Proposed amendments to Hong Kong extradition laws sparked protests by as many as a million people on Sunday. On Wednesday, a smaller contingent, still in the tens of thousands, successfully derailed a planned legislative debate on the amendments in the face of an aggressive police response. While the new rules are not ostensibly aimed at mainland China, their opponents fear that by enabling extraditions to the mainland for the first time, they would demolish the “firewall” established between the two regions’ separate legal systems as part of the terms for the 1997 handover from British rule.

At the Hong Kong literary festival in November, a friend accompanied me at all times, for fear I'd be secretly kidnapped and smuggled to China. If the extradition law passes, any critic of Xi's regime could be legally, openly abducted. It would be the end of freedom in Hong Kong.

— 马建 Ma Jian (@majian53) June 10, 2019

NYU law scholar Jerome Cohen expressed similar concerns in a blog post on Wednesday:

It’s not only “Hong Kong people” whose fate is at stake here. Anyone passing through Hong Kong airport could be detained and sent to China (compare the Huawei Vancouver extradition case). Even people who have been extradited by a third jurisdiction to Hong Kong could be subject to re-extradition to China unless some provision is made in the extradition treaty between Hong Kong and the third jurisdiction to prevent that! This bill would undoubtedly lead those democratic countries that have extradition treaties with Hong Kong to either renegotiate them successfully or terminate them.

No criminal justice systems could be more different in practice than those of China and democratic jurisdictions including Hong Kong. Despite Xi Jinping’s occasionally expressed theoretical aspirations to promote a Chinese court system that will achieve justice in every case, reality is very different in the many cases that, for one reason or other, are regarded as “sensitive” in China.

[…] Some alleged offenders are never brought to trial in China. Think former Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, detained without any legal process for the last 16 years of his life!! Many are detained on spurious charges. Think Ai Weiwei, a famous dissident artist who was ostensibly detained on tax charges! How easy it would be for Beijing to conjure up charges that meet the tests of the forthcoming Hong Kong extradition amendments. [Source]

In a letter to The New York Times on Monday, Hong Kong’s commissioner to the United States Eddie Mak stated the government’s case regarding safeguards against such abuses:

Contrary to “The Death of Hong Kong as We Know It?,” by Ray Wong Toi-yeung (Op-Ed, nytimes.com, June 4), the Hong Kong government’s proposed amendments to extradition laws seek to enable us to effectively combat serious crimes by sealing the legal vacuum in our existing mechanism for surrendering fugitive offenders. They do not pinpoint any particular jurisdiction, nor do they target common citizens or affect the legal rights and freedoms of individuals.

Our independent judiciary will scrutinize each surrender request. No surrender action may be taken that is in conflict with a court decision against the surrender.

Given the range of procedural, judicial and human rights safeguards, the declaration that the proposed amendments would undermine “one country, two systems” and economic competitiveness is unfounded.

Our government has also proposed additional safeguards, like presumption of innocence, open trial and legal representation to ensure the rights of surrendered people. Hong Kong’s rule of law, judicial independence and human rights protection are held in high regard. Our commitment to safeguard these attributes remains rock solid. [Source]

In an analysis of the proposed amendments at Lawfare, however, Georgetown University’s Thomas Kellogg acknowledged the safeguards but questioned their adequacy, noting that similar reservations had deterred nearly all developed countries from signing extradition treaties with the mainland.

[… T]he Hong Kong government’s draft amendments bill contains several troubling provisions. Most prominently, the draft bill excludes the Legislative Council, Hong Kong’s legislature, from any role in overseeing the extradition process to countries without a treaty arrangement, even though the council has the power to block extraditions under existing law. Instead, the draft amendments bill assigns Hong Kong’s chief executive the leading role in the handling of extradition requests from nontreaty states.

