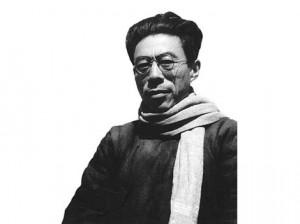

Wen Yiduo, poet, professor, and staunch critic of the Kuomintang (KMT), was unafraid to speak his mind. Born to a wealthy family in 1899, he came of age during the fall of the Qing dynasty and the tumultuous years of the early republic. While studying painting in the United States in the early 1920s, Wen turned his sights to poetry. He joined the Crescent Moon Society in 1928, where he emphasized the importance of “formal properties” in poetry. “Stagnant Water” is the title of his best-known poem and the collection of poems by the same name.

Wen Yiduo, poet, professor, and staunch critic of the Kuomintang (KMT), was unafraid to speak his mind. Born to a wealthy family in 1899, he came of age during the fall of the Qing dynasty and the tumultuous years of the early republic. While studying painting in the United States in the early 1920s, Wen turned his sights to poetry. He joined the Crescent Moon Society in 1928, where he emphasized the importance of “formal properties” in poetry. “Stagnant Water” is the title of his best-known poem and the collection of poems by the same name.

Wen became a professor and literary critic once he returned China. Fiercely opposed to the Nationalists, he walked out of his office at the Democratic Weekly one June day in 1946 to be greeted by a shower of bullets. Mao blamed the Nationalists for Wen’s death, elevating the poet to heroic status.

Robert Dorsett has translated Wen’s work in the new volume Stagnant Water & Other Poems. Dorsett, who was a physician before he devoted himself to writing full-time, has published his own poetry in The Kenyon Review, Poetry, and other literary journals. He has also translated Gao Ertai’s book In Search of My Homeland: A Memoir of a Chinese Labor Camp.

Dorsett’s new translation of Wen Yiduo’s poetry is accompanied by the calligraphy of Huang Xiang, a poet and artist who left China after multiple imprisonments for his advocacy of human rights. Huang was the first writer in residence at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh from 2004-2006.

Anne Henochowicz, CDT’s translations editor, corresponded via email with Dorsett about the process of translating Wen’s poetry. Read the poems “Stagnant Water” and “Tiananmen” at Beijing Cream, reproduced with permission from the publisher.

China Digital Times: In the forward to Stagnant Water, Christopher Merrill notes that other translators have translated the phrase sishui 死水 as “dead water.” What made you decide to do your own translation of “Stagnant Water”? Where does your version depart from previous work?

Robert Dorsett: Sishui, Wen Yiduo’s signature poem, has probably been translated more than any of the others. Although the word sishui, has been rendered as “dead water” in most previous translations, it is a common Chinese idiom that means simply “stagnant water.” In my opinion, to insert a poetic sounding metaphor for a common idiom, although I’ve done it elsewhere, skews this poem.

I feel Wen Yiduo means that only if we accept reality as it is are we able to build something better in the future; he parallels this idea by using ordinary words to say very extraordinary things. In general, I wanted to make translations that not only captured the depth, subtlety and irony of the originals, but also sounded natural, as if written originally in English. I tried to avoid making the foreign sound strange.

CDT: Wen loved to work in poetic forms, such as the sonnet in “You Pledge by the Sun” and the roundel in “Forget Her.” Your translations largely forgo rhyme and meter, but still transmit Wen’s voice. How did you reconcile Wen’s emphasis on form in your translation?

RD: Rhyme and meter present difficulties. There are more identical rhyme words in Chinese, so rhyme is easier to accomplish; however, these words usually differ by tone. This effect doesn’t exist in English. Also, applying an English metrical system often gives the translation a stilted feel and obscures the clarity of the voice. I would say it is possible to do, and a very valuable thing to do, but I feel it would take a poet with as much skill in English as that consummate master, Wen Yiduo, has in Chinese. Even if successful, I think such a translation would necessitate so many changes that it would more properly be termed “based on” rather than “translated from.”

CDT: Wen himself worked within the tension between the classical Chinese of his education and the vernacular advocated by his contemporaries. Are there poems where one type of language wins over the other, or where one makes a conciliatory bow to the other?

RD: I believe after the beginning of the May Fourth Movement, Wen Yiduo was committed almost entirely to the vernacular. After his return to China from the United States, he became a leading expert in classical Chinese literature but always sought to make that literature immediate and relevant. He resisted most of his contemporaries who urged the use of politically dominated free verse. His most conversational poems still have formal excellence: “The Rickshaw Puller” and “The Fault,” for example.

