An end-of-year listicle created by China’s internet regulator, the Cyberspace Administration of China, is a time capsule of the Chinese Communist Party’s view on Chinese digital culture—what it wants people to read, watch, and do. The listicle is a round-up of online content most charged with “positive energy,” the CCP term for media imbued with the Party’s own values. Positive energy’s antithesis, “historical nihilism,” was the focus of another recent CAC ranking, a list of the ten most historically nihilist rumors. The CAC’s latest list, the “Five 100s,” ranks the top 100 pieces of content across five categories: “Positive Energy Writing,” “Positive Energy Pictures,” “Positive Energy Generators,” “Positive Energy-themed Activities,” and “Positive Energy Videos.” Unable to limit itself to a mere 500 paens to the Party, the CAC appended 50 “alternates” to the bottom of the list.

The ten best pieces of “positive energy,” as designated by the CAC, are nearly all dedicated to a single man—Xi Jinping:

Writing:

1. “Ten Details That Allow You To Feel Xi’s Original Aspiration”

2. “Xi Jinping and His Father: Two Generations of Communists ‘Pass the Baton’”Pictures:

1. “Xi’s Most Treasured Embroidered Bag”

2. “Altruism: ‘Elephant Chasers’ Share Beautiful Photos of Wild Asian Elephant Herd!”Generators:

1. Xinhua’s “Time to Study Xi” Management Team

2. People’s Liberation Army Daily Weibo Account Management TeamActivities:

1. Finding Martyrs’ Relatives

2. 100-part Mini-docuseries “Unsung Contributions”Videos:

1. “I, I am China”

2. “Minning Town”

The “Five 100s” seem designed to further build a cult of personality around Xi in the lead-up to this year’s 20th Party Congress, during which he is expected to claim a third term in power. Some items on the list center on Xi’s family. On The New York Times’ Sinosphere blog, Chris Buckley wrote that “Ancestor veneration in China is back,” describing the elaborate festivities surrounding the 100th anniversary of Xi’s father’s birth. Xi’s most treasured bag has the words “a mother’s love” embroidered on it. Xi brought the bag, a gift from his mother, with him to the countryside, where he was exiled during the Cultural Revolution. (His mother was earlier forced to denounce him during a struggle session.)

The greatest generator of “positive energy” was the team behind Xinhua’s “Time to Study Xi” webpage. The page is a veritable shrine to Xi. It includes his quotes, his speeches, a calendar dedicated to his activities, and even a “Jinping Style” section, which was once plastered with photos of Xi but seems to have been retired in favor of a video channel under the same name. Although Xi is known for “sartorial iconoclasm,” all such statements are relative—he is often seen wearing a conservative anorak. The People’s Liberation Army Daily Weibo Account, the runner up in the “generator” category, is the only account from which Xi Jinping is known to have sent a Weibo post. In 2015, while on an inspection of the newspaper’s facilities, Xi posted on Weibo wishing the troops a happy New Year.

Other “generators” honored for their contributions to positive energy include Wuheqilin and Hu Xijin, ranked tenth and eleventh, respectively. The former, the only unaffiliated individual in the top 40, is a nationalistic artist and illustrator who describes himself as being dedicated to “condemn[ing] American imperialism full-time.” The latter, now ex-editor of Global Times, was labeled “China’s troll king” by The Guardian.

The “Five 100s” activities section praised a group of self-professed patriots for their dedication to identifying the surviving relatives of Chinese soldiers martyred in past conflicts (22 such relatives have been found.) In February, police arrested seven people as part of an online campaign against slandering martyrs, and Chongqing police announced that they had engaged an eighth fugitive in “online pursuit.” The meaning of this bizarre phrase was never explained and the wanted suspect, a 19-year-old based outside of China, told Radio Free Asia: “I don’t know what this notice [of online pursuit] means.” Separately, after the journalist Luo Changping criticized the Korean War-inspired film “Battle for Lake Changjing,” China’s biggest box office hit of 2021, he was arrested by Beijing police for slandering martyrs.