The draft bill’s human rights safeguards are also quite weak. The bill does not explicitly empower Hong Kong’s courts to deny extradition if the individual’s right to a fair trial is at risk, for example. […]

[…] The Hong Kong government has also failed to adapt the law to Hong Kong’s particular circumstances. Given Beijing’s influence, both formal and informal, over all three branches of the Hong Kong government, the government needs to construct procedural safeguards that will blunt Beijing’s potential sway. For example, Hong Kong’s leader, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, was selected by a small circle of pro-Beijing electors; she was not directly elected by the people of Hong Kong. This means that she may be loath to cross Beijing, for fear of undermining her potential for re-selection. It also means, sadly, that there is no democratic check on her use—or potential abuse—of her authority under the proposed extradition amendments.

Hong Kong’s world-class judiciary is meant to be independent. Yet, in recent years, Hong Kong’s courts have found themselves facing increasing political pressure. Under Hong Kong’s Basic Law, Beijing retains the authority to interfere in highly charged human rights cases and has exercised that power as recently as 2016. More generally, as the political climate in Hong Kong has continued to decline, Hong Kong’s judges have expressed growing fears that they too will be squeezed by Beijing. One judge told an international journalist that “there is a marked climate of unease among my peers,” which “wasn’t there a few years ago.” [Source]

In an op-ed at CNN, Alvin Y.H. Cheung described the same shift:

In 2014, police cleared Umbrella Movement protesters from Mong Kok district not by exercising public order powers, but by enforcing a civil injunction obtained by private actors like minibus and taxi companies. The lawyer representing one bus company that obtained an injunction was part of a pro-Beijing political party in Hong Kong and attended a closed-door meeting with President Xi Jinping, along with a group of Hong Kong’s elite — raising questions that the injunctions amounted to the legal equivalent of “astroturfing,” or disguising the true sponsors of a political message to make it resemble a grassroots initiative. The fact that then-Secretary for Justice Rimsky Yuen had met with the “plaintiffs” in connection with what was supposedly a civil action brought by minibus and taxi operators strongly suggests that Yuen was using the suit as a fig leaf to conceal the suppression of peaceful protest. (Yuen has publicly disputed these allegations.)

More abuses of judicial process followed. In 2016, after pro-democracy and localist politicians — the latter advocate for the preservation of the city’s autonomy — made major gains in legislative elections despite pre-emptive disqualifications, the Hong Kong government took to the courts to demand the expulsion of localists Yau Wai-ching and Baggio Leung. Before the Hong Kong court could issue a ruling, an “interpretation” of the Basic Law — the territory’s constitutional document — by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee in Beijing effectively dictated the outcome of the case, by declaring that oaths of office must be made “sincerely and solemnly.” The “interpretation” became the basis for four further expulsions in 2017.

Further, the Department of Justice has abused its prosecutorial discretion to serve partisan political purposes by prosecuting pro-democracy activists and by demanding harsher sentences for them, while turning a blind eye to abuses by police officers during the Umbrella Movement. Although Lam has denied that her government engages in political persecution through judicial means, this pattern of prosecutions has prompted international concern. […] [Source]

On Twitter, journalism professor Yuen Chan described how these developments have contributed to a souring of the relationship between police and at least some parts of the public since 2014:

I grew up in South London in the Thatcher years. There was a lot of hostility towards the police. When I moved to #HongKong in the early 90s, I was struck by the genial relations between people and the police. They were generally liked and respected 1/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

#HongKong people were proud that their police force was not like the Public Security Bureau of China. There were always bad eggs but generally, the force was considered clean and professional. People trusted them 2/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

I covered and attended many protests over the years. In the past they were almost always peaceful and there was little aggro from the police. This began to change in the CYLeung years as Beijing tightened the screws and society became more polarised 3/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

And really took a turn for the worse just before and during the #UmbrellaMovement. I recently watched @LianainFilms Umbrella Diaries and it reminded me how people really tried to engage and reason with the police at the beginning “you’re HK citizens too…” 4/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

But things quickly deteriorated after the teargas was fired on 9.28, inappropriate use of force and incidents such as Ken Tsang’s beating in the “dark corner” and Frankly Chu’s baton attack on a Mong Kok shopper. Police began to adopt a siege mentality 5/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

But even with these incidents of brutality, some people still felt that overall, the police were caught between a rock and a hard place, bearing the brunt for popular anger over what were political decisions. But there were worrying signs of a hardening culture 6/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

