Rights defense lawyer Pu Zhiqiang was detained in May 2014 after he attended a private discussion of the Tiananmen protests. It was not until this May that he was indicted for “inciting ethnic hatred” and “causing a disturbance and provoking trouble.” In August, a request for pre-trial release was denied, and his trial was postponed for three months.

Journalist Jiang Xue has written a profile of Pu Zhiqiang’s wife, Meng Qun, for the Hong Kong-based journal Asia Weekly (亞洲週刊). CDT has translated the article in full, based on a version published online. Asia Weekly notes that slight revisions were made to the print edition. This article also appears on the Asia Weekly website under the title “17 Months of Torment for Pu Zhiqiang’s Wife Meng Qun.” An official media directive has been issued ordering its deletion from mainland websites.

A Year as a Wife

Jiang Xue

“Even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, […] and such illumination may well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given them on earth—this conviction is the inarticulate background against which these profiles were drawn. Eyes so used to darkness as ours will hardly be able to tell whether their light was the light of a candle or that of a blazing sun.”

—Hannah Arendt, “Men in Dark Times”

1

It is August 25. Clear skies, a hot day in Beijing. After leaving work at noon, Meng Qun grabs a quick meal in the hospital cafeteria, then rushes to catch the subway.

She carries a plastic bag containing a couple of undershirts and other clothes for her husband. In the course of her journey, she makes two subway transfers, exits at Shuangqiao Station, and then waits for a taxi. Sometimes she takes public transportation instead, riding a bus for eleven stops through the dusty Beijing suburbs where the city meets the countryside. Then she arrives in Dougezhuang.

The main entrance of the Beijing No. 1 Detention Center is well-concealed and lacks any signage. Outside the gray compound walls, there is a row of shrubbery which will turn a golden yellow in winter. She thinks it looks like “a mound of fire.” For now, there’s only an overgrowth of nameless wildflowers.

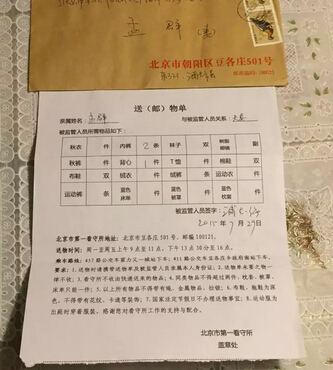

Every month, a standard request form for basic necessities is the only update she receives regarding her husband.

Meng Qun is 48 years old, a soft spoken physician with fair skin. Today she is wearing simple linen clothes and a pair of sneakers. Her only jewelry is a string of dark red prayer beads. She is a devout Buddhist.

From May 2014 to the present, it’s been fifteen months since she last saw her husband. The night before, she had just returned by train from her husband’s hometown in Luan County, Hebei, when she checked the mailbox and discovered her husband’s “letter” had arrived early. She was surprised and happy to the point of tears. You could call it a “letter,” but it’s actually nothing more than a standard monthly request form for basic necessities.

But this is enough to bring her comfort, and with the request form in hand, she has the justification to deliver clothes to her husband. Outside the detention center’s gray walls, she feels a bit closer to him.

Meng Qun is two years younger than her husband, and like him, she’s tall, five-foot-six. Her husband is nicknamed the “Giant Lawyer.” He is a chivalrous man. He was 49 years old when he welcomed the misfortune of this “practically predestined” prison time.

Over 40 years earlier, while Meng Qun was still in her mother’s belly, the Cultural Revolution was in full swing. When her father, a high school principal, was removed for investigation, her mother went to see him, on foot, shelling peanuts as she went. By the time she arrived, she had a bowl’s worth of peanuts, which she boiled for him to eat. Then she returned home.

When she was born, her father named her Meng Qun, saying that she should be part of the masses, the qunzhong, and nothing else. The Party pressed her father to change her name, but he didn’t, and she goes by Meng Qun to this day.

Now she is just like her mother was back then, making her way across the Beijing sprawl every month, going to a once unfamiliar place to see her husband.

2

On August 22, Meng Qun decided to take a trip to Luan County to see her husband’s relatives. On August 19, she had received the news of a three-month postponement of her husband’s trial.

