A Shanghai resident’s defiant response to a local police officer’s warning that non-compliance with the city’s COVID policy would have a deleterious impact on the man’s future offspring went viral across Chinese social media—until it was censored. “After we punish you, it will influence your next three generations,” the officer, swaddled in full PPE, warned while standing in an apartment hallway. The man’s response, “We’re the last generation, thanks!”, has become a viral meme on the Chinese internet used to express despair about the state of the world and the country’s political trajectory.

In comments collected from across the internet, many connected the video to resonant events past and present, including: the chaining of Xiaohuamei, the 1989 student movement, and the One Child Policy:

zxzlaw:“We’re the last generation, thanks.” This phrase, redolent of tragedy, is an expression of the deepest form of despair. The speaker declared a decision of a biological nature: we will not reproduce. The decision is underpinned by a psychological and existential judgment: a future worth striving for has been taken from us. That phrase is, perhaps, the strongest indictment a young person can make of the era to which they belong. // The fact that he said it so calmly and matter-of-factly is precisely what makes it so shocking to listeners.

Leeing1992:Back in the day, I often heard people say, “Chinese people love children more than anyone on earth. Not even the One Child Policy can stop them. They’ll risk a huge fine just to have more kids.” Today, the phrase “We’re the last generation, thanks” is reverberating across the internet. No natalist policies can compare with the direct impact of their accelerationism.yamadarunzhi: [A couplet]

This world doesn’t want me

We’re the last generationXyczgmyx1:

1989: Because it’s my duty

2022: We’re the last generation, thanks

~ I’m weeping ~ [Chinese]

On Weibo, many shared memes derived from the phrase:

