The below essay is a translation of WeChat blogger “Brother Lou’s” account of being invited to “drink tea” after sending a Weibo post questioning the integrity of a local Zhejiang police department. The essay was censored by WeChat soon after it was posted to the site. In the post, Brother Lou revealed how the Zhejiang police department dispatched four officers across provincial boundaries to pressure him into deleting the offending Weibo post, while all the time denying that was the purpose of their visit. Brother Lou’s account is remarkably mundane, demonstrating how police used boredom, kindness, and pleas for Brother Lou’s understanding to coerce him into compliance. CDT has extensively covered Chinese police officers’ use of “drinking tea” to pressure people into silence. Brother Lou’s account joins those chronicles:

Hi everyone, I’m Brother Lou.

Today, I simply want to write on my experience being “invited to tea” a couple days ago. It was a “cross-provincial” tea drinking experience.

At 9pm on October 20th, 2022, I received a surprise call from a local police officer. He said he was waiting for me in my apartment complex building manager’s office. He wanted me to come down for a bit, as he had a matter to discuss with me.

I immediately felt uneasy. So I asked him: are Zhejiang police looking for me?

The local officer immediately denied that, saying: “It’s not the Zhejiang police. We’re just looking to understand what’s going on.”

I didn’t want them to come up to the apartment looking for me as my kids were home and hadn’t gone to bed yet. I agreed to head down right away.

Just as I expected, the ones looking “to understand what’s going on” were police from Zhejiang. They were already waiting for me in the building manager’s office.

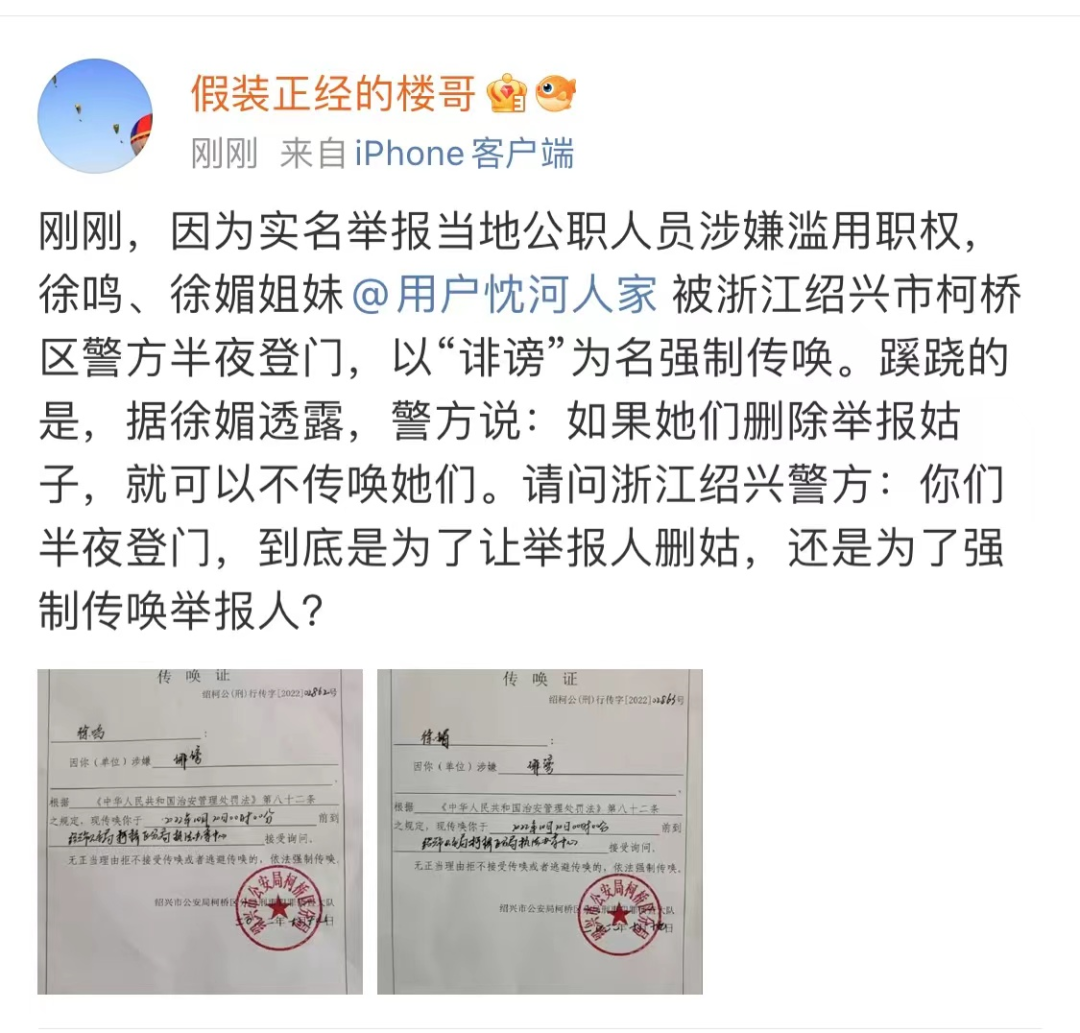

They’d come all the way from Zhejiang looking for me because of a Weibo post I’d sent that morning at 1:45am that called into question [the actions of] the police in Shaoxing, Zhejiang. [Screenshot below]

A screenshot of the Weibo post accusing Shaoxing police of harassing two sisters for filing a report on government officials’ misconduct. The screenshot shows two official summons and asks, “Shaoxing police: Why did you knock on their door in the middle of the night? Was it to force them to delete their report or was it to forcibly summon people who report officials?

