The 1998 suicide of Peking University student Gao Yan after her alleged rape by a professor has become, according to The New York Times, "a rallying cry for China’s fledgling #MeToo movement, inspiring calls for the government to do more to prevent sexual assault and harassment." Over the past two weeks, a second scandal has emerged over the university’s response to freedom of information requests by current students seeking school records about Gao’s case. One of them, Yue Xin, wrote in an open letter (translated by CDT) that she and her family had been harassed and intimidated by university authorities in a series of "interviews." These culminated in a visit from a teacher accompanied by her mother in the early hours of April 23, and in her temporary departure from the university. In the letter, Yue demanded an apology, legal explanation, and an end to any further interference. The letter prompted a wave of support including a commentary in the Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, but also a heavy-handed response including restrictions on other media coverage, intense social media censorship, and heightened surveillance on campus.

In a new essay dated April 30, under her pen name Mu Tian, Yue once again thanked her supporters and lamented the pressure under which some had come. She described the "interview" in the early morning of April 23 in greater detail, and pointed out alleged inaccuracies in the school’s version of events. Finally, she explained how the emotional struggles of the past week have heightened her resolve to follow the sense of social responsibility previously described in a February essay on social inequality and access to education, translated by CDT. Once again, Yue argued that those who share her privileged background owe a debt of solidarity to those less fortunate, including gōngyǒu 工友, or "worker friends"—a term sometimes used by self-identified Marxists.

CDT has translated the April 30 essay. (Read the full text here.) Its introduction, conclusion, and other highlights are excerpted below:

Mu Tian: On the week since my open letter (originally published on the public account "M. Mu Tian’s Pickaxe")

Dearest friends, whether I’ve met you yet or not:

I’ve carefully read all the essays you’ve published over the past week, every comment on WeChat, Weibo, Zhihu, or Facebook. I’ve read every character of the thousands upon thousands of private messages to my public WeChat account. The bread, pears, ugli fruit, pineapples, blueberries, and jackfruit sent by my classmates were so sweet; the note of support my teacher brought me, "hoping you are able to get back to being your normal self," was so warm. Every one of those short-lived, censored essays meant a lot.

A “thank you” can hardly express my gratitude.

Because I know that this kind of concern, assistance, and support all mean bearing burdens, risks, and costs that shouldn’t have to be borne.

A classmate who reposted People’s Daily’s commentary about this matter was forced by his father to delete the post and close his WeChat account.

A worker friend who shared "The Schoolmate Mu Tian That I Know" was hunted down and asked "what are you up to? What have you got planned?" This worker friend stepped forward and said, "the more they tell me not to post, the more I’ll post. If you tell me not to, I’ll do it anyway."

Schoolmate Li Yiming, furthermore, started a petition demanding that school authorities properly repair the damage their interviews have done, strengthen institutional controls, fully guarantee students’ legal rights and interests, and improve mass supervision and restriction mechanisms in the interview system. By now, almost 200 teachers, students, and alumni have signed, and it’s very possible that these people, including Li Yiming herself, have now borne the same kind of interview pressure as myself ….