She knows he can’t stop worrying. On the inside, he is thinking about his 89-year-old mother, his older brothers and sisters, his nieces and nephews, and his friends.

Every time she sends a message to him through the lawyers, she reiterates that everything is fine at home, don’t worry, staying healthy is the most important thing. But she knows that saying it over and over won’t help, so she went to check on his family for him.

She bought a train ticket for 4:50 a.m. on Saturday. On Friday night, she had arranged for a taxi to pick her up at 3:30 the next morning.

The stars were dim as the cab sped along Fourth Ring Road. Beijing was so quiet at that moment. She suddenly thought back to 26 years earlier, to that dawn in early summer. It was hot, dry, and windy that day, but at the same time, brutally cold.

They met in the square that year. He was at a sit-in with a group of students from the University of Political Science and Law, tall and large, impossible not to notice. She was studying medicine, in her fourth year at university, and interning at a hospital. She was an “angel in white” at the square. Word came that someone was sick, so she hurried over with the stretcher-carriers. The patient turned out to be him.

June arrived. That day, there was something strange in the atmosphere, but she still went to the square with a backpack full of books to review for her exams. She didn’t pay attention to anything other than the fact that the previous day he had asked her, “Are you still coming tomorrow?”

That dawn is etched on her memory: in the darkness, there were only flashes of cold light from the soldiers’ helmets…

She graduated and became a doctor. He received a strict warning from the school and then struggled to find work. Finally, Professor Jiang Ping arranged for him to be the manager’s secretary at the Dazhongsi Produce Market. On National Day, 1992, they wed.

Time flew by, and in an instant, all those years had passed. A friend said that after that year, a lot of people changed, but not Old Pu. Meng Qun believed that to be true. He had never changed. It was as if he was still that passionate young man, hurting and crying out for his country.

Over the years, he rushed around championing the cause of the common people. But she, despite earning a doctorate in medicine, became even more reserved, and did not concern herself with the turmoil of the world around her. Instead, she concentrated on family matters, looking after the young and the old. Except for that early summer day every year, when that she would go with him to the square to quietly honor that memory.

Their time together was little, their time together great, and middle age rushed in. Fate is like a giant wheel: no one can guess how it will turn. In May 2014, she was suddenly torn from her cozy home and thrust into history.

3

May 5, 2014 was the last time Meng Qun saw her husband before he lost his freedom.

At 11 p.m. the night before, she was already asleep when he came home. “National Security officers have asked me to tea. I’ll be out for a while,” he said, and he urged her to go back to sleep. But she couldn’t sleep. She turned on a reading lamp and waited for him. He finally returned after 2 a.m., explaining that he needed to get some clothing, because he might be gone for a few days.

As she watched his silhouette leave in the lamplight, she wasn’t overly anxious. “Drinking tea” was a regular occurrence, and “being travelled” was also normal. On National Day in 2010, the authorities forced Pu Zhiqiang to leave Beijing. No matter, he and Meng Qun, accompanied by police officers, toured Donglin Temple in Jiangxi and Jiuhua Mountain in Anhui. They made a sightseeing round, and she even dragged him to worship the Buddha.

Daybreak came, and she went to work. At midday, she received a text message from the police stating that they would come to her house in the afternoon and would require her cooperation.

She requested leave from work and rushed home. Downstairs, more than ten policemen were guarding her husband. In the elevator, he was cracking jokes with the neighbors, just like old times.

They searched their home for over two hours, carefully flipping through every item on the bookshelves. They confiscated a few books.

After 4 p.m., the search was complete. The police instructed her put together some clothing for Old Pu to take with him. Nothing with buttons, and no belts. She was flustered, and picked out a short-sleeved shirt with Ai Weiwei’s face on it. Annoyed, the police told her, “That won’t work.”

Finally, she pulled out their son’s school uniform: a pale yellow sweatshirt and track pants. Their son is even bigger than his father, so Pu could wear the uniform, though they wouldn’t fit well.

During a lull in the search, Pu said to Meng, “Don’t worry, I’ll probably be back very soon.” He urged her to take good care of herself. He also advised her that if she encountered any problems herself and needed a lawyer, she should turn to Zhang Sizhi and Gao Guangqing.