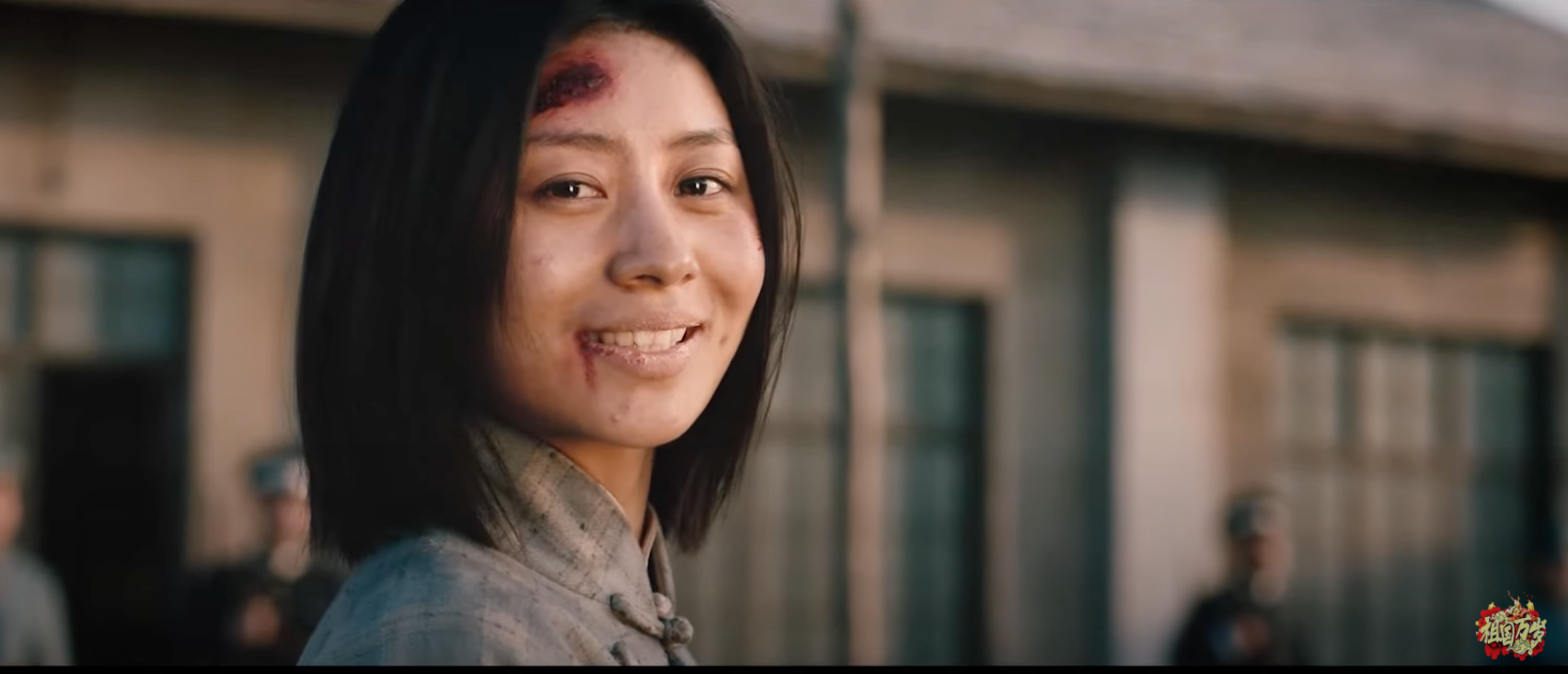

The top video, “I, I am China” also celebrates China’s martyrs as it traces the Party’s development from its founding to Xi’s ascension in just under two-and-a-half bewildering minutes. The short video includes a clip from the 2010 television series “Sister Jiang,” a dramatization of the novel “Red Crag,” which itself was based on the true story of Jiang Zhuyun, a guerilla fighter executed by the Nationalists in 1949. “I, I am China” features a bloodied Jiang smiling into the camera. A voiceover narrates, “Nobody can be young forever, but I can. For a young heart stays young forever,” as a gunshot sounds and Jiang’s open hand falls across the screen. A series of scenes from the Mao era follow: a clip of China’s first successful atomic bomb test and a nod to Jiao Yulu (Xi’s most beloved cadre of old). Disconcertingly, the video quickly switches to the present day: shots of two young people dancing in the street, a woman on an exercise bike, a clip of a Chinese esports team winning the League of Legends world championship (an accomplishment imperiled by new restrictions on youth gaming), and a member of the Chinese Women’s National Soccer Team scoring a goal (a World Cup championship is Xi’s other “Chinese Dream.”) The short features only two of China’s leaders: Mao and Xi. The second-best video was the iQiyi drama “Minning Town,” a “poverty alleviation drama” based on a program that Xi started while he was a provincial governor.

A still from “I, I am China” shows protagonist Sister Jiang smiling before her execution.

The list makes it clear that “positive energy” is synonymous with the promotion of Xi. The “Five 100s” is not the only year-end listicle the CAC has published. An article from the China Media Project delved into the CAC’s top ten keywords of 2021, a compilation of turgid phrases such as “celebrating the 100th anniversary of the CCP,” “Party history study and education,” and “6th Plenum of the 19th CCP Central Committee.” The contrast with CDT’s list of top ten censored words of 2021 could not be starker. Censorship, of course, is what the CAC does—in between posting listicles in praise of Xi.