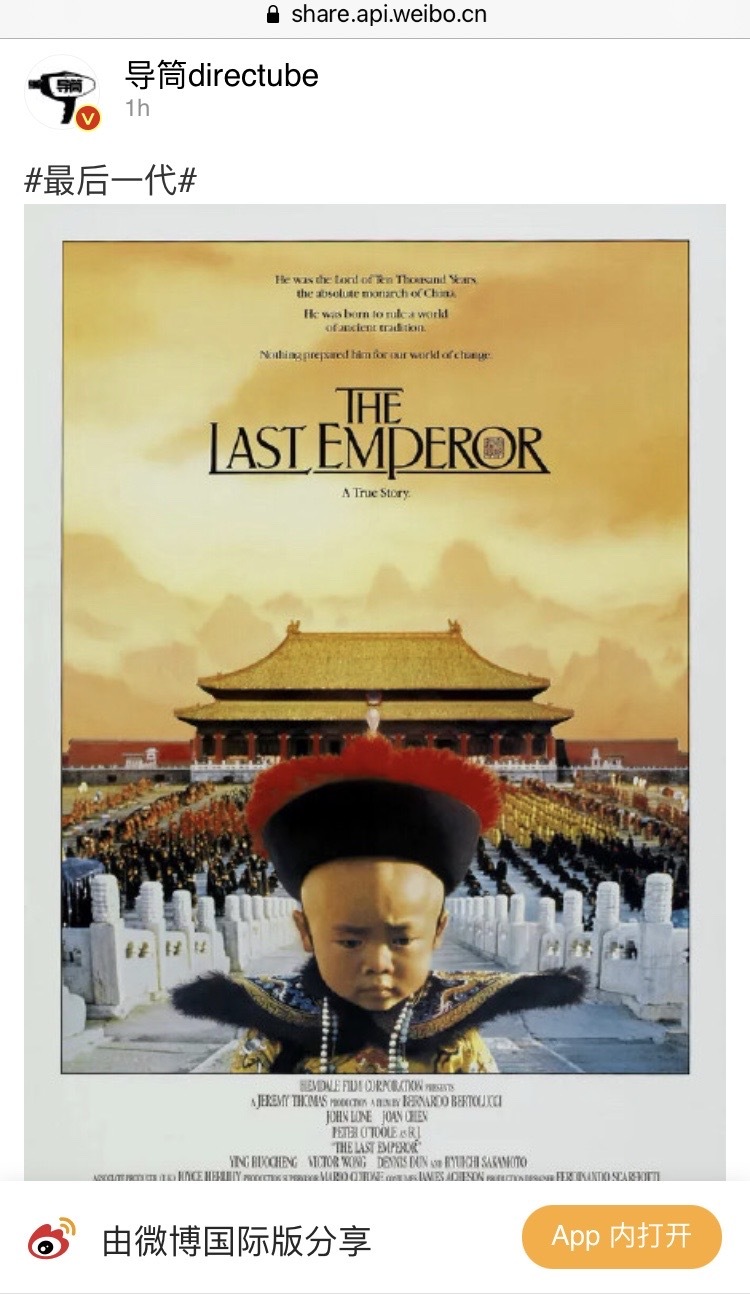

The popular film and social commentary account 导筒directube shared a film poster for the 1987 biographical drama about Puyi, the last Qing emperor, with the hashtag “last generation.”

One person handwrote the phrase on her t-shirt, which already bore the slogan “this is what a feminist looks like.”

Calligraphy reading: “A chive’s awakening: We’re the last generation.”

This meme, a screenshot from a dramatized biopic of the executed late-Qing reformer Tan Sitong, that has been circulating since at least 2018, shows his wife saying, “Fusheng [Tan Sitong’s courtesy name], we don’t have children yet,” and his response, “In today’s China, is it one more child or one more slave?” The meme originally circulated in response to news about a proposed “birth fund” to increase Chinese women’s’ fertility rate. [Chinese]

Censors quickly stepped in to erase discussion of the video. On Weibo searches for the hashtags “last generation” and “we’re the last generation, thanks!” returned a statement explaining the topic could not be displayed “due to relevant regulations and policies.” Memes like those shown above were also censored. WeChat essays touching on the phrase were also deleted. In defiance of the censorship, some Weibo users changed their usernames to variations on the “last generation” theme or wrote the phrase into their bios, both of which appear less subject to censorship.

The phrase was not simply sensitive for the context in which it emerged—opposition to Shanghai’s pandemic policy—but also for its inherent rejection of the Chinese state’s recent natalist push. In the face of a 30 percent drop in birth rates, the largest such decrease since the famine caused by the Great Leap Forward, the Chinese state has pushed a host of natalist policies: state-run matchmaking, a divorce cool-off period, abortion bans, real estate perks, and expanded maternity benefits. The state has also made gestures toward stronger protection of womens’ rights, but many remain skeptical: “As soon as they want access to your uterus, they start sweet-talking you.” In 2021, censors shut down Douban discussion groups where feminist adherents to the South Korean 6B4T tactic—which rejects heterosexual relationships and procreation—discussed their decision not to give birth. In Foreign Affairs, Carl Minzner warned that China, although in some respects well positioned to reverse the tide of falling birth rates, is doubling down on patriarchal values and political structures that dampen enthusiasm for more children, increasing the likelihood of “last generations”:

Xi seeks to steer China back to an earlier, more patriarchal era with respect to women. In early 2021, authorities published a compilation of his speeches on the family as part of an ongoing campaign to remold the party-led All-China Women’s Federation. In it, Xi extols family unity and invokes Chinese imperial precedent to praise “women’s special role” as “virtuous wives and good mothers, assisting their husbands and educating their children.”

Such calls are not merely rhetorical; they reflect a decisive shift in policy, as well. For example, the CCP is steadily turning against divorce. Scholars such as Xin He, Ke Li, and Ethan Michelson have documented that Chinese judges are increasingly unwilling to approve women’s requests to dissolve their marriages. In the early years of this century, Chinese courts approved 60 percent of divorce petitions. That has now declined to roughly 40 percent. Simultaneously, the percentage of divorce applications withdrawn by applicants has soared—from five percent in the late 1970s to over 25 percent today.

[…] Such trends could worsen yet further. Should authorities prioritize China’s demographic future as a political imperative under Xi, they might adopt explicit fertility targets and incorporate them into performance evaluation systems for local officials, fast-tracking the careers of those whose counties hit an annual TFR of 1.5. This is far from hypothetical. It is how Beijing managed anti-natalist population planning efforts during the decades of the one-child policy. [Source]

In a small move toward a more open system, Guangdong province last week confirmed that it had scrapped a number of onerous bureaucratic hurdles for new parents and single mothers. Expectant parents need no longer seek approval for births from state family planning offices, nor will they face restrictions on registering children, no matter how many they have. Children born outside of marriage will also be permitted to be registered, a major change. The province will also subsidize maternity leave for second and third children.