China’s not-so-new culture cops, now colloquially referred to as wenguan, have gone viral on Weibo amidst concerns over the perceived expansion of China’s police state. Earlier this year, the nationwide establishment of so-called nongguan, rural officers charged with policing agriculture, sparked anxiety over those agents’ perceived similarity to chengguan, urban officers with a notorious penchant for harassing street vendors, businesses, and journalists. All the above officers (cultural, agricultural, and urban) are officially called Comprehensive Administrative Law Enforcement agents. They are the street-level enforcers of the state’s law-and-order policies.

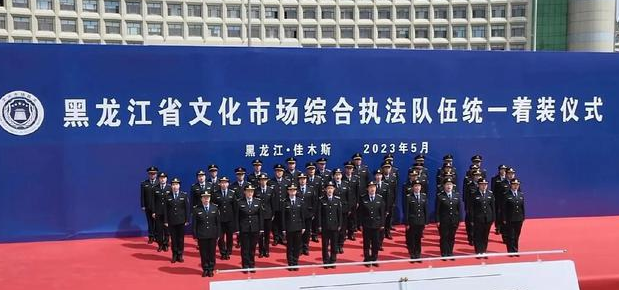

The discussion over wenguan was kicked off by an essay posted by WeChat account @开开眼界 (meaning “broaden your horizons” in English) about a Heilongjiang wenguan dress ceremony that took place in May:

The essay took pains to point out that wenguan are not actually new. Versions of the cultural law enforcement officers in their current form have existed since at least the 1990s. In recent weeks, however, they’ve re-entered the public eye—most famously for levying a $2 million dollar fine against a comedy studio for stand-up comedian Li Haosi’s joke comparing the PLA to his adopted dogs. (The performer was also blacklisted for life by a Party-affiliated artists’ association.)

Wenguan are tasked with ensuring that cultural productions are in tune with the “main melody,” Party-speak for orthodox political values. Specifically, they are tasked with defending the “Two Establishes”: (1) establishing Xi Jinping as the “core” of the Party, and (2) establishing Xi Jinping Thought as the guiding force of the New Era. A list of online services offered by the Beijing municipal wenguan ranges from investigations into improper medical product promotion in films and television shows to journalists conducting interviews without proper accreditation. Radio Free Asia interviewed Jiangsu commentator Zhang Jianping, who said the wenguan will “blindly inflict suffering” on the arts world:

“I think they will blindly inflict suffering. This type of strict control will cause China to lose its vibrancy. When a nation is no longer vibrant it will, as the slang goes, “no zuo no die.” We’ve all seen what happens when control is tightened—death. In the past when culture was allowed to flourish, as during the Hundred Flowers Campaign, there were no security risks, and no social unrest, either.” [Source]

In the wake of the Li Haosi incident, China’s culture police cracked down even on shows unrelated to the stand-up comic. At The New York Times, Vivian Wang documented the broader cultural crackdown, which appears to be in line with Xi’s directives that art conform to politics:

On Tuesday, Mr. Xi sent a letter to the National Art Museum of China for its 60th anniversary, reminding staff to “adhere to the correct political orientation.”[…] The frontman of a Buddhist-influenced Japanese chorus group, Kissaquo, said last Wednesday that his concert that night in the southern city of Guangzhou had been canceled. Hours later, the frontman, Kanho Yakushiji, said a performance in Hangzhou, in eastern China, had been canceled, too. And the next day, he announced that Beijing and Shanghai shows had also been called off.

[…] Stand-up show organizers did not return requests for comment. Several organizers of canceled musical performances denied that they had been told not to feature foreigners. An employee at a Nanjing music venue that canceled a tribute to the Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto said not enough tickets had been sold. […] But a foreign musician in Beijing, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, said his band was scheduled to play at a bar on Sunday and was told by the venue several days before that the gig was canceled because featuring foreigners would bring trouble. [Source]