The announcement of a disciplinary investigation into Zhou Yongkang on Tuesday has unleashed a wave of news content prepared by Chinese media during the months in which his fate was known but unofficial. The permissible angle of coverage has been made clear by propaganda authorities, and lingering censorship online shows that some aspects of the case remain off-limits. But the former domestic security chief and Politburo Standing Committee member, the highest official to fall in China in decades, can now be named outright, instead of by indirect references like “Zhou Bin’s father,” “Master Kang” or “You Know Who.” Global Times’ Chang Meng reports on the immediate appearance of pre-prepared material such as infographics:

These sophisticated designs, especially those developed by big news portals such as Sina and Netease, were clearly well-prepared and waiting for the news. They mostly illustrate Zhou’s intricate power networks, his family members, and a timeline of the downfall of his key protégés, which led to his own investigation step by step.

Meanwhile, Zhou’s name, which was a censored word on China’s search engines and social networks, was unbanned almost immediately.

A large number of investigative reports digging into the power-growing and money-making history of Zhou’s network, represented by a series of five stories published by caixin.com, went viral online Wednesday. [Source]

A piece on Caixin’s English site also describes the “opening of the media floodgates.” Its main Chinese site, like many others, has a special focus page on Zhou’s case presenting new reports and an impressive animated illustration of Zhou’s network alongside earlier material.

Surveying the melee at Reuters, Megha Rajagopalan noted that veiled coverage of Zhou’s case had received an apparent green light some months ago:

A reporter from the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post raised the question of Zhou’s status with a government spokesman at a press conference at the start of China’s annual parliamentary session.

[…] “Actually, I’m just like you, I’ve gotten information from some media reports,” the spokesman responded with a nervous grin, saying that corrupt officials would be punished regardless of their status or position.

“I can only say that much,” he added. “You understand.”

The phrase “you understand” was taken by Chinese media as a signal that censors might tolerate deeper reporting of the Zhou case, analysts said. [Source]

Nevertheless, the effect of Tuesday’s announcement was like a starting pistol:

Astonishing number of Zhou Yongkang-related exclusives in Chinese press past couple days — lots of editors holding stories til this week

— Megha Rajagopalan (@meghara) July 31, 2014

Among the more colorful threads in the new coverage are rumors of wife-swapping and more than 400 mistresses including Gu Kailai, the wife of fallen Chongqing Party chief and Zhou protégé Bo Xilai who was convicted in 2012 for the murder of Briton Neil Heywood. (The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection recently warned that adultery with as few as three mistresses would be regarded as misconduct.) Other rumors accuse Zhou of involvement in the death of his first wife, after which he soon married a much younger CCTV presenter. The Telegraph’s Malcolm Moore reports suspicions about the origins of such lurid tales:

The sudden swathe of reporting about Zhou’s wives and family may be part of a campaign to smear him in the public eye or may be the natural exuberance of a media that has been restricted for years, said one senior Chinese investigative journalist.

[…] “The readers tend to enjoy the stories as they would enjoy a novel. They do not really take it seriously and you can never tell how much of it is true,” he added. “Some people in the government may be happy to see the information released, but it is hard to say whether the government is ordering the publication.”

[…] “This stuff is leaked out by the investigation team to smear him,” [one well-connected source in Sichuan province] said. “In Sichuan there’s a tradition of gossiping that party leaders kill their wives. The wife of one of Zhou’s predecessors, Yang Rudai, died in a car crash in 1993. People used to say he killed her.” [Source]

