Lawmakers in Xinjiang this week passed the first region-wide legislation aiming to combat “religious extremism” in the violence-prone area, with a wide-ranging list of 15 types of behavior that as of April 1 will be banned. Reuters’ Christian Shepherd and Ben Blanchard report:

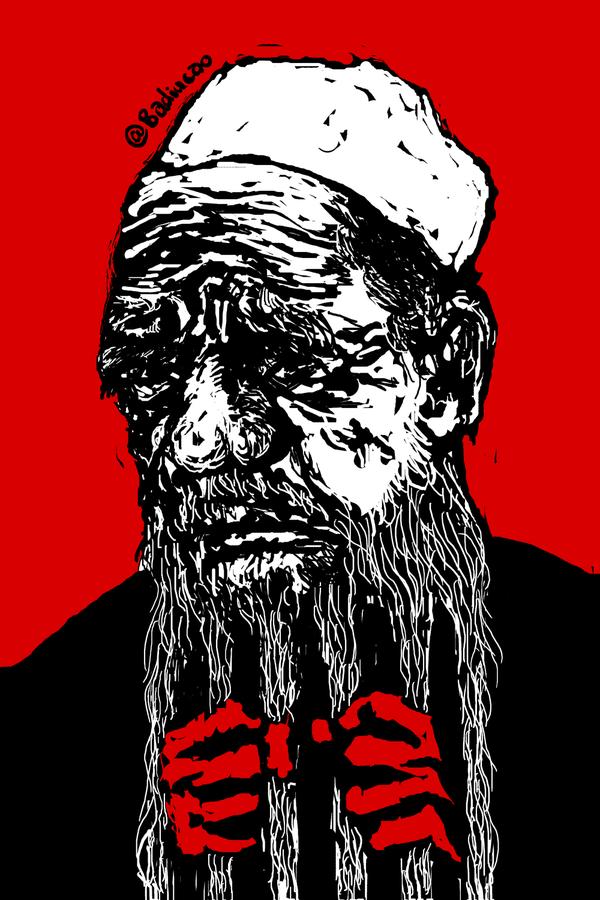

China will step up a campaign against religious extremism in the far western region of Xinjiang on Saturday by implementing a range of measures, including prohibiting “abnormal” beards, the wearing of veils in public places and the refusal to watch state television.

[…] Workers in public spaces like stations and airports will be required to “dissuade” those who fully cover their bodies, including veiling their faces, from entering, and to report them to the police, the rules state.

It will be banned to “reject or refuse radio, television and other public facilities and services”, marrying using religious rather than legal procedures and “using the name of Halal to meddle in the secular life of others”.

“Parents should use good moral conduct to influence their children, educate them to revere science, pursue culture, uphold ethnic unity and refuse and oppose extremism,” the rules say. […] [Source]

This new legislation comes amid an ongoing, steadily escalating, nationwide “people’s war on terror,” launched in 2014 in response to increasing incidents of violence in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China. The campaign has focused mainly on the Xinjiang region, and has recently included new surveillance and GPS tracking measures, massive military rallies (believed by some to be an attempt by Xinjiang Party chief Chen Quanguo to increase his chances at national level promotion later this year), and a hardening of top level anti-terror rhetoric that included President Xi’s call for a “great wall of iron” around Xinjiang.

On Twitter, Amnesty International’s William Nee commented on the new legislation in context of the ongoing crackdown:

Appears to be the broadest attempt yet to legitimize sweeping violations of freedom of religion & expression in XUAR https://t.co/GNw5FT6BnJ

— William Nee (@williamnee) March 30, 2017

Amid the long-running campaign, individual localities within Xinjiang have earlier enacted bans on some of the religious behaviors on the new list, such as wearing long beards or Islamic face-coverings. The new rules will significantly expand the forbidden behaviors and apply them across the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR). Coverage of the newly passed rules from the South China Morning Post’s Nectar Gan cites Xinjiang expert James Leibold who warns that the expansion of the restrictions on Uyghur religiosity could backfire against authorities:

James Leibold, an expert on China’s ethnic issues at La Trobe University in Australia, said the law was part of a broader trend aimed at legislating the government’s existing practices in the region. Some local officials had been enforcing many of the law’s restrictions for years, but adherence and enforcement had been patchy, Leibold said.