The Shaoxing police dispatched four officers.

I asked the head officer: Why did you come all this way? To demand I delete that Weibo post?

He said they came without an agenda, that they came to chat with me—just shooting the breeze.

Afterwards, he began asking, in a methodical manner, about my family, marriage, children, parents, and ancestral home.

It’s fair to say that nobody has a deeper understanding of me and my family than that policeman, apart from myself.

I knew they hadn’t gone to such lengths to seek me out for a simple chat or a conversation on my life and goals, let alone to simply instruct me to treasure my currently blessed life.

So I again asked them directly: “Did you come here to demand I delete that Weibo post?”

He again refused to directly answer whether or not they wanted me to delete the Weibo post. He said, “As your post is just an interested party’s one-sided account, it might include false information. The summons you posted might have been a photoshopped fake.”

I said: “As to whether you called on [the sisters] in the middle of the night, I was on the phone with them while it happened and talked to the enforcing officers who confirmed to me that they were enforcing the summons. The document itself was sent to me by [the sisters] who took that photograph at the scene. As to [the sisters’] claim that “police demanded we delete our post reporting [the government officials],” [the sisters] have a recording.

My answer clearly put him on his heel, so he took a different tack: “Why did you help her post that Weibo? What’s your goal?”

I said: “First of all, freedom of speech is a fundamental right guaranteed to citizens in the Constitution. Secondly, superintendence is also a fundamental right guaranteed to citizens in the Constitution. I have no angle. Last December, after the pregnant Hunan teacher Li Tiantian was “mentally-illed” I wrote essays for seven days straight to help her out, until she was released back home. I’ve written essays on everything including this year’s ‘chained woman of Jiangsu‘ incident, last year’s ‘Zhengzhou floods,’ this year’s ‘Zhengzhou depositors‘ incident and even this year’s ‘Tangshan assault‘ incident. All of the people involved were unknown to me before I wrote those essays (apart from a couple of WeChat messages Li Tiantian and I had exchanged). If you must have a reason for why I write what I do, then I guess it’s that I hope my country can become ever better.”

Two of the officers then asked to see those other essays I’d written but I told them the accounts I used to publish them were all shut down. They’re inaccessible now.

I wasn’t pulling the wool over their eyes when I said that. It’s true. All of the public accounts I used to publish those essays were permanently shut down.

We went back and forth like this for about an hour when I told them I’d like to go home—I figured we’d covered everything already and was thinking of how late it was and my family members waiting for me at home. They instead informed me that they’d like to make an official record of the conversation at the station.

I told them we’d gone over everything there was to discuss, that there was no need to make an official record.

They said they’d come all this way and that when they got back they’d have to submit a report. They hoped I would understand.

I suggested we make an official record right there in the building manager’s office, but they said the office lacked the proper equipment, necessitating the trip to the police station.

Over WeChat I asked my friend, a lawyer, for his advice, after which I accompanied them in their car to the district police station.

At the station, we waited for about half-an-hour until a room to take the official report in became available. Two officers in charge of the report came in and asked the same questions I’d been asked in the building manager’s office.

It took nearly two hours to file the report because they asked for specific details—down to the time—that I’d written the essays and posted the Weibos, which required me to double check things to confirm them.

While I stepped out to go to the bathroom, an officer passed me in the hallways and whispered: “Can you delete the Weibo post?” He said the post’s reach and likes were steadily increasing and it was having a major negative impact.

I said: “We can take that up once this report is finished.”

Over WeChat, I asked my lawyer friend about whether or not I should delete my Weibo post. He advised me that I had the option to not delete it but that if I didn’t the police might waste more of my time and then suggested it would be best if I delete it in order to get home a bit sooner.

It was already one in the morning by then. My wife and kids, who had school the next day, had yet to sleep and were waiting for me to return home so I took my lawyer friend’s advice and, after finishing the report, I deleted the Weibo posts.

The entire “cross-provincial tea and conversation” took up five full hours. The four officers from Zhejiang were civil and polite the entire time and were proactive in purchasing me beverages, fruit, and an evening snack. I was also astonished by two of the officer’s well-informed views on history and literature.

By the time I got out of the police station, it was past two in the morning.

My wife had brought the children to the entrance of the police station, where they were waiting for me. I felt a swelling warmth but more than that, I felt guilty. [Chinese]