Revelations of serious quality defects in many Chinese brands of sanitary pads have sparked outrage, led to a run on imported menstrual products, and fueled an online campaign that has prompted regulators to vow reforms and forced some major pad manufacturers to apologize to consumers. The defects range from product mislabeling (such as overstating the length of pads, a common offense) to health-threatening contamination due to insect infestations, improper pH levels, or excessive use of plastics, formaldehyde, fluorescents, PFAS, phthalates, and other chemicals in the manufacturing process. (The problem is, of course, a global one, and industry standards vary widely from country to country.)

For many Chinese women, the scandal is but the latest insult in a socio-economic and political system that frequently prioritizes the interests of men over women, and too often makes light of women’s legitimate concerns about physical safety, product safety, and gender inequality and discrimination. As one Weibo user commented recently, “When women have problems, [the authorities] pretend to be blind and dumb, but when they want something from us, they won’t shut up about it.” Some social media users criticized the All-China Women’s Federation for remaining silent on the issue: the Federation is increasingly being seen as inexcusably passive on issues that matter most to women and families, and far too compliant when it comes to doing the bidding of the Party-state.

Several recent articles, including two archived by CDT editors, have addressed the recent menstrual-products scandal. An article titled “Could Our Standards Possibly Fall Any Lower?” from WeChat account 竹不倒 (Zhú bù dào, "Bamboo never falls") bemoans the glaring lack of consumer product oversight that makes China’s annual March 15 Consumer Rights Day seem “like a drop in the ocean.” The author mentions some other product-quality scandals that have hit the news in recent months, including fake hot-pot ingredients, ersatz pig ears adulterated with glue, and down jackets that are either underfilled or stuffed with materials that break down into particles that are harmful if inhaled. A portion of the article describes the recent rush to obtain sanitary pads imported from Japan and explains the very real health hazards of substandard period products:

The pH value of sanitary pads falls on a scale of between 0 and 14, ranging from acidic to alkaline. Values below 7 are acidic, and those over 7 are alkaline. The pH of a woman’s vagina is usually around 4.5, which is on the acidic side. Coming into contact with an overly alkaline sanitary pad increases the likelihood of problems such as allergic reactions, rashes, and vaginal or urinary tract infections.

After this latest scandal came to light, many women couldn’t hold back, and accused domestic manufacturers of being "morally bankrupt" and essentially expecting their customers to "put a swatch of curtain fabric next to their private parts." I don’t feel there’s anything wrong with that sort of criticism—it’s just telling the truth!

Then people started flocking to stock up on Japanese sanitary pads—some even asked Chinese friends living in Japan to buy some for them—and it turned into a frenzy.

Japan, by the way, has its own standards, which require the pH value to be close to neutral or slightly acidic, and not to exceed 6.5.

That’s quite a high standard, actually. The U.S. standard is between 4.5 and 7. Europe is even more particular, with extremely strict standards for such products, which must have a pH in the range of between 4.5 and 5.5. The penalties for exceeding that range are severe. But since we can’t get European sanitary pads, we have to settle for the next best thing and stock up on some Japanese ones.

It’s ironic that now people are no longer cursing the Japanese or boycotting Japanese products, but only yesterday they were still grousing about the new visa-free policy for travelers from Japan. [Source]

An article by Chen Dazhuang for Caijing Tianxia (Economic Weekly), “Sanitary Pads: Stop Letting Women Down,” reveals the already extremely low quality standards to which women’s period products are held—in contrast to other products such as diapers and baby clothes:

The textiles we buy daily are divided into three types, based on who will be using them and how: infant textile products (such as diapers, underwear, and bibs); textile products that come into direct contact with the skin (such as underwear, shirts, pants, and towels); and textile products that do not come into direct contact with the skin (such as outerwear, curtains, bedspreads, and wall coverings).

The technical standards for textile products differ according to how they will be used. Infant textile products must meet Type-A standards, products that come into direct contact with the skin must meet minimum Type-B standards, and products that do not come into direct contact with the skin must meet minimum Type-C standards.

Other than formaldehyde content, the most straightforward indicator distinguishing product types A, B, and C is the pH value. The pH value for Type-A products is limited to a range of 4.0-7.5, whereas for Type B it is 4.0-8.5, and for Type C, 4.0-9.0.

Here is the salient point: sanitary pads come into direct contact with the skin and are used in the most sensitive areas of the body. Netizens naturally assume that these are classified as Type A, the same as infant textile products, but the standard pH range for sanitary pads is 4.0-9.0, consistent with the range for Type-C textiles.