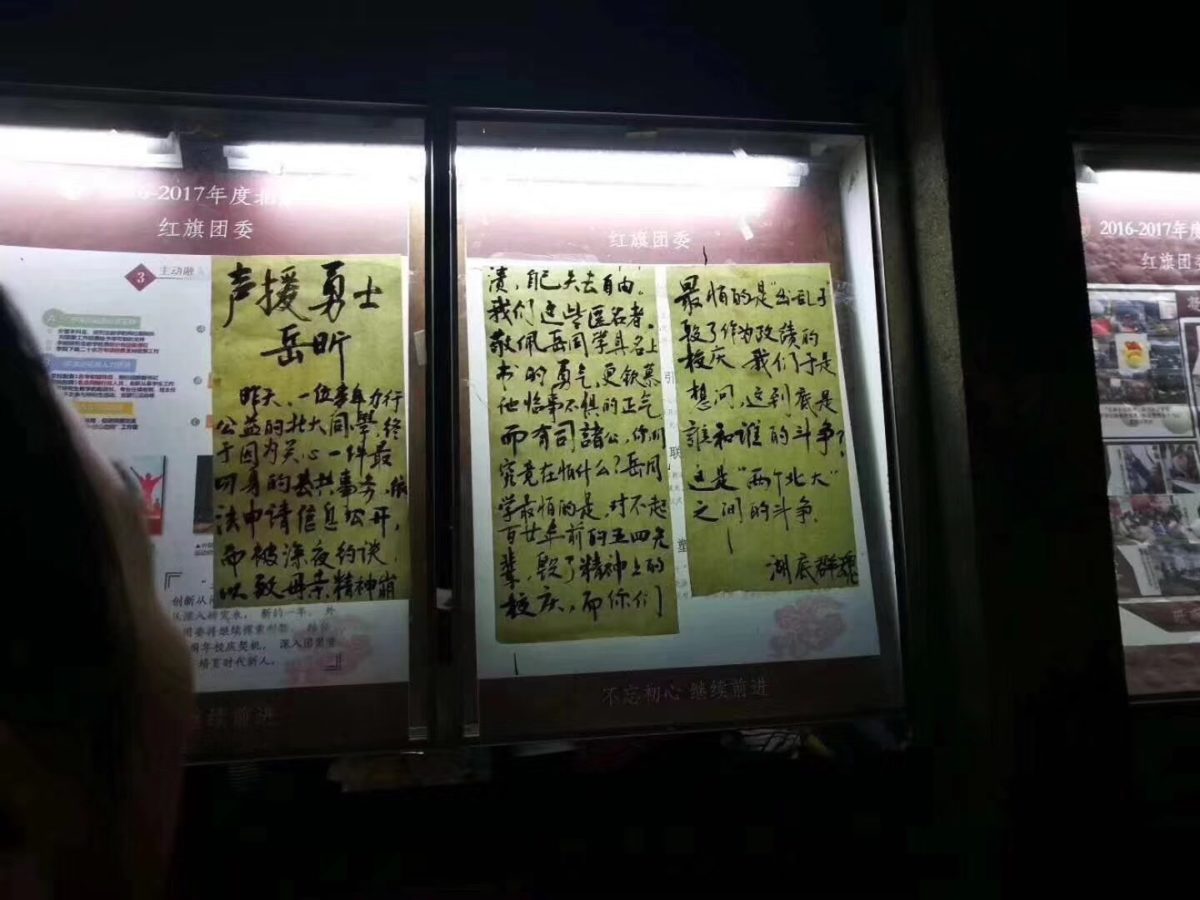

Over the past few days, I’ve been woken at 4 a.m. by dreams in which friends have come under pressure because of their shared articles, signed petitions, blockchain inscriptions, or big-character posters. This anxiety is because I’ve brought trouble on so many friends.

I’m anxious not only for my friends, but also for my family, because I know only too well how anxious they are for me. If anything happens to me, they really might suffer physical and emotional collapse.

On top of the anxiety, I feel frustration.

The frustration isn’t because of the few scattered rumors smearing me: they can’t survive the slightest scrutiny, and the good will out.

Instead it’s because, in the days when I’ve been forced to keep quiet, I had no way to see my friends as before, no way to express my gratitude to each of them in turn, no way to add my own voice on the topic I was sincerely following, no way to lend support when I saw worker friends in my circle courageously resisting. I knew, moreover, that my family’s mood was relaxing day by day, under the premise that I’d been completely silenced and "won’t ever get involved in that kind of situation again."

Before deciding to write this piece, I felt constantly conflicted. I worried that the essay would be like a time bomb, blowing up my family, which had been gradually calming down, and causing a repeat of everything I went through on April 23. I’m afraid that my family might really cut ties with me because of this, or even fall into long-term illness.

Even so, I still feel now a deep need and responsibility to explain to everyone about what really happened that night, how the school’s account of the interview diverges from the facts, the psychological conflicts I’ve gone through over the past week, and why I’ve decided to continue stepping forward.

[…]

Regarding the matter’s subsequent handling, the teacher [on the morning of April 23] thought that I should graduate without incident, and suggested "don’t use your phone or WeChat for now," unless I needed to contact family members, which would be OK. Using the requirement for Peking University teachers to obtain approval from school authorities before accepting interviews as an example, she explained, "you think you can write something, make your voice heard through the media, or post on your own public WeChat account, thinking these are your freedoms? Think again. Let me tell you, kid: you have no real freedoms …. When it comes to you, I think no freedom is best at the moment."

[…]

[…] For the statement that everyone saw with large blank areas, those areas were actually filled with words initially.

The complete statement was:

Heartfelt thanks to everyone who offered me their concern and help, I would like to return my highest respects to all of you!

I have returned to campus.

At this juncture, we need to remain even more calm and rational, united as one, and continue to promote a freedom of information mechanism, anti-sexual harassment mechanism, improved interview mechanism, and protections of students’ fundamental rights at the substantial and procedural levels.

This was my intention from the beginning, for all of us to see:

When participating in campus affairs, keep matters out in the open, do not mince words. This is not to push certain students or teachers towards the heart of the struggle, but to promote a real solution on a systemic level;

More and more students are coming forward despite the pressure of potential interviews, not for self-promotion, but so their basic rights are not infringed upon, so that more students can participate in campus affairs by their own initiative and not be suppressed.

