Interpol President Meng Hongwei has resigned from his leadership position at the international police liaison organization, effective immediately. The resignation took place hours after Chinese authorities confirmed that they have detained Meng, who has not otherwise been seen nor heard from since he mysteriously disappeared late last month on a trip home to China from Lyon, France, where he had been living with his family since he took up his Interpol appointment in November 2016. French authorities have launched a probe into Meng’s disappearance after his wife reported him missing on October 4th, with a police enquiry now underway. Meng is a senior Chinese Communist Party member and China’s vice-minister for public security. His elected position at Interpol was not set to end until 2020. Kim Willsher at The Guardian reports:

Interpol said it had received his resignation “with immediate effect” late on Sunday. It was the latest twist in the mystery of Meng’s disappearance last month after he flew from France to China.

[…] On Sunday, a statement from China’s ruling Communist party said Meng was “under the monitoring and investigation” of the new anti-corruption unit, the National Supervision Commission, for suspected serious violations of state law. It gave no further information about the reason for his arrest and detention.

Meng, 64, who is also a senior Chinese security official, had more than 40 years’ experience in criminal justice, particularly in the field of drugs control, counter-terrorism, immigration and border control, before becoming president of Interpol, the international criminal police organisation based in Lyon, in November 2016. He is a senior member of the Communist party. [Source]

Statement by the INTERPOL General Secretariat on the resignation of

Meng Hongwei. pic.twitter.com/c2daKd9N39— INTERPOL (@INTERPOL_HQ) October 7, 2018

Laurie Chen and Catherine Wong at the South China Morning Post cited unnamed sources that Meng is currently under investigation on suspicion of unspecified legal violations, noting that he was “taken away” immediately upon arriving in China.

It is not yet clear why Meng is being investigated or exactly where he is being held.

[…] Under China’s supervision law, a suspect’s family and employer must be notified within 24 hours of a detention, except in cases where doing so would hinder an investigation. It appears Meng’s wife was not informed.

[…] While Meng is listed on the website of China’s Ministry of Public Security as a vice-minister, he lost his seat on its Communist Party Committee, its real decision-making body, in April.

According to his own page on the site, Meng’s last official engagement was on August 23, when he met Lai Chung Han, a second permanent secretary of Singapore. [Source]

China’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection issued a one-line statement over the weekend corroborating the media’s account of the investigation, stating that Meng is on “suspicion of violating the law” and was “under the supervision” of the National Supervisory Commission, China’s new anti-corruption body. It did not elaborate on why Meng is being investigated or where he is being held.

#BREAKING: Meng Hongwei, the vice-minister of public security, is under probe by the National Supervisory Commission for suspected breach of law, the commission said late Sunday. Meng is also president of Interpol. pic.twitter.com/V051WRv71j

— China Daily (@ChinaDaily) October 7, 2018

Although it is yet unclear what Meng is being investigated for, his case resembles the downfall of senior officials when they are suspected of graft, which often begins with removal from key roles within the party. While Meng is still officially listed as China’s vice-minister of public security, AFP journalist Matt Knight notes that Meng has been stripped of his Party Committee membership since April and removed from several other internal leadership positions since late last year.

https://twitter.com/MattCKnight/status/1048189091802624000?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

https://twitter.com/MattCKnight/status/1048247168052543488?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw

If speculations hold true, Meng would be the latest senior official to be caught in President Xi Jinping’s high-profile crackdown on corruption within the Communist Party–one that has targeted more than one million officials at all levels of government and military bodies, from lowly “flies” to powerful “tigers.” Critics have argued that the ongoing campaign is being used as a weapon by Xi to take down political rivals and consolidate his power. Prominent politicians and military generals who have been netted in the anti-graft campaign thus far include former rising political star Sun Zhengcai, security chief Zhou Yongkang, and general Guo Boxiong. China’s minister of public security Zhao Kezhi was cited telling a group of senior police officials in Beijing that Meng was accused of taking bribes, among other crimes. It has also been hinted that Meng’s apparent downfall is likely in some ways connected to Zhou Yongkang. However, those close to Zhou have dismissed the speculation that the two cases are linked, citing that the two men were ‘never close.’