Extrapolating from this, some netizens have claimed that using women’s sanitary pads is comparable to "putting a swatch of curtain fabric next to your private parts." [Chinese]

In a longer article from WeChat account 青年志Youthology (Qīngnián zhì Youthology), author Liu Tian asks: “Is It Really So Difficult to Make a Safe, Easy-to-use Sanitary Pad?” Liu’s article, which includes detailed footnotes and references, highlights nine aspects of the ongoing debate about menstrual products in China and worldwide. "But we also hope," the author writes in the preface, "that people will not confine their attention to the issue of sanitary pads alone. For this, like many other things in our society, is something that is ignored, stigmatized, and belittled—simply because we are women."

Pad Length

[…] In order to reduce costs and maximize profits, manufacturers chose to make sanitary pads shorter rather than longer, within the ±4% fluctuation range allowed by the national standard. At the same time, although China reduced the tax on menstrual products, the price of sanitary pads did not drop.

The average gross profit margin in the sanitary products industry can be as high as 45%. […]

National Standards

[…] The pH value of most of these consumer products is around 6, which is in line with the national standard. However, the normal pH of a woman’s vagina is between 3.8 and 4.5, so the most fundamental problem is with the national standard. Why is the acceptable pH range so broad? How was this range determined? Is it mere coincidence that the range coincides with that of Type C products? Although the national standards for female hygiene products were revised twice—in 2008 and 2018, respectively—neither revision involved an update to the pH-value range.

Health

[…] Data shows that 48% of sanitary napkins and panty liners, 22% of tampons, and 65% of menstrual underwear were found to contain PFAS (a group of over 12,000 synthetic chemicals). PFAS are used to make materials more absorptive and stain resistant, but they are harmful to our health and may cause negative physical effects such as decreased fertility, high blood pressure in pregnant women, increased risk of certain cancers, hormonal disorders, high cholesterol, and decreased immune system response.

Among the menstrual products that tested positive, more than half claimed that their products were "natural and organic, containing no harmful chemicals." Sanitary napkins are sterile products, but manufacturers are not required to disclose any ingredients on their packaging. In other words, consumers have absolutely no way of knowing what harmful substances sanitary pads might contain.

Marketing

Why is the menstrual blood in sanitary-product ads always blue? Why is menstruation euphemized as “those days”? What’s the deal with the advertising slogan, “That can be pain-free, and every month a breeze”? What “that” are they talking about? Globally, 71% of women under 25 have suffered from dysmenorrhea (period pain), so why are the women in those sanitary product ads always so polished and perky? Who actually watches these ads, and who determines their standards and aesthetics? […]

Substitutes

Recently, searches for "medical-grade sanitary pads" on online shopping platforms have increased by nearly 40-fold, and the price of medical-grade pads have soared. Some women have begun promoting the use of menstrual cups and menstrual discs.

In terms of environmental protection and cost-effectiveness, menstrual cups and sanitary discs are indeed better choices, but this does not mean that the problem of sanitary napkins being difficult to use should be overlooked. Moreover, the state of China’s product-manufacturing technology and public-toilet hygiene may make these [alternative] products unsuitable for long-term use. Many women may also be deterred by the idea of, and the cost of, more physically invasive period products. They may not be suitable for women living in culturally conservative or economically impoverished regions [….]

From the very first day she starts her period, menstruation creates an additional financial burden in a girl’s life.

In 2018, India scrapped its 12% tax on women’s sanitary products. Twenty-seven countries including the U.K., Ireland, Canada, and Australia charge no tax on sanitary products. But in China—where condoms are tax-free; and grains, cooking oil, and publications are taxed at a rate of 9%—sanitary products are subject to a 13% tax rate.

The average menstrual period for Chinese women lasts 5.8 days. If she were to change sanitary pads every four hours, the average woman would use 30 pads during each menstrual period. At that rate, even buying a relatively cheap brand of sanitary pads would amount to 1,040 yuan [$143 U.S. dollars] per year. […] At present, there are still 600 million people in China whose monthly income does not exceed 1,000 yuan [$137]. […]

Disability

For those with mental or physical disabilities, changing and using sanitary pads can be much more challenging.

[…] We need to recognize that women’s menstrual needs can vary, and therefore, all period products should be equally accessible and “barrier-free.”

The “Second Sex”

Women, who make up half of the world’s population, get their periods every month, yet they still cannot easily get period products at high-speed rail stations or shopping malls. In the U.S., it wasn’t until 1992 that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conducted any research into women’s sanitary products—because before that, women had never held senior positions at the NIH.

