In response to mounting violence in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China, Beijing launched an “ultra-tough, unconventional” crackdown on terrorism last May, and recently extended it through the end of 2015. Despite increased security measures in Xinjiang, attacks have continued. Some point to increasingly repressive policies amid the crackdown—restrictions on religious dress and custom, harsh sentencings for moderate Uyghur activists, or increased regional censorship and surveillance, for example—as cause for the underlying tensions behind continuing violence. (In the regional capital of Urumqi, a ban on the Islamic veil went into effect on February 1, ironically, “World Hijab Day.” At ChinaFile, James Leibold and Timothy Grose explain how this could further incense the Uyghur community.)

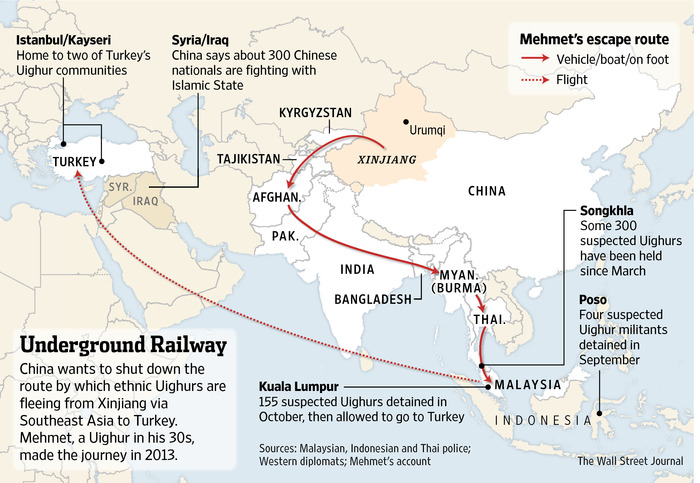

Chinese state media has continually alleged a tie between Xinjiang violence and the global jihad movement, and Uyghurs have long had difficulty procuring passports for international travel. Earlier this month, after two Uyghurs were shot by police while trying to flee to Vietnam, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced that a majority of the 800 people apprehended while trying to illegally enter Southeast Asia were doing so to access jihad training camps in the Middle East. Another potential motive for the desire to flee: to escape state policies in Xinjiang and eventually land in Turkey, a country long favorable to Uyghur refugees and populated by ethnic and linguistic kin. (Uyghurs detained in Thailand last year claimed to be Turkish, insisting as much when Chinese diplomats persuaded them to return to China.) At Al Jazeera, Sumeyye Ertekin talks to Uyghurs who found refuge from repressive policies and violence in Kayseri, Turkey after a long and perilous journey:

[…AB] explains why he left China: “There is no way we can live there anymore. My wife cannot cover her head. We cannot recite Quran, and even prayer is prohibited,” he said.

[…] Violent incidents, such as a deadly 2013 raid on a mosque during Ramadan, in which his 78-year-old uncle was killed, cemented his decision.

As for the story of his escape — an indirect route taken to avoid authorities — he said, “We walked in disguise for 28 days because Turkish Uighurs are not allowed to leave East Turkestan … After 28 days we arrived in Vietnam, where we met with the smugglers who helped us cross the forest area in six days, sometimes on foot and sometimes by car, till we arrived in Cambodia. From there we went to Laos, where we spent two days and then left for Thailand and stayed there for eight days, and again with the help of smugglers, we crossed into Malaysia in small boats at midnight.”

“We were accompanied by another family on the boat trip to Malaysia. They had a 5-year-old girl who fell from her mother’s lap into the sea. We couldn’t save her because none of us knew how to swim. Her mother’s cries are still ringing in my ears,” he said.

AB described the harsh conditions of the trip, saying that they could not carry large amounts of food, fearing it would impede their movement. Their diet consisted primarily of eggs and almonds, and when they were crossing the forest, they ate leaves and drank rainwater. […] [Source]

Recently, ten Turkish nationals were taken into custody in Shanghai for allegedly helping Uyghurs illegally emigrate from China.

A report from Jeremy Page and Emre Parker at the Wall Street Journal looks at a row between Beijing and Ankara over Turkey’s continued support for Uyghur refugees. The article also introduces Mehmet, a 30-year-old Uyghur who left for Turkey (via Southeast Asia) in 2013, and exemplifies both a desire to escape Beijing’s policies in Xinjiang and the willingness of some Uyghurs to resort to violence:

[…] He made no secret of wanting to resist Chinese rule. “If somebody gave me a gun, I would fight,” he said, sitting outside a Uighur activist center in the central-Turkish city of Kayseri. “China only gives us two options—either we must be exactly like them, or we will be destroyed.”

[…] After graduation, he joined a state-owned company—a coveted job in Xinjiang—but became disillusioned that few Uighurs were employed there. And he resented pressure to drink with prospective business partners, because Islam forbids alcohol consumption.

By the time of the 2009 Urumqi riots [see CDT coverage], he felt such pent-up anger that he joined the violence. He wouldn’t say what he did but said he was jailed for three years.

[…] Mehmet said he has spoken online with Uighurs in Turkey who want to join Islamic State but said he wants to head to Europe to work for the Uighur cause.

“Why would I risk my life fighting in Syria or Iraq?” he asked. “If I am going to fight, I want to fight for East Turkestan.” [Source]

For more on Turkey’s draw to would-be Uyghur refugees, see “5 Things to Know About Turkey and the Chinese Uighurs,” also from Jeremy Page and Emre Parker at the Wall Street Journal.

Regardless of the validity of Beijing’s claims that jihadist fomentation from abroad is a root cause for violent attacks in Xinjiang, avowed Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Bagdadhi has labeled China a nation threatening the rights of Muslims. In light of recent brutal killings by IS, Tea Leaf Nation’s David Wertime looks at netizen discussion around China’s role in combatting the militant group:

On Weibo, China’s massive microblogging platform, users are proving divided about whom to blame in the wake of the latest video. Many continued to echo longstanding mainstream media criticism of the United States; Obama “continues to swagger and fire off his mouth,” wrote one user, while another saw Western “meddling” and U.S. willingness to “spill blood to benefit economically” in the Middle East at the root of the problem. But many pushed back. One commenter wrote, “Today it’s a French person, or a Japanese person, or a Jordanian person; and tomorrow? Is it human life that matters, or giving the U.S. a ‘headache?’ If we too are to protect world piece, this is also a headache for us.” Another asked, “If one day ISIS kidnaps one of our own, what will we do? Besides angry online diatribes, we’re just sitting here waiting for a tragedy.”

Few comments urged action so directly. Rather than calling on China’s government to help, many web users repeatedly called on the U.N. or the world community to mobilize. In some popular comments, like the statement that “we must work together to lay siege” to IS, or the insistence that the five members of the Security Council “strike hard,” the critique of Chinese inaction was thinly veiled. Others seemed ignorant of ongoing efforts; one popular statement called on “the world to organize a coalition army” to attack IS, when in fact such a coalition was already organized in September 2014, comprising dozens of countries, with the U.S. at the helm. (China has offered help, but independent of that coalition, and it’s not clear whether it has followed up.) […] [Source]

Amid heightened tensions in Xinjiang and after officials in the similarly troubled Tibet Autonomous Region were “severely punished” for separatist activity, the South China Morning Post reports that hundreds of Xinjiang officials are being investigated for Party disloyalty. In a separate article, the SCMP notes that a rising CCTV Uyghur celebrity will be a guest host at the state broadcaster’s New Year Gala this year.