The National Supervisory Commission (NSC) handling Meng’s case is a powerful investigatory body established earlier this year to oversee President Xi’s ongoing anti-corruption efforts. The agency is a strengthened version of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection that functions independently of the courts and is authorized to hold suspects for months at a time without providing legal counsel. The agency operates a new detention system called “liuzhi,” which is likely what Meng is being put through. From Human Rights Watch’s Maya Wang:

This means it’s highly likely that Meng has been subjected to “liuzhi,” a form of secret detention effectively controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. Under liuzhi, detainees are held incommunicado – without access to lawyers or families – for up to six months.

Little is known about the treatment of detainees during liuzhi, because the program and the government agency running it, the National Supervision Commission, are new. In March this year the commission absorbed existing graft-fighting powers vested in other government departments, and was empowered to investigate anyone exercising public authority. It shares space and personnel with the Party’s disciplinary agency, the Central Commission for Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI).

[…] In its effort to give liuzhi a veneer of legality that shuanggui lacked, authorities say interrogations will be videotaped and families notified within 24 hours, among other reforms. But so far, the signs are not promising: in May, a 45-year-old man reportedly died after 26 days in liuzhi, his body covered in bruises.

What’s next for Meng Hongwei? The formula is simple: like others forcibly disappeared before him, including human rights activists mistreated in custody by Meng’s public security ministry, he faces detention until he confesses under duress, an unfair trial, and then harsh imprisonment, possibly for many years. While Meng’s whereabouts remain elusive, his fate is not. [Source]

Beijing stopped short of saying Meng was suspected of “violating party discipline” or that the party’s anti-graft force is involved, as it always does, to make it look like a strictly legal problem with Meng. We all know CCDI and NSC works in the same office. https://t.co/9sSXtAplpt

— Jun Mai (@Junmai1103) October 7, 2018

#MengHonwei has been taken by the #NSC. Likely placed into #Liuzhi, a form of #enforceddisapperance designed based on #RSDL. https://t.co/g3dV9vuoYE

— Safeguard Defenders (@SafeguardDefend) October 7, 2018

For media about to publish anything about #MengHongwei, you really need to read this (or something similar from someone else) before hitting the enter button. https://t.co/VlO7wJkDXQ … @INTERPOL_HQ