Manifested in a mass rally attended by 33,000 former and serving officers in support for the cops who’d been convicted for assaulting Ken Tsang. They swore in unison, criticised the judge in the case and compared themselves to persecuted Jews in WWII 7/ https://t.co/c1PF37rlVf

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

Now #HongKongers and people around the world have been stunned at the level of violence the police have used against #extraditionbill protesters. Pepper spray, tear gas, batons, beanbag rounds, rubber bullets, smoke bombs inside the #LegCo bldg, harassment of journalists 8/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

The feeling in #HongKong is that the police have “gone crazy”, are “out of control”. At this point I’d like to point out that the man who led the police during #OccupyHK, Andy Tsang Wai-hung to head a UN agency to fight drug-crime. 9/

— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019

In the legislature, too, “the field has tilted toward Beijing” since the failure of national security legislation in 2003. From Keith Bradsher at The New York Times:

Beijing’s supporters now hold a larger majority in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council — 43 of 70 seats — than they did in 2003. Their camp consists mostly of professional politicians, rather than the patrician tycoons who once dominated the legislature. The tycoons had showed more independence, even if they generally sided with the government against the pro-democracy opposition.

In 2003, the attempt to push through the national security legislation collapsed when one of those tycoons, James Tien, grew alarmed by mass demonstrations. His pro-business political party withdrew its support for the bill, depriving the legislation of a majority.

But that is much less likely to happen with the class of lawmakers in office now. Some are far less affluent and more dependent on their $151,600 government salaries and generous expense accounts.

[…] In Hong Kong’s hybrid political system — a result of British colonial tradition as much as Communist control — only half the seats in the legislature are filled by popular elections. Most of the other half of the seats are filled by industry and business groups, and China’s booming economy means Beijing enjoys greater leverage over the Hong Kong economy now than it did even a decade ago, especially in finance. [Source]

The question remains, however, of why the proposed amendments have galvanized such a broad cross-section of Hong Kong’s population. An editorial supporting the protests in The Guardian emphasized their scale by noting that the reported turnout on Sunday would be proportionally equivalent to five to ten million protesters in the U.K.; similar extrapolation would give a figure of roughly 25 to 50 million in the United States, or 100 to 200 million in mainland China.

In 2014, the was a small but powerful constituency in HK opposed to universal suffrage, namely rich people. This allowed for high level of elite cohesion, which really mattered in withstanding such widespread and prolonged social insurgency.

— Eli Friedman (@EliDFriedman) June 12, 2019

Who in HK aside from Lam & co. actually wants the extradition law? Of course the localists, civil society orgs, labor, students, etc. are in the streets, but now big business is legit freaked out too. Does HKSAR bureaucracy or police support extradition law? (real question)

— Eli Friedman (@EliDFriedman) June 12, 2019

If demand for universal suffrage required at least a modicum of idealism, this time it’s about self- preservation… effects will of course be felt unevenly, but will threaten large swathes of HK society, rich and poor, HK and Mainland residents, and foreigners too.

— Eli Friedman (@EliDFriedman) June 12, 2019

Maybe the support of one man in Beijing is the only thing that matters to Lam. But seems to me the effort is totally without a constituency, hopefully that produces a sufficiently acute political crisis such that they’ll rethink things.

— Eli Friedman (@EliDFriedman) June 12, 2019

In an op-ed at The Guardian, Hong Kong-based lawyer and author of “City of Protest” Anthony Dapiran described the amendments as an affront to, and the protests an expression of, a new but deeply felt collective identity:

Unlike in 2014, the protesters have two advantages which may increase their chances of success. Then, they were trying to push the government to adopt a “genuinely democratic” means of electing the territory’s chief executive – although specifically which model of genuine democracy the protesters could not quite seem to agree upon. This time, their request is simple: they want the government to drop a proposed new extradition law. And it is truism in politics that it is easier to oppose than propose.

The protesters’ second advantage is that public opinion seems to be much more solidly unified behind them this time. Over one million people took to the streets of Hong Kong on Sunday to protest the proposed new law. Why has this issue galvanised public opinion and provoked a response like no other in recent years?

