As rescue teams continue to search for survivors from the Oriental Star cruise ship, which sank in the Yangtze River on Monday evening, propaganda authorities have issued a directive banning journalists from reporting at the scene. According to official news reports, a cyclone caused the ship to capsize, but online some people are questioning whether human error could have been involved. The captain of the ship and the chief engineer are among only a handful of survivors, and they both have been taken into custody.

On WeChat, journalist Song Zhibiao published his reflections on the power of public opinion, and the reasons it is more difficult for authorities to control discussion of the accident now than it would have been ten years ago. Song is a former reporter for Southern Metropolis Daily who was transferred to a different publication after questioning the government’s role in the deaths of schoolchildren in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. He was later fired after writing for a Hong Kong website. He has since used his WeChat account to create “self-made media.”

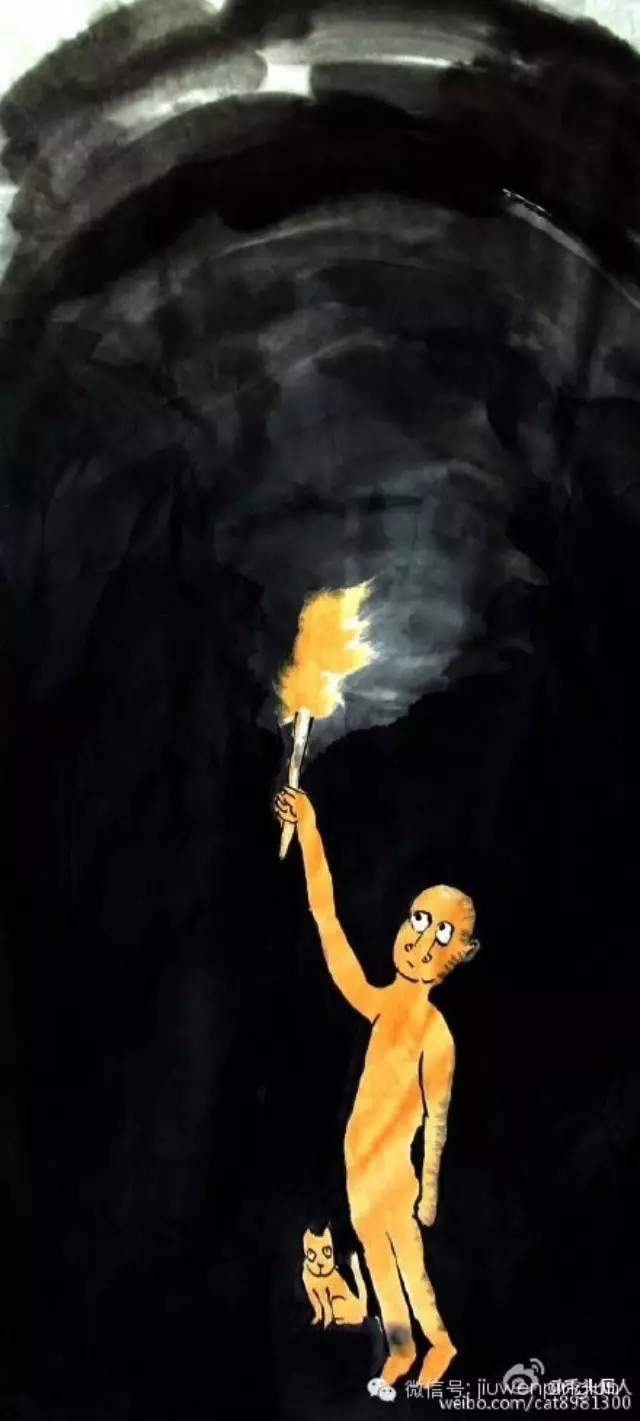

“The Torch” (Artist: Tutoujueren @秃头倔人)

The Captain Didn’t Die: A Synopsis of Public Opinion on the Shipwreck in Jianli

Song Zhibiao

The Oriental Star cruise ship sank carrying 458 people. The current situation is that Premier Li [Keqiang] went to the site of the accident, giving four words of instruction on his way there: heal wounds, provide oxygen. Off and on they’ve picked up ten some people out of the water, several of whom have since died. The rest are likely beyond saving. The apparent rescue team on the bank raised the red flag–right, why are they raising the red flag?