— Safeguard Defenders (@SafeguardDefend) October 7, 2018

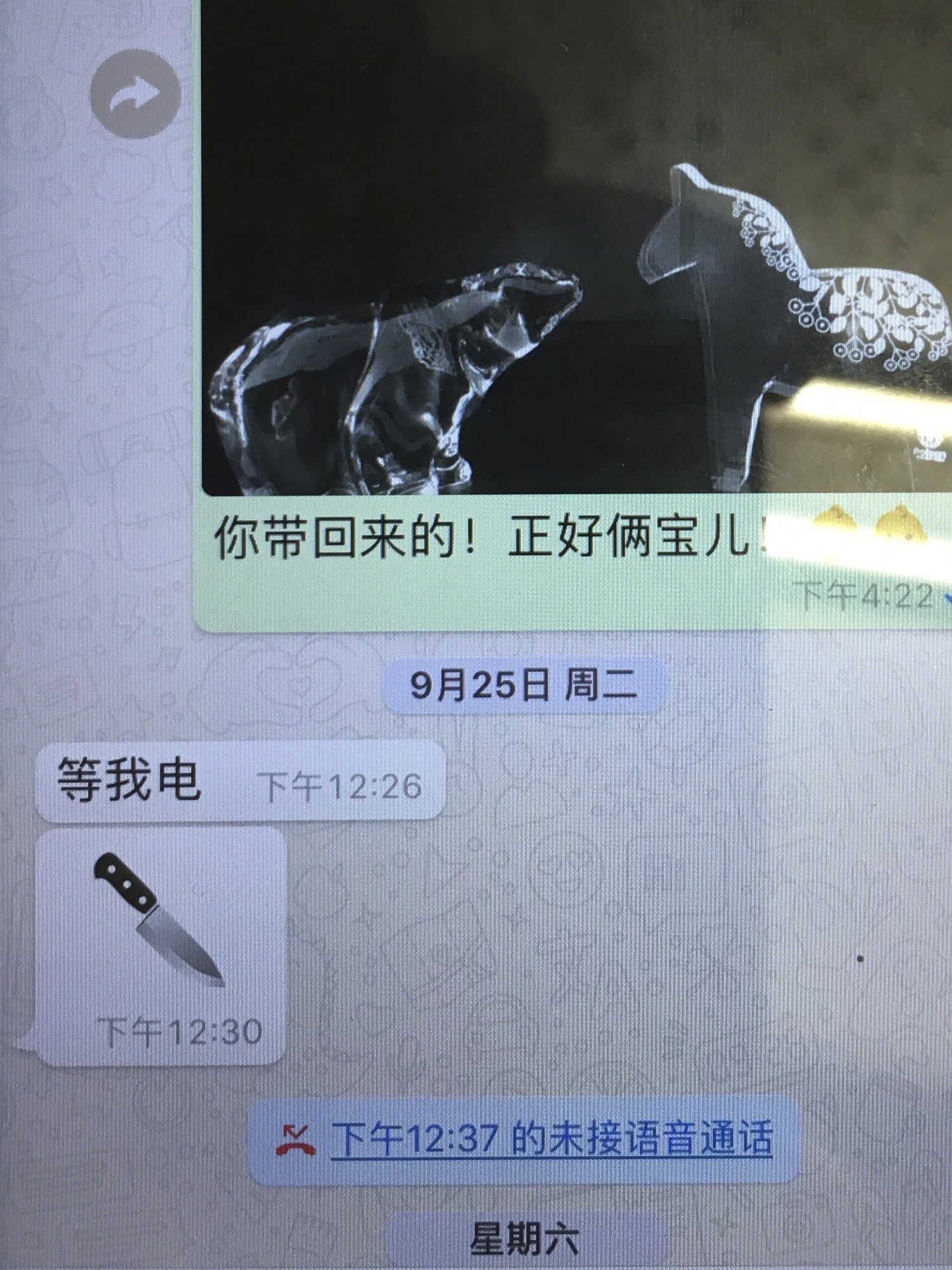

The Chinese government’s announcement of Meng’s detention came shortly after Meng’s wife Grace revealed at a press conference in Lyon that she had received an ominous text message from her husband signalling he was in danger minutes before he disappeared. Citing safety concerns for herself and her children, Mrs. Meng kept her back to reporters while she made an emotional plea for international help in bringing her husband to safety. Her actions were unusual given that family members of disgraced Communist officials almost never make such public appeals. AP’s Gillian Wong and John Leicester report:

Grace Meng said she hadn’t heard from her husband since Sept. 25. Using his Interpol mobile phone, he sent her the emoji image of a kitchen knife that day, four minutes after he sent a message saying, “Wait for my call.”

[…] Of the knife image, she said: “I think he means he is in danger.” She said he was in China when he sent the image.

“This is the last, last message from my husband,” she said. “After that I have no call and he disappeared.”

She said he regularly traveled back and forth between Lyon and China for his job. He had been on a three-country tour, to Norway, Sweden and Serbia, for Interpol before his latest trip back to China, she said. [Source]

In case some wonder what former Interpol chair meant by a knife emoji, a piece I did three months ago on what some Chinese officials go thru in corruption probe and why some don't trust the system https://t.co/sUFk98BOuH via @SCMPNews

— Jun Mai (@Junmai1103) October 8, 2018

Mrs. Meng further revealed that she has been the target of online harassment and death threats. In a separate article, Gillian Wong and John Leicester detail a chilling call Mrs. Meng received from a man allegedly working on behalf of the Chinese government:

“You listen, but you don’t speak,” the man on the other end said. “We’ve come in two work teams, two work teams just for you.”

[…] Speaking to the AP late Monday at a hotel in Lyon, the French city where she lives and Interpol is based. Grace Meng said she had put their two boys to bed when she got the threatening call. It was one week after her last contact with her husband. On Sept, 25, he sent her from China an emoji of a knife — suggesting to her he was in danger.

The man who called her on her mobile phone spoke in Chinese, she said. She said the only clue he gave about his identity was saying that he used to work for Meng, suggesting that the man was part of China’s security apparatus. He also said he knew where she was.

“Just imagine: My husband was missing, my kids were asleep, all my other phones weren’t working, and that was the only call I got. I was so frightened,” she said. [Source]

China’s willingness to risk its international reputation and go after an official with high international standing sets a precedent for how far the Xi administration is willing to go to prioritize domestic politics and Party survival over respect for international norms. Meng’s arrest is expected to undermine China’s legitimacy as it seeks to play a greater role in international affairs, with many now left uncertain whether it remains sensible to continue giving China leadership roles in multilateral organizations. The New York Times’ Edward Wong and Alissa J. Rubin report:

Mr. Meng’s appointment “was considered quite an achievement for China and a sign of its international presence and growing influence,” said Julian Ku, a professor at Hofstra University’s Maurice A. Deane School of Law, who has studied China’s relationship with international law.