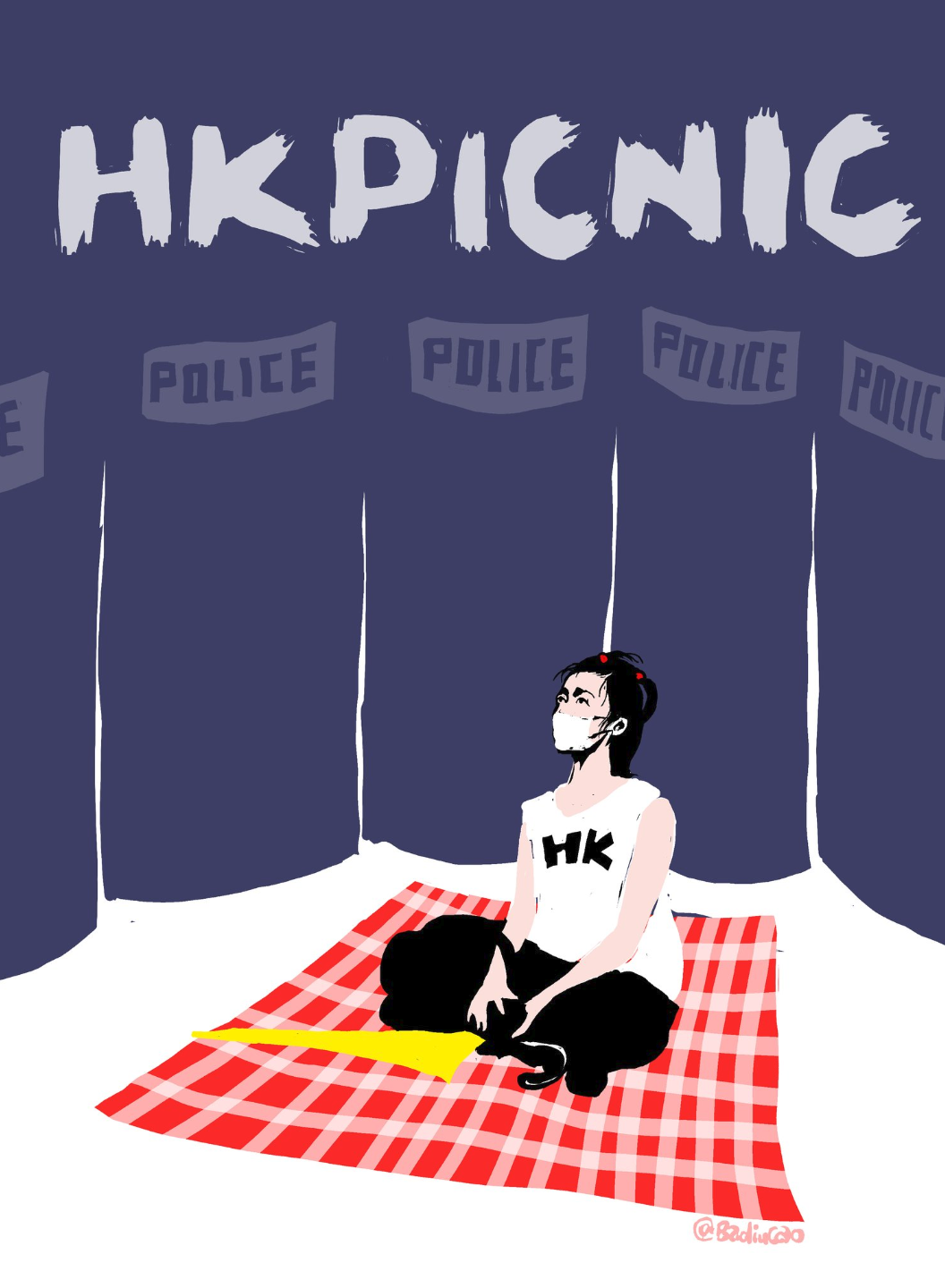

[…] In the past, Hong Kong had distinguished itself on the basis of wealth: Hong Kong was rich, while the rest of China was struggling to bring its population out of poverty. However, over the twenty years since the handover in 1997, as Hong Kong’s economy has drifted and China’s boomed, that distinction has failed to hold. Pride rooted in materialism has been replaced by a deeper pride among Hong Kongers, based around the notion of “Hong Kong Core Values”, those rights and freedoms enjoyed by Hong Kong that distinguish it from the rest of China. Hong Kong Core Values include: a lively and unfettered media, the right to participate in the electoral and governing process, freedom to criticise the government, rule of law and due process, an independent judiciary, and, of course, the right to protest. “Hong Kong core values” has become the answer to the question: “What does it mean to be a Hong Konger?”

