals, had signed the charter by the time Mr Liu was hauled away to his cell. Since then, the Communist Party’s censors and goons have stifled debate. The West must stop doing their work for them. Mr Liu’s work is, sadly, done. [Source]

Read statements from Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International about Liu’s death. Supporters also mourned him in Hong Kong and on Twitter:

More than a hundred people line up at a late-night vigil in Hong Kong to leave flowers and their signatures to mourn Liu Xiaobo pic.twitter.com/jbv5vOLVXl

— Alan Wong (@alanwongw) July 13, 2017

Liuxiaobo has died. His love, courage and strength will never die. #liuxiaobo #刘晓波

— Teng Biao (@tengbiao) July 13, 2017

Opened up Weibo and wow, the censors really can't keep up with the #LiuXiaobo news. Lots of posts, albeit slowly disappearing.

— jlewr.bsky.social | Joseph LR | 羅瑞哲 (@jlewr) July 13, 2017

https://twitter.com/niubi/status/885517919823835136

https://twitter.com/niubi/status/885535919461343233

Chinese censorship of Liu’s death has gone crazy tonight. Even “RIP” is not allowed to be posted on Sina Weibo. pic.twitter.com/WarKkLVQ0o

— Adam_Wu (@Adam_WuTong) July 13, 2017

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on #liuxiaobo: he was a "true embodiment of the democratic, non-violent ideals" pic.twitter.com/KLJGVz9fRE

— Maya Wang 王松蓮 (@wang_maya) July 13, 2017

When I interviewed #LiuXiaobo on 7-4-05, he said he thought he'd see democracy in China in his lifetime. His death is tragic. Rest in peace.

— MaryKay Magistad (@MaryKayMagistad) July 13, 2017

https://twitter.com/TJMa_beijing/status/885509393118253056

An online public memorial day and permanent online memorial hall are being planned for Liu Xiaobo https://t.co/BVMvuY4Pfr

— GreatFire.org (@GreatFireChina) July 13, 2017

https://twitter.com/kemc/status/885524035760553984

In Twitter, Lotus Ruan is collecting examples of censorship of Weibo and WeChat posts related to Liu.

Liu’s wife, poet Liu Xia, has been held under house arrest since his detention and has suffered from ill health and depression as a result. Tom Phillips wrote about the couple’s close bond in a Guardian article just before Liu died. Amnesty has launched a petition calling for an end to her house arrest and surveillance.

Liu Xiaobo's last words were goodbyes to Liu Xia, his wife. He wished her to live a good life (好好生活), doctor recalls https://t.co/qBOaiJVei9

— Alan Wong (@alanwongw) July 13, 2017

'Even if I am crushed into powder, I will embrace you with ashes': #LiuXiaobo to #LiuXia. Sole goal now: freeing her. pic.twitter.com/QLULE8K7zX

— Sophie Richardson (@SophieDRich) July 13, 2017

Liu Xia is a talented photographer. Some beautiful shots of her husband before he went to prison. #LiuXiaobo pic.twitter.com/hJmKOUvNGc

— Jon Kaiman (@JRKaiman) July 13, 2017

Read 13 years of coverage of Liu Xiaobo, Liu Xia, and Charter 08, via CDT. See also tributes to Liu by his friends and colleagues, Geremie R. Barmé in China Heritage, human rights activist Li Xiaorong in The New York Times, University of California Riverside’s Perry Link in the New York Review of Books, and 1989 student leader Wu’er Kaixi on Medium. A video obituary from the Wall Street Journal includes old footage of Liu.