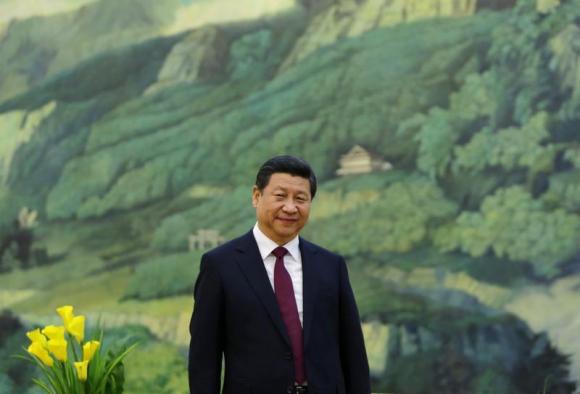

In the face of growing issues such as high government debt and the now-stalled trade war, Xi Jinping has convened hundreds of officials to signal alarm over domestic and international issues facing China. The New York Times’ Chris Buckley reports how such concerns have been echoed at political meetings nationwide, and how officials will be held accountable should anything go awry:

“Globally, sources of turmoil and points of risk are multiplying,” he told the gathering in January at the Central Party School. At home, he added, “the party is at risk from indolence, incompetence and of becoming divorced from the public.”

[…] “Beijing is confronting significant pressure from the international community over its political and business practices that only adds to its difficulties in dealing with its domestic issues,” said Elizabeth C. Economy, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York who wrote “The Third Revolution,” a study of Mr. Xi.

There are no political challengers on the horizon who could pose an immediate threat to the Communist Party or Mr. Xi. But his remarks made clear that especially in 2019 — a year of politically sensitive anniversaries — the party would aggressively extinguish sparks that could ignite protests and turbulence.

[…] Mr. Xi identified dangers that extended far beyond the economy, especially political risks like the party’s ability to keep young Chinese from slipping from its ideological orbit.

[…] Yet Mr. Xi’s demands for unyielding stability could backfire, experts say, as warnings of danger around every turn could smother the initiative and flexibility that Chinese officials need to defuse long-term economic and social dangers. [Source]

Reflective of this trend is an increasing number of Chinese entrepreneurs leaving China due to pessimism about Beijing’s management of the economy. At the New York Times, Li Yuan details their viewpoints:

Few are predicting a crash, but worries over China’s long-term prospects are growing. Pessimism is so high, in fact, that some businesspeople are comparing China’s potential future to another country where the government seized control of the economy and didn’t ease up: Venezuela.

Only one-third of China’s rich people say they are very confident in the country’s economic prospects, according to a recent survey of 465 wealthy individuals by Hurun, a Shanghai-based research firm. Two years ago, nearly two-thirds said they were very confident. Those who have no confidence at all rose to 14 percent, more than double the level of 2018. Nearly half said they were considering migrating to a foreign country or had already started the process.

[…] “The most important cause of their pessimism is bad policy and bad leadership,” said Minxin Pei, a professor at Claremont McKenna College in California who is in frequent contact with business figures. “It’s clear to the private businesspeople that the moment the government doesn’t need them, it’ll slaughter them like pigs. This is not a government that respects the law. It can change on a dime.”

Many members of the business elite are unhappy that the leadership’s economic policies favor state-owned enterprises even though the private sector drives growth. They are angry that the party is trying to put a Mao-era ideological straitjacket on an economy driven by private enterprises and young consumers. They are upset that the party eliminated term limits last year, raising the prospect that Mr. Xi could become president for life.

Many businesspeople feel increasingly insecure, especially as some entrepreneurs are “disappeared” by the government to assist in the anticorruption campaigns. [Source]

China has been facing backlash for its aggressive foreign policy practices on the international stage. U.S. concerns over Chinese technology companies such as Huawei’s ties to Beijing have spread to other countries, prompting concerns that it could heavily impair global 5G deployment. China detained 13 Canadians in the wake of the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, and recently retaliated against New Zealand for resisting its 5G push. China is also increasingly meeting strong pushback against its highly touted Belt and Road Initiative, and ongoing global condemnation for its re-education camps in Xinjiang—most recently by Turkey. For CNN, Ben Westcott cites observers’ concerns:

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute, said the backlash was the result of an unexpectedly aggressive foreign policy led by Xi. But he warned Beijing’s stance was unlikely to change.

[…] “Through fear and coercion Beijing is working to expand its ideology in order to bend, break and replace the existing rules-based international order,” Adm. Philip Davidson, the commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, said in Washington Tuesday.

[…] “There’s a panic about the China threat,” [Susan Shirk, chair of the 21st Century China Center at UC San Diego] said. “There’s a kind of rushing to erect walls, in a way that I see as an overreaction.”

[…] Tsang, the China expert, said if Beijing returned to the less aggressive foreign policy of Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, it could help defuse current international tensions. [Source]

For an in-depth take on why 2018 proved to be a difficult year for Xi Jinping, read this op-ed by Karim Raslan via South China Morning Post.