Menstruation is deliberately ignored, just as women are frequently made "invisible." In the book “Invisible Women,” the author lists numerous examples of gender data gaps to illustrate how women are “othered” and consigned to being the “second sex.” Yet these gaps affect women’s lives each and every day. […]

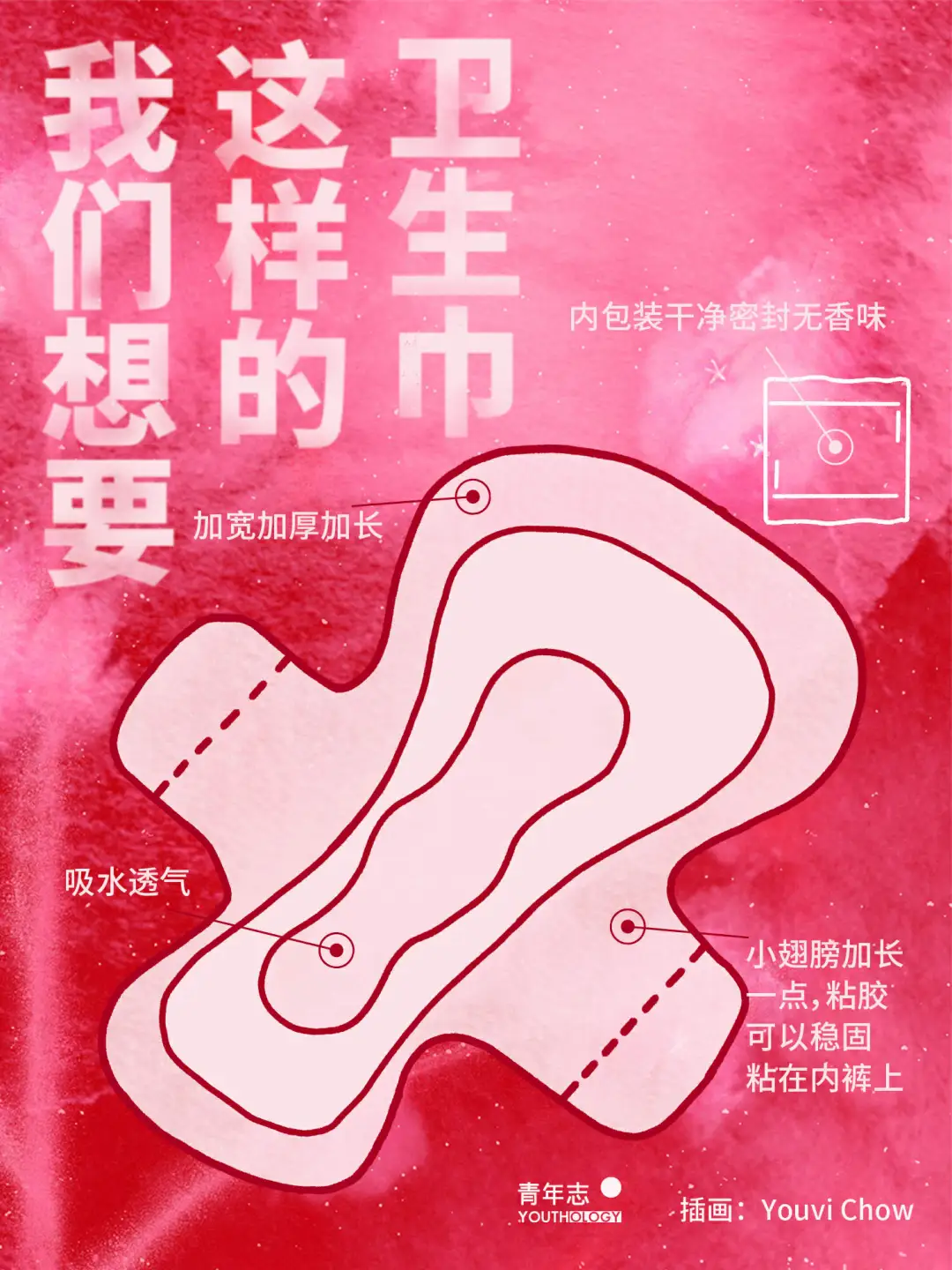

We Want Pads That Look Like This

Large text reads:

We want sanitary pads that look like this.

Small text, clockwise from top right:

Individual packaging that is clean, sealed, and unscented.

Slightly longer wings with tape that firmly adheres to underwear.

Absorbent and breathable material.

Wider, thicker, longer pads. (source: Youvi Chow/Youthology)[…] In addition, new national standards for sanitary pads are currently being drafted. We invite everyone who cares about women’s health and product safety to join in and take action. Please follow this link for more information. [Source]

Food- and consumer-product safety has long been a concern in China, with scandals erupting periodically. Some, such as the recent controversy about edible oils being transported in fuel tanker trucks that were not washed between transports, eventually result in regulatory reforms and stronger oversight. But almost without exception, news and discussion about product safety scandals are heavily censored online. In addition, some journalists investigating product safety have been threatened or targeted by authorities, and netizens who share news about quality defects have been accused of spreading rumors or “fake news” online.