The police swarmed around him on the way downstairs. Meng carried the dog they had owned for over a decade as she walked him out and watched his large frame squeeze into the police car. She and the dog remained downstairs for a long time, staring off into the distance.

The next day, she received a phone call, requesting that she provide a signature acknowledging receipt of the notice of her husband’s detention.

4

The train arrives in Luan County at 7 a.m. This is a county town in the shadow of Tangshan. In 1976, over 200,000 lives were lost in the Tangshan Earthquake, and Luan County was almost entirely destroyed. That year, Old Pu was 11 years old. He and his adoptive parents left from the county town and went back to his biological parents’ village. It wasn’t until 1982, after he had graduated from Luan County Number One High School and tested into Nankai University that he truly left home.

Pu’s second oldest sister’s family is already waiting for her on the platform. As a boy, his father had sent him, the youngest son, to live with relatives. Even though they were not technically a family, blood is thicker than water, so how could those ties be severed? His second oldest sister asks Meng Qun, “Have you seen Zhiqiang lately?” Her eyes were full of worry.

About seven or eight kilometers away from the county town is Ligezhuang Village. On the road, big trucks boom by, and smoggy odors hang in the air. The county town is in Hebei’s flatlands. Steel mills and rock powder mills are everywhere. The economic development of the last few years has also brought environmental degradation.

The village is paved, but not well-planned. Buildings are scattered around haphazardly. The road back to the hillside is covered in sheep manure, and the thorny branches of red date trees extend out from the roadside. In the past, when they returned to his hometown, Pu would always take Meng up the hill to pick red dates and watch the trains go thundering past the village. In 1989, his adoptive father traveled across Tongzhou District to central Beijing, hoping to pull his son away from the square, but he did not succeed. In the summer vacation that followed, Pu, like many other university students at the time, fled back to his hometown and sought refuge on this desolate hillside.

Pu’s aging mother has been waiting by the door. The 89-year-old woman takes Meng Qun’s hand. Before she can speak, her withered eye sockets fill with tears for the son she had not seen in over a year.

Old Pu’s adoptive mother died in 2013. His adoptive father and biological father had passed away before then. All he has left on earth is his biological mother, so he especially cherishes and respects her.

Last May, when he was taken away, everyone kept the news from her. Then, one day, she heard his name on CCTV’s “Focus Report.” She knew something had happened to him.

Pu’s two older brothers arrive. The eldest is over 60, and has high blood pressure and heart disease. His health has deteriorated as he has worried about his little brother. “Have you seen Zhiqiang lately?” he asks. But he knows that only lawyers are permitted to see him, no family members. Meng Qun hasn’t seen her husband for 16 months.

No one blames him. His nephews are actually proud of him. One nephew, currently at university, says he didn’t realize he had such an impressive uncle until he learned about him online.

“But we don’t want him to be impressive. We just want him to be safe,” his eldest brother says in a muffled voice, smoking a cigarette and watching his mother wipe away a tear.

Meng Qun stays the night and returns to Beijing the next day. Before leaving, she places a string of prayer beads around his mother’s neck and tells her, “If you miss your son, pray to Buddha. Wait for him. Next time we’ll come back home together to see you.” Her calm seems to ease the family’s pain a bit.

5

On May 15 this year, Old Pu’s case entered the indictment phase. According to regulations, during this period it is not necessary for lawyers to apply for visitation privileges, but the detention center still put up obstacles. On June 2, his lawyer applied for visitation, but it wasn’t approved until June 23. After that point, it was unclear when another visit could be arranged.

Meng Qun was worried. She called the detention center. The person who answered said it was up to the leadership to decide. Meng Qun forced herself to hold her tongue. Disappointed, she hung up the phone, but not without first offering well wishes to the person on the other end.

On July 17, she went to the detention center to see the director. The director said that he answered to the next level of leadership and was not able to decide visitation times. “Who is that leadership?” she asked. But the director stayed silent.

On June 21, Meng Qun printed two copies of a complaint letter. Her friends told her to send it by express mail, not to go running around. She decided to make the trip anyway, because she feared that if she mailed the letter, the other side could claim to have not received it.