While China may have had its eye on placing its citizens in other top posts at prominent global organizations, “the fact that Meng was ‘disappeared’ without any notice to Interpol will undermine this Chinese global outreach effort,” Mr. Ku said. “It is hard to imagine another international organization feeling comfortable placing a Chinese national in charge without feeling nervous that this might happen.”

[…] His detention means that internal party dynamics supersede any concern from the party about international legitimacy or transparency.

The party’s moves in this case “suggest that the domestic considerations outweighed the international ones,” said Mr. Ku, the law professor. “This has always been true for China, but perhaps not so obviously true as in this case.” [Source]

The incident shows that internal party loyalty and obedience is of utmost importance in Xi’s China, irrespective of external pressure. Ben Westcott reports for CNN:

Unusually, the statement released by the Chinese government confirming Meng had been detained under suspicion of corruption didn’t just mention the charges. It also stressed the importance of loyalty to both Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Party’s leadership.

Michael Caster, human rights advocate with Safeguard Defenders, told CNN he found the wording of the Chinese statement “really alarming.”

“I think it’s very concerning (that) China thinks it can abduct and arbitrarily detain the sitting head of an international organization without serious consequences,” said Caster.

“Not only is it pointing out the supposed criminal violation, its … emphasizing that ultimately Meng Hongwei was serving at the discretion of the Communist Party, which is headed by Xi Jinping,” added Caster. [Source]

China Change has compiled a list of key takeaways from Meng’s arrest and how it fits into broader changes taking place in China:

We will refrain from wallowing in the rich irony and absurdity of the event, but there are a few points to register:

- People who hold positions in international organizations, regardless of their position or nationality, should perform their duties as independent individuals, rather than as representatives of their respective countries. But the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) affords none of its members such independence, Meng Hongwei among them. As far as the CCP is concerned, he is the Party’s man above all, and the Party can sanction him at any time as it sees fit, even during his Interpol term.

- It follows that Meng Hongwei, in his capacity as Interpol chief, was inevitably subject to the Party’s directives and control.

- Meng Hongwei’s mafia-style abduction sends a stark message to the international community: totalitarian China does not conform to international procedures and is incapable of participating in world affairs as a normal country.

- Almost exactly a year ago, Xi Jinping attended the 86th Interpol general assembly in Beijing and delivers a keynote speech emphasizing “cooperation, innovation, the rule of law and win-win results and build a universal and secure community of shared future for mankind.” [Source]

Ultimately, the Interpol incident could not only cost China its reputation and aspirations to lead global organizations but also hurt those international institutions themselves as they grapple with the now manifest political complications of appointing Chinese officials. From Adam Minter at Bloomberg:

But the impact of China’s power play will be even more far-reaching. Chinese participation in global organizations isn’t just a status-enhancing honor. It’s a necessity: Solving international problems of all sorts will be harder if the world’s second-largest economy doesn’t play a leading role in addressing them. If global institutions can no longer trust that Chinese domestic politics won’t interfere with their work — and feel secure appointing Chinese to top positions — their legitimacy and effectiveness will inevitably suffer.

Prior to Meng’s detention, the case for greater Chinese influence in such institutions seemed clear-cut. In the space of 40 years, China has evolved from economic, military and cultural afterthought into a juggernaut. As its status has grown, so has the ruling Communist Party’s desire to play a greater role in setting global standards. For years, the World Bank has been a particular focus, with Chinese leaders arguing that the institution’s voting structure didn’t sufficiently recognize China’s economic status or the voices of other developing countries. In 2016, the World Bank signaled its agreement by appointing Yang Shaolin, a Chinese national, to be its second-in-command.

[…] Yet by abducting him without any notice to Interpol (much less a public accounting of charges), China has clearly demonstrated its lack of respect for international standards of governance. The damage will be lasting. Global organizations will be understandably wary of putting another Chinese into a leadership position, and the Chinese government — rarely willing to admit a wrong — is unlikely to offer assurances that it will respect international norms in the future. That’s a setback for China, and a tragedy for international organizations that depend on global cooperation to manage or solve issues that impact us all. [Source]