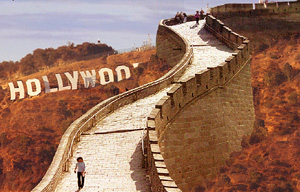

In recent years, the relationship between China and Hollywood has become increasingly symbiotic, as American film producers rely on the Chinese film market—now the second largest in the world—to turn a profit. According to Rob Cain of Forbes, half of the 12 Hollywood movies that attained the coveted “billion dollar box office mark” since 2011 would not have reached such sales numbers without Chinese moviegoers. The recent runaway success of “Warcraft” in China, after it floundered in U.S. box offices, led some to question whether the “future of film belongs to China.”

Hampered by import quotas which limit the number of foreign movies that can be distributed in China, Hollywood producers are increasingly co-producing with Chinese studios, a partnership that can take many forms and bring mixed results. Chinese investors and producers also look to Hollywood to help domestic movies gain a global audience, a struggle that has so far gained little fruit as international audiences have yet to warm to Chinese movies. Chinese investment in American movie studios and theaters, along with international studios’ efforts to gain access to the Chinese market, have all contributed to a creative environment where screenwriters and editors are careful not to include any content that may be offensive to the Chinese government. A recent example includes Marvel’s decision to recast the character of the Ancient One, originally a 500-year-old Tibetan sorcerer, with British actress Tilda Swinton in the role. Other recent Hollywood films have featured extraneous and sometimes out of place references to China or Chinese culture in an apparent effort to curry favor.

Michael Berry is a Professor of Asian Languages & Cultures at UCLA. He is the author of several books on Chinese film and literature, such as “Speaking in Images” and “A History of Pain,” and the translator of several novels, including “To Live” and “The Song of Everlasting Sorrow.” He is currently completing a book on the Chinese film industry, tentatively entitled Chinese Cinema with Hollywood Characteristics. He recently answered some questions from CDT about the increasingly powerful relationship between Hollywood and China, the logistics of co-production, and the resulting influence on the film industry in both countries. He notes how much this relationship has changed from just a decade ago, when China was an “afterthought” to Hollywood producers. “Today the two industries are so intricately intertwined that one cannot exist without the other,” he says.

China Digital Times: Domestic Chinese films have had little success attracting an international audience, and Beijing is presumably eager to use its burgeoning domestic film industry as a vehicle for soft power. What types of films are the majority of Chinese film-goers spending on? Why has there been such little foreign appeal for Chinese film productions? Is there any indication that Chinese producers are likely to see international demand grow?

China Digital Times: Domestic Chinese films have had little success attracting an international audience, and Beijing is presumably eager to use its burgeoning domestic film industry as a vehicle for soft power. What types of films are the majority of Chinese film-goers spending on? Why has there been such little foreign appeal for Chinese film productions? Is there any indication that Chinese producers are likely to see international demand grow?

Michael Berry: The Chinese film industry has seen exponential growth over the past several years. In 2010 the Chinese box office grew 61 percent to $1.47 billion, which already represented 61% growth over the previous year, but by 2015 box office receipts in China had reached $11 billion USD. In 2015 an average of 15 new screens were added per day in China, and 2016 estimates are in the neighborhood of 22 screens per day. With this kind of growth, Chinese audiences are spending and spending big on a variety of film experiences. The leading genres at the Chinese box office tend to be action-adventure films, historical fantasy films, romantic comedies, and action comedies. Two of the most recent blockbuster films in China “The Mermaid” and “Monster Hunt” are both good examples of the action/fantasy-comedy genre. Other smaller budget films that depict contemporary Chinese urban lifestyles, like the “Tiny Times” series, have also performed well.

In terms of foreign films, the quota system means that most international studios who gain access to the Chinese market will not take a chance on small budget indies, experimental films, or smaller productions. With only 34 slots per year, most studios stick with big budget commercial fare in the Chinese market. This means that the Hollywood (and other international) films that are distributed in China and do well with Chinese audiences tend to be big-budget spectacle films and A-list Blockbusters. These include action franchises like the “Transformers” series and superhero films “Iron Man” and “The Avengers.”

This has led to a somewhat unbalanced market in China. Whereas big budget studio films dominate box offices all over the world, in the Chinese market there is even less space devoted to smaller art house films. This is the result of a combination of factors, including the “side-effects” of the quota system, theatrical exhibition trends, audience tastes, and a lack of state support for independent films.