She asked for leave from work. She remembered how he had urged her not to take leave and allow her work to be affected, but now there is no other option. Fortunately, her colleagues are all kind-hearted and do their best to help her rearrange her schedule. She rarely went out before, and when she did go out, it was just back and forth between work and home. Now she has no choice but to run around everywhere. Before she left home to lodge her complaint, she looked up the address, phone number, and bus routes on the Internet and took pictures of them with her cell phone, so she could reference them at any point.

She began her journey at 1 p.m. After leaving the hospital, she took a bus to You’anmen. When she stepped off, she looked around, confused, unsure of where to go next. Online it clearly said to walk about 300 meters and arrive at Banbuqiao Road, but in recent years, Beijing has changed too much. Even though she’s a Beijing native, Meng Qun still has a hard time finding her way. She asked an old woman fanning herself by the road for directions, and she asked a vendor. Under the brilliant sun, heat waves rolled off the asphalt and mingled with the haze.

“I suddenly realized that even though he’s being held in detention, at least he doesn’t have run around, or endure this hellish sun and sticky haze. And then I felt much more relaxed.” That’s what she wrote in her journal that day.

She arrived at Compound 44. An imposing wall ran north to south. She saw a security guard and asked him who she should talk to regarding the detention center. The young guard looked perplexed. So she had to ask a policeman. And afterward, she heard the policeman berating the guard, “Why did you let her in without credentials?”

She walked another 20 minutes to the prison management center. She was greeted by the sight of a pretty policewoman. But the officer quickly told her, “We don’t oversee matters involving the detention center.”

In her 20-year career as a doctor, Meng Qun had become accustomed to birth, aging, illness, and death. She wasn’t particularly “literary”—most of her writing was medical records. But now, she began to write letters to her husband.

“When he’s released, I’ll show them to him so that he’ll know what I was thinking about all this time.”

6

Meng Qun has two cell phones. One is the old phone her husband gave her, and the other is an iPhone that Ai Weiwei gave her after her husband was detained. To convince her to accept the gift, Ai said she could give it to Old Pu to take photos. She had to accept it. She says that Old Pu has a lot of friends she didn’t know before, but who have taken care of her in Pu’s absence. Once, a stranger added money to her phone card. “I’m very grateful,” she says.

Not long ago, a famous philanthropist visited Meng Qun and said that she was surprised at the strength and calm that Meng Qun demonstrated. “She was completely lost in the beginning, but over the course of this year, she’s made tremendous progress,” the philanthropist said.

And it’s true. Right after her husband’s troubles began, Meng Qun was beside herself. Previously, she had paid very little attention to public affairs, but after her husband was detained, she paid attention to everything. When it came to dealing with public opinion, she was completely outside her area of expertise. In regard to what defensive strategy she should employ, her friends were completely at odds with each other, and she was at a loss.

And then there was the terror she felt deep down. She remembered being jittery that whole month as people were detained one after another. She was worried that she would also be taken away. The memory of her father being struggled against during the Cultural Revolution periodically flashed before her eyes. She couldn’t help thinking that all of this could happen to her as well.

She didn’t dare tell her parents. Only her younger brother was running around with her. In the midst of anxiety and worry, her brother had a cerebral hemorrhage at a gas station one day, and medical assistance arrived just in time to save him.

She was afraid to return to her empty home because someone had carelessly leaked her address online. All she could do was rotate between the homes of relatives. The worst part was, she herself began experiencing health problems. She was worried that she had cancer. Her greatest fear is that she will die before his release.

“The moment you were taken away by the police, I suddenly became illiterate. I had no choice but to begin ‘opening my eyes to the world,’ and ‘fight illiteracy’ for myself,” she wrote in a letter to her husband. Thus Meng Qun, who had been hiding in her husband’s shadow, uninvolved in public affairs, began her interaction with the state apparatus.

At first, she was always nervous. There was a time when the police went to search her brother’s house and ordered her to come. She rushed over in a panic and ended up at the wrong building.

When the police actually came to talk with her, it was because she had written an open letter to Xi Jinping about how Pu’s lawyer couldn’t guarantee his right to normal visits with his client. Two officers, a man and a woman, had a long talk with her, saying that “people would take advantage” of her, and if she had any issues she should go through normal channels to handle them. “So, if you’re the ‘normal channel’ from now on, can you leave a phone number?” she asked.

