Just as the U.S. announced its “Clean Network” initiative and set a deadline for the video-sharing app TikTok to be bought by an American company or banned from the country, images, and screenshots have been circulating in China evincing TikTok parent company ByteDance’s coziness with the Chinese Communist Party. CDT Chinese editors have collected examples showing the ByteDance corporate Party Committee’s engagement in campaigns to “Pass Down Red Genes, Use Tech to Boost Patriotic Spirit” and “Find Descendants of Revolutionary Martyrs”:

“ByteDance Party Committee: Pass Down Red Genes, Use Tech to Boost Patriotic Spirit.”

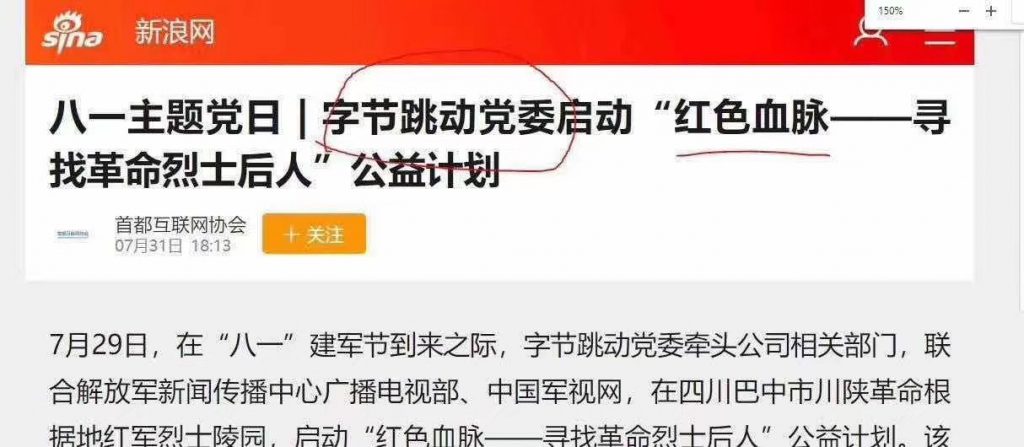

“ByteDance Party Committee Launches ‘Red Blood’ Charity Campaign to ‘Find Descendants of Revolutionary Martyrs’.”

ByteDance has been notably zealous in its efforts to appease the authorities after repeated run-ins in the past. In late 2017, the company ran into trouble with its news app Jinri Toutiao (“Today’s Headlines”), perturbing regional newspapers for sharing their content for free, and the Beijing internet regulators for “spreading pornographic and vulgar information.” Freedom House’s China Media Bulletin summarized the dust-up in its 2017 year in review:

While news content producers struggle, the news aggregation app Jinri Toutiao has enjoyed explosive growth. The app added 40 million users in 2017, bringing its total to 120 million. Parent company Beijing ByteDance is currently valued at $20 billion. Jinri Toutiao is not a journalistic enterprise: Run by well-remunerated engineers, it reposts content from other media outlets and provides a platform for bloggers to share and monetize their posts, using algorithms to tailor users’ feeds to their interests and often placing a slice of state-sanctioned news at the top of a large helping of fluff. But with success comes trouble. The company faces lawsuits from several online outlets and provincial newspapers, which claim that Jinri Toutiao has no right to share their content for free. Moreover, the government has chastised ByteDance on several occasions for sharing illegal content. Jinri Toutiao and similar apps are required to use a “super algorithm” to put stories about President Xi Jinping at the top of everyone’s feed and include “New Era”—Xi’s latest propaganda theme—as a news section, says [journalist and scholar] Fang Kecheng. [Source]

Jinri Toutiao quickly fell in line, removing fluff pieces, shutting down over 1,000 user accounts for sharing content that “may violate regulations,” and “updating” the app with a new focus on Xi Jinping’s “New Era.” In January 2018, the app started recruitment for 2,000 human censors. ByteDance got slammed again when its meme-sharing app Neihan Duanzi was shuttered in April 2018, further accelerating the company’s “red” transformation.

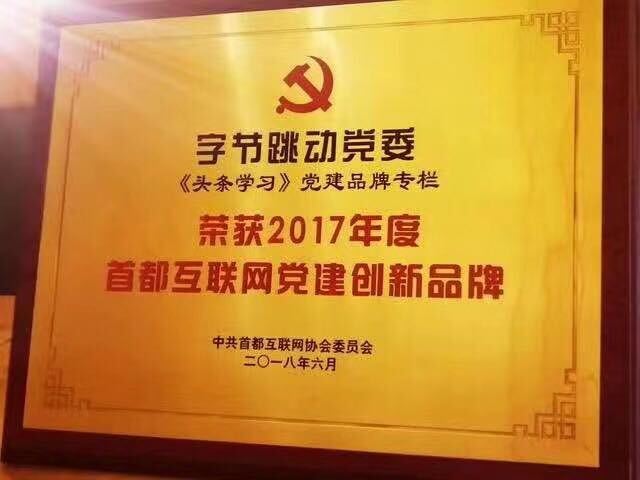

Plaque certifying ByteDance an “Innovative Brand of Internet Party Building.”

ByteDance has taken a new approach to censorship that has allowed it to flourish internationally while still upholding China’s “internet sovereignty.” Unlike Weibo or WeChat, TikTok and its Chinese equivalent, Douyin, are two separate apps:

One thing that’s been missing in the discussion of TikTok-ban:

China is actually the 1st country banning TikTok. To use TikTok instead of its CN version Douyin, u need vpn, an overseas App Store account and sometimes a foreign SIM card. Here’s a step-by-step tutorial on Zhihu. pic.twitter.com/5a36YltwhK

— Tony Lin 林東尼 (@tony_zy) August 8, 2020

2017 and 2018 witnessed a renewed emphasis on Party control and loyalty in the Chinese private sector, as guidelines to promote the “entrepreneurial spirit” (企业家精神) were rolled out ahead of the 19th Party Congress in 2017. Party-building is happening across the Chinese tech world:

Clockwise from top right: Staff at Tencent posing with the flag of the CCP; feting the new party-building branch at Weibo; Beijing Kuaishou Technology, creators of the Kuaishou video sharing app; e-commerce giant JD.com; Alibaba; ByteDance.

Tencent penguins in CCP kit.

See more evidence of the “red wave” in tech at CDT Chinese.