The reason for the lack of foreign interest in Chinese film productions is a tough nut to crack. I think a lot of people in the industry had hoped that the phenomenal success of “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” in international markets would have been the beginning of a new trend. But sixteen years later, “Crouching Tiger” still holds the box office record for the highest grossing foreign language film in U.S. box office history. No other Chinese-language film has been able to “crack the code” for producing another Chinese global blockbuster, although there have been many attempts. By contrast, Hollywood has been much more successful when it comes to producing films that play well to global audiences both east and west.

Of course this is a complex questions that gets into audience tastes, production quality of individual films, etc. but there is also the simple question of the “chicken and the egg”—are foreign audiences simply not interested in Chinese film or have foreign distribution companies simply already decided that foreign audiences aren’t interested and therefore fail to give those films the proper support when it comes to marketing, access to distribution and exhibition channels? To what degree are audience tastes shaping the market and to what degree are the existing infrastructures that have been developed and tweaked over several decades determining the rules of the game?

Future growth trends are always hard to predict. However, with the Chinese box office set to eclipse the U.S. box office sometime in 2017, there are many changes afoot that will inevitably make Chinese cinema more visible internationally. The Chinese firm Wanda not only owns AMC theaters, but with its 2016 acquisition of the Carmine Cinemas franchise, Wanda is now in control of the single largest movie theater chain in the world. With the rise of the China market, we don’t have to wait for “Chinese cinema to come to Hollywood” because “Hollywood is already going to China.” This can be seen not only through the proliferation of Sino-Hollywood co-productions, but also through the casting of Chinese A-listers in mainstream Hollywood films. At the same time, Chinese cinema is coming to Hollywood in other ways, with Chinese studios like Huayi Brothers, Wanda, and Alibaba heavily investing in Hollywood films.

CDT: More and more movies are being co-produced by U.S. and Chinese partners. Why are foreign studios increasingly involved in production deals with their Chinese counterparts? Is it just a fast track into the Chinese market, or are there other advantages?

MB: I would attribute the initial rise of U.S.-Chinese co-productions to the Chinese quota system. With the second largest film market in the world, the Chinese film market continues to enjoy unprecedented growth. However, the quota system, which dictates how many international films have access to theatrical release in China, has inhibited Hollywood’s access. As of 2016, the quota is 34 foreign films per year (which is up from 20, and 10 before that). With such a limited window for official foreign studios to gain access to the Chinese market, many studios began to explore alternative production models and the co-production has emerged as one of the most popular options, as co-production status provides a means for studios to circumvent the quota system.

CDT: What are the requirements for official co-production status?

MB: There have been many types of co-productions over the years that take on many forms; there are also different requirements for these different types of co-productions. Some qualify as “official co-productions” while others take on a more ambiguous identity. In a general sense, any film in which there is funding and collaboration between China and America are often referred to as “Sino-American co-productions” (Zhong Mei hepai pian). In this broad sense, some of the different categories might include: 1) Hollywood films that utilize Chinese studio space or exterior locations for shooting films that are thematically not related to China, (such as “Kill Bill” or “The Kite Runner”); 2) Hollywood films that incorporate Chinese themes, locations, and actors into the film in a more central way (“Forbidden Kingdom,” “The Karate Kid,” etc.); 3) Hollywood films that incorporate some token Chinese elements or supporting actors as a means to win “co-production status” (such as “Iron Man 3”); 4) Hollywood investing in films that otherwise look and feel like local Chinese films. These essentially function as a form of investment in the local Chinese film industry.

In 2004 the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) [since renamed as the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television] released a set of guidelines on co-productions, which outlined three types: 1) films in which investment and production are jointly handled by both sides; 2) Assisted productions in which foreign studios provide investment and their Chinese partners provide support in terms of equipment, locations and crew; and 3) Commissioned productions in which foreign studios commission their Chinese partners to produce content in China on their behalf. Over time, however, there has been a great deal of fluidity, ambiguity, and controversy as to what films qualify as a “co-production.” In some cases, films have been known to shift their status during the course of the production process, such as Ang Lee’s “Lust Caution,” which began as a co-production, lost it’s co-production status and moved shooting from Shanghai to Southeast Asia, and then was belatedly re-classified as a co-production status upon distribution. Other films such as “Looper,” “The Expendables 2,” and “Cloud Atlas” have also generated controversy in China when it comes to their “co-production” status.