Wherever he found a conflict within himself, he didn’t resolve it, but used that conflict as a source of power. Only by the possession of the past and by its application to the present can a future be built: I believe this was his philosophy.

CDT: Where did the poems outside of the collection Stagnant Water come from? When were they first written, and where did they first appear? How did you choose them for this volume?

RD: Besides those in the Stagnant Water section, all poems, with the exception of “Miracle,” come from the earlier collection, Red Candle, published in 1923. The Stagnant Water collection was published in 1928. My sources were Wen Yiduo Quan Ji (聞一多全集), published by Far East Publishing Co., Hong Kong in 1968 (no ISBN) and a more handy, pocket sized edition, Hong Zhu, Sishui (紅燭·死水), published in Hong Kong by Joint Publishers in 1999. Wen’s poems often exist in several versions; I kept to, almost exclusively, these two sources. I chose poems for their literary excellence and for their variety.

CDT: Is the poem “Tiananmen” about the May Fourth protests, or another incident? How does it resonate with the student protests of 1989?

RD: Wen wrote the poem Tiananmen shortly after his return from the U.S. It may refer to an incident that occurred on March 18, 1926, when students protested the power of the warlords and the concessions given to foreign powers. I am not qualified to discuss the differences between that demonstration and the later 1989 demonstrations. However, the March 18 incident must have reminded Wen of the May Fourth protests.

CDT: Wen studied in Chicago, Colorado, and New York from 1922 to 1925, rubbing shoulders with American poets like Amy Lowell, Harriet Monroe, and Carl Sandburg. Did his time in the U.S. affect his political leanings in any way? As for his poetry, how does the American influence show through in his work?

RD: I believe the English Romantics influenced Wen most, especially John Keats. To my ear, “What Have I Dreamed” is similar in tone to “Isabella,” and “Forget Her” echoes Sir Thomas Wyatt’s “Forget Not Yet.” In addition to western forms, such as the sonnet and ballad, Wen also struggled to adapt English metrical rules to Chinese. I can’t help but to think Carl Sandburg encouraged Wen’s use of the vernacular.

I think Wen was offended by the exclusions he suffered in the U.S., and, because of this, he became more nationalistic. As I mentioned before, after his return to China, he became a famous classical scholar.

CDT: Wen was assassinated in 1946, allegedly by the Nationalists, and Mao lionized him. How has Wen’s place in Chinese literature and the building of the nation changed from his death to the present? Is his work still published, uncensored, in China today?

RD: I am not privy to the status of Wen Yiduo studies in China, but I can say there was an edition, Wen Yiduo: Selected Poetry and Prose, published as a Panda Book in Beijing in 1990, and also a commemorative edition published by the National Library of China Publishing House in 2007; a two volume edition of his letters was also published by the same house in 2010. Reading these, I cannot detect any systematic censorship of this poet.

CDT: You worked as a pediatrician before you devoted yourself to writing full-time. How, if at all, does your medical training inform your approach to poetry and translation?

RD: I often asked my residents and medical students to describe a patient exactly, so that, when I saw the patient, what I expected to see and what I did see coincided. I then asked them to combine what they saw with what they had learned in school and to put that into words. This process of observation, capturing that observation in words, and then being able to communicate it, is similar in poetry. It is a matter of discipline.

CDT: Were you involved in selecting the passages to be written in calligraphy for the book? If so, could you talk about that process?

RD: I suggested five lines to Huang Xiang which I felt epitomized Wen Yiduo’s themes. They are in rough paraphrase: “look at the blue ridges but not beyond for your home” (exile), “the Death God barks” (commitment, anti-war), “from my mind radical thoughts break out” (originality, passion), “an arrogant storm tramples the world” (protest, suffering), and “in the half-parted door, You” (inspiration, vision). Mr. Xiang was, of course, free to use his own inspiration. I feel he did beautiful work.

CDT: What is your favorite among the poems in this volume, and why?

RD: I have many favorites, but I’ll mention “Peddler Songs,” because it’s, at least in the Chinese, a little masterpiece. The poem starts in the morning, ends at night, recounting one day in the life of three generations of an upper class family. The only connections this family has with the lower classes are the peddler calls and the aromas of their wares, which Wen represents by nouns of separation (wall, screen, etc.) and verbs of transit (drifts, passes, etc.). The last call is by the poet himself to the reader across the barrier of the page: an example of Wen’s nuanced brilliance. All this is compressed easily, naturally, in four short stanzas.

A Wen Yiduo poem is like a jewel: its luster is a function, not of its surface, but of its depth. You can see why I think this poet is very special.