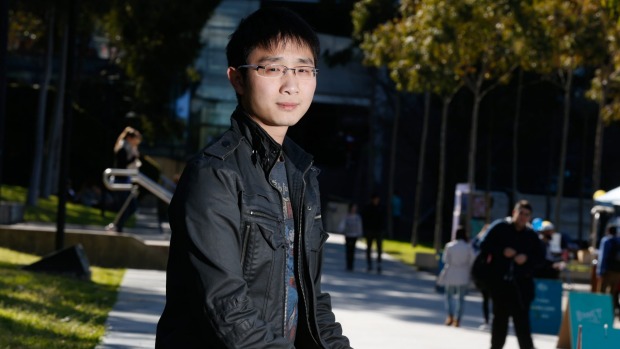

Xin Lijian was detained in August for providing financial support to liberal intellectuals. Now his son, Sydney University law student Xin Hongyu, has been advised to refrain from traveling to or communicating with contacts in China due to fears of collective punishment, a tactic that the Chinese government has increasingly resorted to in recent years. John Garnaut at The Sydney Morning Herald reports:

His father, an important financial patron of liberal intellectuals, disappeared in the middle of the night three weeks ago, amid China’s deepening political crackdown. And one distinguishing feature of this crackdown, apart from its severity and duration, is that security forces have been targeting children to put pressure on their parents to confess.

“If Hongyu returns to help his family in Guangzhou, he is likely become a hostage,” said Professor Feng Chongyi, of the University of Technology, Sydney, who is a friend of both father and son. “This is a return to the old imperial system known as ‘punish the nine categories of relatives and friends’.”

Officially, businessman Xin Lijian, 60, was arrested in the early hours of August 22 for accounting irregularities. […]

[…] But the real reason for his arrest, they say, is that he is provides crucial financial and other channels of support to a constellation of leading liberal writers, economists and other public intellectuals. They include Sydney blogger Yang Hengjun and former Guangzhou newspaper editor Chen Min, who writes under the pseudonym Xiao Shu. His downfall shows how President Xi Jinping’s two-year civil society crackdown is now undermining the political foundation of China’s economic reforms, said Xiao Shu. [Source]

In an open letter written to Chinese President Xi Jinping, meanwhile, Zhang Qing, the wife of detained Chinese human rights defender Guo Feixiong, details the plight that her family has suffered since her husband was put behind bars two years ago for “disturbing public order.” From Front Line Defenders at Medium:

I remember one time when my nine year-old daughter was followed too closely. She was frightened and quickly moved ahead of them, but the police still pursued her, moving even closer. When she got home she said: “If only I could do magic, I would make them vanish!”

The persecution of our family later escalated to the point they would no longer allow my two children to attend school: The police threatened Guo Feixiong: “We won’t let your son go to primary school. We won’t let your daughter continue on to middle school.” And they did exactly as they said. My children had to be out of school for a year. When my daughter matriculated, all of her classmates had middle schools to go to, but my daughter didn’t. I remember that every day I was worried about my daughter moving up into middle school — I wrote open letters, and went out constantly to look into schools.

Every time I came him, my daughter would open the door for me. Timidly, she would ask: “Have you found a school?” “No,” I would say, a lump in my throat.

They don’t just use prison, inflicting torture on adults — they make things impossible for children, thinking nothing of destroying a child’s future. This sort of cruelty visited on associated [innocents] must be a rare thing whether in ancient times or in the present day, don’t you think? For me, this has been the greatest pressure, and this is the main reason we moved to the United States [in 2009] with the help of friends. [Source]

Elsewhere, loved ones of missing lawyer Li Heping, who was detained during an unprecedented “Black Friday” government crackdown on human rights lawyers two months ago, are speaking out despite warnings from the government to refrain from giving interviews to foreign media. John Sudworth at BBC reports:

Wang Qiaoling has been warned by the police not to give interviews to the foreign media but has decided to ignore the threat that it will make her husband’s case worse.

“If I don’t step forward, who’s going to speak for him?” she asks me. “I am his wife.”

Ms Wang’s nightmare began exactly two months ago, on 10 July.

[…] Sixty-one days later and counting – long past China’s upper limit of 37 days before the police have to charge or release a suspect – there has been no official notification of his whereabouts, his health and wellbeing or any details at all regarding the crimes for which he is supposedly under suspicion.

[…] In total, according to the figures compiled by the Hong Kong-based China Human Rights Lawyers’ Concern Group, since early July more than 280 human rights lawyers and activists and some of their relatives and assistants have been either summoned for questioning, formally detained or simply disappeared. [Source]

Meanwhile, Human Right Watch is calling on the United Nations Human Rights Council to hold China accountable for the death of human rights activist Cao Shunli. Cao was taken into custody two years ago yesterday and who subsequently died in detention after being denied medical treatment for several months.

“Cao Shunli paid the highest price for trying to participate in China’s rights review at the Council,” said Sophie Richardson, China director. “At the two-year mark of the detention that led to her death, it is shocking that there has still been no accountability, or any sign of an investigation.”

[…] Chinese authorities provided little explanation for their conduct surrounding her detention and death. At the time officials stated, “No one suffers reprisal for taking part in lawful activities or international mechanisms.” More recently some have suggested Cao was a criminal who was being prosecuted according to the law, or questioned whether she was a human rights defender.

In the Human Rights Council session immediately following Cao’s death, Chinese diplomats resorted to procedural tactics to block NGOs in Geneva from observing a moment of silence at the Council on the occasion of her death. Many observers noted that a state which sought to silence one of its most prominent human rights defenders then tried to stop other defenders to honor her memory with silence.

[…] “One of the Council’s greatest challenges is in holding all member states to account, including powerful governments like China’s,” said Richardson. “The Human Rights Council has an institutional responsibility to address all cases of state reprisals against those engaging with UN mechanisms. The time is past due for China to account for its actions. The Council’s credibility is at stake.” [Source]

U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein opened the Council’s current session with a statement in which he expressed concern at China’s crackdown on rights lawyers and at proposed new laws to regulate NGOs. He also referred to its efforts to restrict civil society at the U.N. itself.

Instability is expensive. Conflict is expensive. Offering a space for the voices of civil society to air grievances, and work towards solutions, is free.

When ordinary people can share ideas to overcome common problems, the result is better, more healthy, more secure and more sustainable States. It is not treachery to identify gaps, and spotlight ugly truths that hold a country back from being more just and more inclusive. When States limit public freedoms and the independent voices of civic activity, they deny themselves the benefits of public engagement, and undermine national security, national prosperity and our collective progress. Civil society – enabled by the freedoms of expression, association and peaceful assembly – is a valuable partner, not a threat.

[…] Some Member States have sought to prevent civil society actors from working with UN human rights mechanisms, including this Council. Session after session, they attempt to bar from accreditation – based on spurious allegations of terrorist or criminal activity – groups that strive to expose problems and propose remedies. Reprisals have targeted some activists who have participated in Council-related activities, undermining the legitimacy and credibility of the international human rights institutions. [Source]

In July, Zeid warned of the “extraordinarily broad scope coupled with the vagueness of […] terminology and definitions” in China’s new national security law.