One leading Chinese film importer I spoke with called the whole concept of the Sino-U.S. co-productions a “fake concept,” or a “pseudo-idea” due to the impossibility of finding a story that can truly work on both sides. He felt that due to a lack of shared history, each side is forced to compromise too heavily and therefore the very notion is flawed. But I think it is important to understand while a lot of people throw around the concept of Sino-U.S. or Sino-foreign co-productions, there are actually many types of collaboration happening between the Chinese film industry and international film companies. These collaborations take on many forms and official “co-productions” are just one facet of a much larger and more complex picture.

CDT: What’s the relationship between official co-production status and quota exemption?

MB: Of the three categories of co-production I outlined above as defined by SARFT, only the first category of co-productions, that is joint productions where both sides contribute investment and production support, qualify for quota exemption. If a film officially qualifies as a co-production it does not count among the 34 foreign films being distributed that year. This allows foreign studios and production companies to gain more access to the China market. For instance if 20th Century Fox has four films commercially distributed in China during a given year, but then also has two co-productions with Chinese studios, they can have a total of six films getting access to the China market. There are also differences in terms of how revenue sharing works and how box office profits are split, depending on whether a film is an import or a co-production. But at the same time, there is still a lot of tension between the logic of the free market and the political rules that are in place. Film exhibiters in China for instance would love to open up or do away with the quota system because of the need for more foreign content to fill their theaters.

CDT: Media reports have suggested that when the current revenue sharing agreement expires in 2017, China may allow more foreign films to market; some commentators have questioned the accuracy of this estimation. What is your take?

MB: I have heard talk from some industry insiders that China is planning on allowing more foreign films to market. While the whims of the party can be unpredictable, the general trend is certainly towards expansion. As more theaters and screens go up in China, there is an increasing demand for “product” to fill them with. While I do not see the end of protectionist policies aimed at guaranteeing a significant portion of Chinese screens be reserved for local films, it is hard to imagine a scenario where Hollywood access to this growing market would not incrementally increase over time, although the gains might still fall short of Hollywood studio expectations.

Current discussions about reforming the system also involve talk of allowing more foreign art house films into the market, which will be important for re-balancing the currently commercially dominated industry.

CDT: Recently, describing the government obstacles that had led to a seven-year delay in the U.S. theatrical release of “Shanghai,” Harvey Weinstein suggested that China’s current administration is more open to film producers: “Now, there’s a more open government, a more welcoming government, more welcoming to Americans wanting to do business over there.” How has the Xi administration made business easier for foreign film production?

MB: One big change is that just over a decade ago, the “China market” barely figured into most Hollywood studios’ thinking. China was an afterthought for Hollywood—neither side had much experience dealing with the other and their relationship was laden with misunderstandings, arrogance, and a general lack of engagement. Today the two industries are so intricately intertwined that one cannot exist without the other. Most Hollywood blockbusters need the Chinese market in order to make a profit. This is a fact that can be seen not only through co-productions and “Chinese elements” injected into films like “Transformers 4” or “Iron Man 3,” but also in casting choices, issues of cultural sensitivity when it comes to basic content approval. Whether or not a given blockbuster film gets the green light from a studio is now as much reliant on Chinese box office projections and how the film will play to Chinese audiences as it is to American ones. Take for example the Hollywood film “Warcraft,” which did not perform well in the U.S. market, but became a blockbuster in China and there is now talk of a sequel based entirely upon the film’s performance in the Chinese market. At the same time, Chinese studios and production company’s have increasingly made Hollywood’s business their business (recent “Hollywood” productions like “Southpaw,” “Hardcore Henry,” and “Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation” were all co-financed by Chinese production companies). So the ease of doing business works both ways. Part of the improvement in business relations also comes from Hollywood finally learning the rules of the game. No one is making films like “Red Corner” or “Kundun” anymore—films that the CCP would view as antagonistic—Hollywood studios have learned how to self-censor just as well as their Chinese film counterparts because they know how much is financially riding on maintaining a good relationship with their Chinese counterparts.