The authorities were not alerted until five hours after the incident. The captain avoided being pulled under the water. According to his own statement, he managed to swim to shore, abandoning more than 400 passengers under the pitch-black water. At present the only testimony regarding the sinking of the ship is the captain’s, who says that they ran into a tornado. And so we find ourselves at an impasse. With only this piece of evidence, we need more to confirm whether what he says is true or false.

The fact that the captain didn’t go down with the ship is itself a big problem, because his version of events immediately triggers the logic of stability maintenance, spreading information and certainty with monstrous speed. Early on the Hubei Daily was spreading rumors: It was the wind! It was a natural disaster! The unspoken message: It wasn’t human error! Less than ten hours after the accident, official Weibo accounts apologized again, making a despicably frivolous joke.

At some point the interns and junior analysts in charge of official Weibos posted a cartoonish, mocking essay, even “mainstream” according to insiders: a so-called new media “standard” text–more than four hundred lives, a question this important, and if you say it happened, then it happened. If you say it didn’t happen, then it didn’t happen. This kind of frivolous attitude is dangerous.

In order to preserve the rash conclusion that this was a “natural disaster and not human error,” the entire public opinion stability maintenance apparatus is once again putting on a performance on the waters of Jianli County. The relevant departments put out bans right away. No interviews allowed at the scene of accident, and recall reporters who have been dispatched. You can’t keep a list of names [of victims] either. Use Xinhua wire copy and CCTV images. In short, they want to control the shape of public opinion concerning the shipwreck.

And if this was ten years ago, these methods of cleaning up public opinion would have been effective. But with the ubiquitous social media of today, orders to clean up public opinion bring about negative consequences: the first is that they can control newspapers, but they can’t prohibit Weibo and WeChat; the second is that the order’s very existence has created an air of “untrustworthiness,” so people are even less willing to believe that this was a natural disaster and not human error. Otherwise, why would they issue a ban in the first place?

This method of managing information is decayed and it finds itself in an awkward place vis-a-vis public opinion today. Its air of enforcement is absolutely incapable of bringing about real enforcement, and it serves only to inspire reverse psychology and oppositional readings. This fact makes it clear that the path to prohibition relies on the passivity of control. Its outer ferocity and inner weakness cancel each other out. In truth, the discussions which have emerged on social media have gone far beyond conspiracy theories.

When people are allowed to discuss the possibility of a tornado without the impediment of a ban, then the National Meteorological Center might be “uncertain”; before the ban the media revealed the course of the sunken vessel, which changed direction direction several times, requiring an explanation; which is to say, the people were not nearly as angry as they became after the ban, but instead were searching for the real cause for the shipwreck. It makes restrictive management and control seem out of date.

When the news of the accident first emerged, people used to talking about current events on social media once again diverged from the conservative information management represented by the bans. These are two parallel dialogues, and the funny thing is that the latter group think they have a handle on information flow. It’s hard to say when it started, but the public discourse control apparatus is not only out of whack with the real discussion, it can’t even take part in it.

So, this is what the situation has become. Even if there is a ban to keep the traditional media in check (“traditional media” is more and more an immoral pejorative), public opinion is as usual forming around the incident. The ban presupposed a kind of “destructive force,” a kind of “sinister motive,” a kind of “untimely rage”–but none of these presuppositions have come to be. But according to the logic behind promoting the ban, they may show up in due time.

Note: A silent prayer for the people on the boat. Like the man in the title picture, if there is light, you can find the way. [Chinese]

Translation by Nick.