The current proposed extradition law, by blurring the line between the Hong Kong and mainland justice systems, is seen as another attack on Hong Kong core values. The million people on Hong Kong’s streets on Sunday and those gathering again today are protesting not just against a theoretical risk of extradition to the opaque mainland criminal justice system; they are protesting a threat to their very identity as Hong Kongers. And by taking to the streets, they were expressing their dissatisfaction by exercising of one of those key rights and freedoms: I am a Hong Konger, therefore I protest. [Source]

The Economist’s Chaguan column suggested another angle:

A POWERFUL INSIGHT of modern psychology is that humans are hard-wired to fear loss, and will take greater risks to avoid it than to realise a gain. Such insights help to explain protests that have paralysed central Hong Kong in recent days. […]

[…] When Chaguan last year met Benny Tai, a rumpled law professor from Hong Kong University and an Occupy Central leader, he sadly wondered when his city might witness large demonstrations again. “People are concerned that it is not safe to protest, especially in the business sector,” he sighed. He talked of “holding the line” while waiting for democracy in mainland China. It would be interesting to hear Mr Tai’s views now, but he is currently in prison.

An American newspaper this week asked if China had created a million new dissidents in Hong Kong. That is to mistake the mood. The protesters are not marching to gain new freedoms, but to avoid losing those that they still have. Anson Chan, who served as chief secretary of the Hong Kong government under the British and for the first four years of Chinese rule, spent four and half hours among the marchers on Sunday. Many probably “held out very slim hope that the government will change these proposals”, she says. “But they wanted to stand up and be counted.”

[…] It is a clarifying rebuke for China’s rulers. Exposure to their version of the rule of law feels like an unbearable loss to many in Hong Kong, outweighing the rewards of integration with a faster-growing China. Assuming that the extradition law is rammed through anyway, it will be a win for fear and resignation, not love. [Source]

At Inkstone News, Arman Dzidzovic gathered some explanations from several of Wednesday’s protesters, including 25-year-old Jackey Wong:

This extradition law is really unfair. We don’t believe in human rights protections and the rule of law in mainland China. If the bill passes, we would not be able to say what we want to say. We would be like meat on a chopping board, at the mercy of the government.

That’s why we have come out, hoping the government could hear our voices. This is definitely not our last chance, but we have to seize every opportunity we have. We never know when the next chance will come. [Source]

Journalist Jessie Pang offered her own answer in a blog post at Medium:

Too many thoughts in my mind right now that I must write it out. Even though as a journalist you are supposed to be neutral, I am a Hong Konger. I need to say something for us and Hong Kong.

No one wants to be fired by tear gas, pepper spray, bean bags, rubber bullets or batons. Yet, the entire generation has come out fearlessly even it means it could risk their life. Why?

“Why?” A simple but perhaps the most complicated question I kept asking myself and many protesters today. We all know the government is not going to listen to her people; we all know the legislative council is going to pass the bill; we all know no matter how hard we try, there’s no miracle. And yet, despite all the disappointments and heavy prices that we have paid in the past five years. We are still hoping for a miracle to happen.

“Every time is our last time to defend Hong Kong. If we don’t come out every time, there won’t be next time. Somebody has to come out. That’s why I come,[” …] said a 26 years old protester. [Source]

A friend just WhatsApped, recalling a young person on the frontline: "We can't lose again, because if we do, we lose everything!" And then he charged forwards.

My friend is in tears recounting those words#HongKong #ExtraditionBill— Yuen Chan (@xinwenxiaojie) June 12, 2019