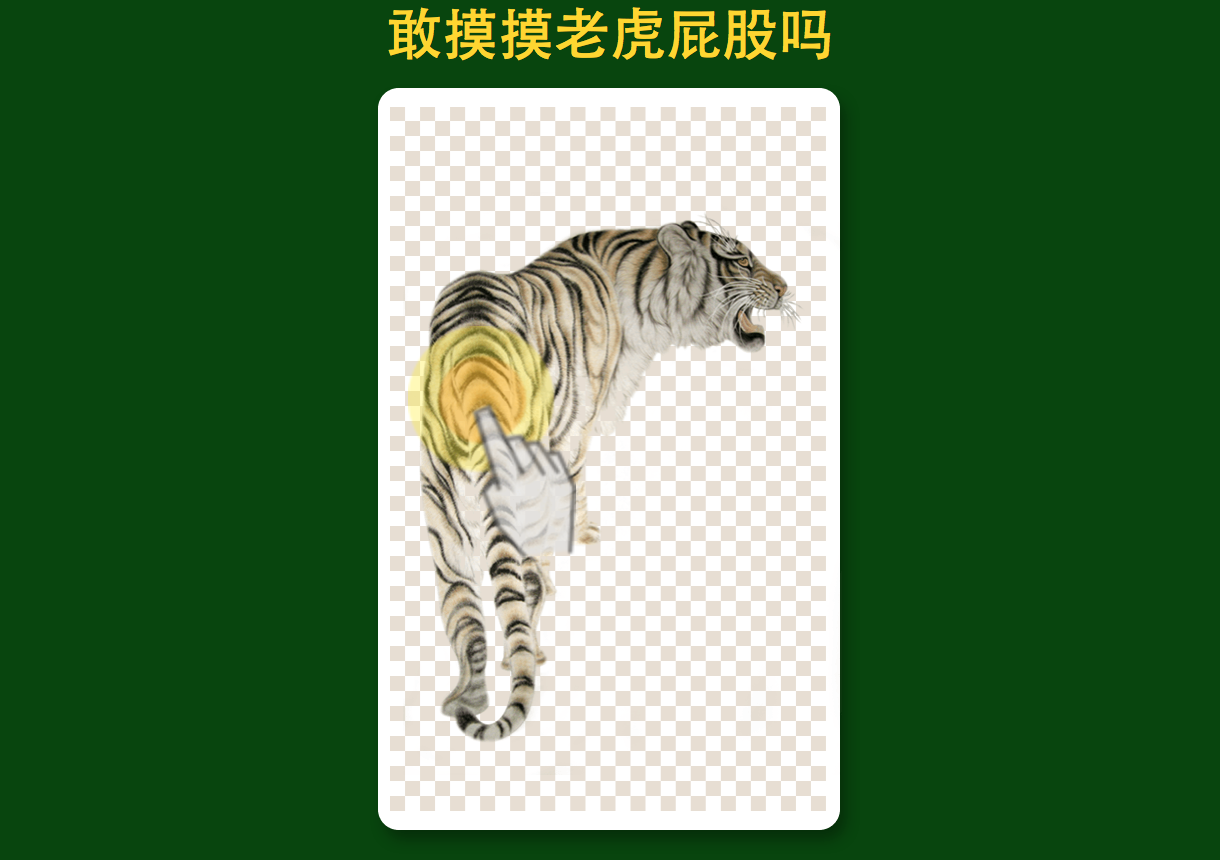

The newly open irreverence is vividly illustrated by a quiz game on Tencent’s QQ site and WeChat messaging service, entitled ‘Do You Dare Touch The Tiger’s Butt?’ David Tweed at Bloomberg explains:

The mere fact that WeChat’s almost 400 million users can access the game reflects how discussion of Zhou’s fate is no longer taboo, and may even be encouraged, as the Communist Party builds support for a case against him. The game highlights the shifting censorship landscape in China where leaders and sensitive topics may be off limits to ridicule for years – until they’re not.

[…] Tapping on the tiger prompts a choice of four virtual playing cards with the names of Zhou’s spheres of influence: the oil industry, where he once led state-owned China National Petroleum Corp.; Sichuan province, where he served as party secretary; internal security; and his family.

Selecting a card, gamers may test their knowledge of Zhou’s network of company executives, government officials, military personnel and family connections. The right answers wins the accolade, “You’re a tiger-beating hero.” [Source]

If the leash has been loosened, though, it is only to serve the Party’s purposes. The Economist (via CDT) reports that China’s media policy remains a long way from “letting a hundred flowers bloom.”