“By creating a [region] wide regulation, the new regime of Xinjiang party secretary Chen Quanguo is seeking to strengthen [Communist Party] control and root out any acts of non-compliance,” he said. “In the process, however, many aspects of Uygur cultural and religious life are now being deemed ‘abnormal’ and ‘manifestations’ of extremism, and thus subject to punitive enforcement.”

Leibold warned that forcefully imposing Han-defined norms on the Uygurs was likely to “increase their sense of cultural insecurity and thus ultimately undermine the party-state’s attempts to create a more social cohesive and stable society in Xinjiang.” [Source]

Uyghurs in Xinjiang have traditionally observed a moderate form of Sunni Islam. In recent years, conservative practices such as full-face veils have increased, which some see as a subversive response to the increasing state regulation of Uyghur’s religious observance.

Early in the “people’s” anti-terror campaign, moderate Uyghur intellectual Ilham Tohti was handed a surprisingly harsh life sentence for separatism, another official move that drew criticism for its potential to further enflame ethnic tensions in Xinjiang. Ilham Tohti’s U.S.-based daughter Jewher Ilham, who has been ceaselessly lobbying on behalf of her father since his sentencing, earlier this month spoke with Radio Free Asia. In the newly published interview, she expressed optimism that her father would not spend the rest of his life in prison, and hope that that Beijing would realize the mistake of the harsh sentence:

RFA: What do you say to your father in jail, assuming he will somehow be able to hear this?

Ilham: Hang in there. You’ll be out. You know it, right?

RFA: And what would you say to the Chinese government?

Ilham: Too many things that they’re not going to want to hear. To the Chinese government: I don’t think you really think my dad did something wrong. I know you might need somebody to stay in there and it happened that you chose my dad. I hope you can realize that it was a big mistake to lock him up and please release him. You will not regret it. [Source]

Beijing has received a steady stream of criticism for exacerbating the spread of extremism in Xinjiang with its harsh policies in the region, and Beijing has regularly dismissed such claims and denied the imposition of ethnic or religious persecution—as the Foreign Ministry did following the announcement of the new restrictions yesterday. At the East Asia Forum, Michael Clark suggests that the rapid reinforcement of Xinjiang’s security state has similarly allowed for the internationalization of Uyghur terrorism—a self-fulfilling prophecy of sort, as Beijing has long claimed a connection between Xinjiang violence and the global jihad movement. A propaganda video released last month by the Islamic State featured militant Uyghurs threatening to return to China to “shed blood like rivers and avenge the oppressed.”

The juxtaposition of these three events [the IS video, the recent military rallies in Xinjiang cities, and the February Pishan attack] suggests that Uyghur terrorism is now a trans-national challenge for Beijing. Ironically, this may in fact be a product of China’s own actions with respect to Xinjiang.

Xinjian[g]’s history of autonomy and geopolitical position astride the crossroads of Eurasia has always made Beijing vigilant about Xinjiang’s security and apt to respond with a heavy hand to the sporadic outbursts of anti-state violence and unrest. The region plays a key role in President Xi Jinping’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, making stability in Xinjiang a strategic imperative. President Xi asserted that ‘long term stability of the autonomous region is vital to the whole country’s reform, development and stability, as well as to national unity, ethnic harmony and national security’.

This has resulted not only in China’s focus on combating ‘terrorists’ through the kinetic means on display during February’s anti-terror rallies but also the development of a ‘security state’ in Xinjiang since the July 2009 Urumqi riots. […]

[…] Post-9/11, China has also consistently blamed two externally-based militant groups — the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM) and Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) — for attacks in Xinjiang. […]

But since the outbreak of the Syrian crisis TIP’s capabilities have grown. As Al Qaeda itself developed a presence in Syria from 2012, so too did TIP. TIP now has a well-documented presence on the Syrian battlefield, fighting alongside Al Qaeda’s affiliates. […] [Source]

Read more about Xinjiang and global jihad, via CDT. See also Fei Chang Dao’s translation of a local Xinjiang court’s 2016 ruling to imprison Tian Weiguo for three years for “inciting ethnic hatred,” which cited his use of a virtual private network (VPN) to post details of Xinjiang violence on overseas websites. For more on the Great Firewall, or the comparatively tight information controls in Xinjiang, see prior CDT coverage.