We are all seeds. United and working in concert, inevitably we will break through and flower.

On Wednesday April 25, three family members flagged me down at the entrance to my dorm building, requesting that I leave only two sentences in the statement: “I’ve already returned to school and resumed classes, thank you all.” […]

[…]

[…] Why I Decided to Continue Standing Up

To be honest, the reason I now continue to give voice, compared with my initial reason, has also changed.

The most direct reason for my open letter was definitely the impact on myself and my family. I thought that it could help to safeguard my personal rights, make the school give the actual truth, and restore the relations between myself and my family. But, I soon learned that if it were only for myself and my family, I would have quickly cowered in compromise.

Admittedly, I heard that some school official said at a certain department’s meeting that my character wasn’t good, that I had a psychological issue arising from family misfortune; but I know, I’m not afraid of my own slanted shadow, if there were someone who thought that way, they should say so under their own name, and say it out frankly.

Now, if I don’t continue, if I no longer care about “similar rights defense related affairs,” the teacher probably won’t come looking for me, my family’s attitude towards me will likely return to normal, and I’d again be able to enjoy the happiness and warmth provided to Beijing’s middle class—a comfort like the white petals of the early summer hawthorn trees.

But, if that really was the case, the openness and perfection of the freedom of information mechanism, the anti-sexual harassment mechanism, and the interview mechanism would not easily be mentioned; even if we had these so-called mechanisms, they’d likely be the products of closed-door meetings, and ordinary students who wanted to maintain their rights to participate in the formulation, management, and oversight would find it difficult to do so.

I can’t let my junior students continue their fight for their full lawful rights as sullenly as before;

I can’t let the next Gao Yan be compelled to suffer in silence, even at the end of her life.

On Tuesday, April 24, I felt a bit calmer, and was continuously thinking: I am only an ordinary person, doing an ordinary thing, in no way am I a “warrior”, a “hero.” If I was considered a “warrior” or a “hero,” it could only be said that this era and this system is too full of abnormality and irrationality.

At the same time, I also reflected on the fact that as I was writing my self-introduction, I got an unusual amount of attention doing an ordinary thing just because I was a PKU student. At the same time, worker friends who were resisting received much less attention and resources. If I can’t stand with those worker friends, there is no doubt that I have stolen attention and resources that should really belong to them.

That day, I wrote in my diary: “we must cherish all that we have, and even more we must speak for those people who have a hard time being heard.”

I hope I have the capability to defend more people, to help more people, and not the opposite.

I see the pneumoconiosis, I see the work injuries, I see the crane worker friends as they resist.

On Friday, April 27, I was walking down the road, watching the worker friends curled up under a bridge in the hot afternoon.

On Wednesday, April 25, I was eating dinner, a worker friend came and sat next to me. She said she could only secretly sit to rest here as there was no camera in sight, and without that place she would not be allowed to rest.

International Workers’ Day will soon be here; so many workers want to rest, it’s so very hard.

Seeing the worker friends standing together with other worker friends urged me to summon my courage: compared to the situations of these people who are owed wages, worked overtime, without vacation, with injuries and illnesses, and not guaranteed food or clothing, the pressure that I face myself is really not so terrible, and I have no justification to retreat in weakness. Only if we continue to mobilize with courage, to stand up and fight for a better system, only then can we guarantee that our classmates and workmates can stand and exercise their legal rights, only then will they not be hit so disastrously.

From April 23 until now, my WeChat public account “MuTianWuHua” has received 1774 yuan in reward donations. After deducting the 1% service charge, that’s 1756.26 yuan. On behalf of all my friends, I’ll take this donation money and hand it over to all the workers fighting pneumoconiosis, even though it really is an utterly inadequate measure.

Henceforth, I will stand together with the world’s laborers.

Finally, as a PKU graduate, I’ll still have to talk about all the banal old topics: how we should love PKU, about what the spirit of PKU is.

A week ago in the middle of the night as I was interrogated, I was asked twice: “do you wish ill upon PKU?”

I replied: If I wished PKU ill, I wouldn’t be concerned with PKU; whatever happens to PKU I wouldn’t care about, I’d only be concerned with my own affairs.

Love for PKU is not complicated, it is to look after PKU. The spirit of PKU is also very simple, it is to break through the social indifference and isolation, to offer an earnest and positive voice for both the most oppressed and most powerful.

This type of love, this type of spirit, certainly shouldn’t only belong to PKU, or to the people of PKU.

Mu Tian

April 30, 2018 [Chinese]

Josh Rudolph, Sandra Severdia, and Ya Ke Xi also contributed to this translation.