The second time the police arranged to talk with her, she was not in good spirits, and she “had a bad attitude toward them.” “Pu has confessed,” they said. She angrily replied, “First of all, Pu is innocent. Second, I trust that he will not die, and that he will come back.”

Still, the police are polite to her, calling her “Doctor Meng.” And she always adds her “best wishes” at the end of a phone call, regardless of whether she is speaking with friends or police.

7

It is faith that has sustained Meng Qun, enabling her to be calm and withstand the stress.

On June 20, 2014, there was already a warrant for her husband’s arrest. Everything was about to fall apart. She had previously arranged a trip with her spiritual mentor and fellow believers to go on a pilgrimage to Palpung Monastery in Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan.

Even though the situation was precarious, and she was apprehensive, she decided to go. In the end, she felt it was the right decision. Amid the peaceful Tibetan grasslands and the sacred and benevolent atmosphere of the monastery, she released the nightmares that had been entangling her, and understood that first and foremost, she must accept and face her circumstances.

Two days later, she hurried back to Beijing. She remembers the journey that night. The air was misty and the mountain roads were perilous. Her husband’s face appeared continuously before her eyes, and behind him, the benevolent face of Bodhisattva. She felt that it gave her strength.

Returning to Beijing, she says, there was much less fear in her heart. Although everything was still in turmoil, she slowly, gradually got back on track.

When she misses her husband, Meng Qun looks through old photographs. The only jewelry she wears is a string of dark red prayer beads.

“I’m slowly starting to understand that all these years he was taking the path of the bodhisattva, for the benefit of all,” she says. In April 2015, she wrote in an open letter to her husband, “Life is self-cultivation, to be a bodhisattva is to take on burdens… Through the strength of your vow of faith and the morality of your conduct, your suffering has illuminated the path before me.”

Just as before, she gives every person she meets a red or gold knot symbolizing good luck. When she goes to deliver clothing and other articles to her husband, she gives these knots to the policemen. Outside the entrance to the detention center, she gives them to the guards, too. Some people gaze at her indifferently, ignore the gesture, and walk away. Once, a pretty policewoman happily accepted the gift and thanked her.

Before, the majority of her WeChat friend circle was comprised of fellow Buddhists, and she would rarely forward “serious” messages. Now, her friend circle includes a lot of people who care about Old Pu, and she has started to forward messages that advocate for the wellbeing of the country and society.

“I believe that if these things are broadcast, people will see them, and people will be enlightened. I myself was enlightened by my WeChat circle,” she says.

She is no longer nervous when she sees police. She is gaining inner strength. “I’m no longer afraid of losing anything. Once, I told my spiritual mentor, even if I die now, I’ll still be a disciple of Buddha.”

Nevertheless, she is still suffering. Often, when she thinks of him, she starts to cry. She’ll think of the way life was before, when they rented a little one-story house in Beijing, and he borrowed a cart from the neighbors to go buy cabbage for the winter. Their son sat in the cart, and the sound of his laughter echoed down the alleyway.

She also thinks of 2009, when he led everyone back on the train from Deng Yujiao’s trial, and so many “fans” went to receive him at Beijing’s West Train Station. She hid in the crowd, taking pictures. Looking at him, “I felt joyous relief that he had emerged unharmed.”

She also remembers when the two of them watched the film “The Attorney” at home, and his eyes filled with tears. Hers did, too. She couldn’t help but say to him, “Actually, Chinese defense attorneys are even more impressive. They face even more hardship.”

These days, all she can do is urge him to read the scriptures, calm his mind, and take good care of his body. She worries that his 89-year-old mother won’t be able to hold on until he comes back. The dog that the family has owned for more than a decade is also old and might not survive until his return.

On August 18, she sent the Beijing Detention Center an application for “bail while awaiting trial,” requesting that Old Pu’s poor health be taken into consideration.

On August 31, Pu’s acting lawyer Shang Baojun received a phone call from the judge, who told Shang that the request for bail had not been approved because “Mr. Pu is still able to take care of himself, and so does not meet the requirements for bail.”

But Meng Qun never forgets to bring her national ID card every time she goes out. “You never know when they’ll tell me I can take him home.” [Chinese]

Translation by Heidi.