Late last month, a rash of food-stall, restaurant, shop, and factory closures in Chaozhou and Shantou, two prefectural-level cities in China’s southern Guangdong province, went viral online. Many Chinese social media users shared screenshots of rows of shuttered shops, some plastered with amusing closure signs: “Temporarily closed because our fish drowned,” read one, while another explained, “Closed today because the boss is in a bad mood.” A pair of signs on neighboring shops declared: “Closed ‘cause I’m scared of ghosts,” and “Closed because neighbor’s scared of ghosts, and now I am, too.”

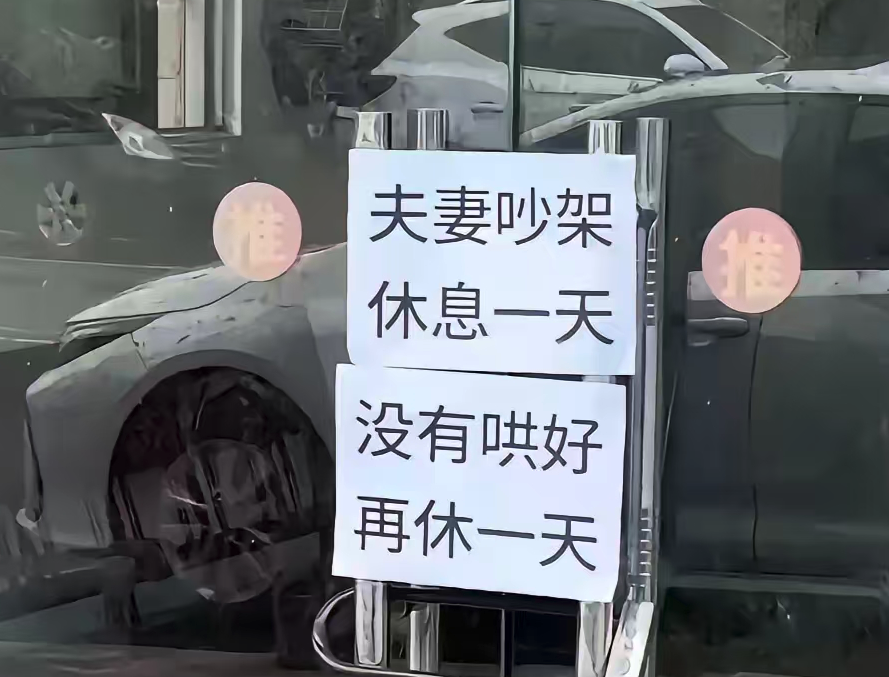

Two signs affixed to the door of a business read, “Closed today due to marital quarrel,” and “If we can’t make up, we’ll be closed tomorrow, too.” (source: WeChat account 正面连接, Zhèngmiàn liánjīe)

Fueled by online rumors of impending fire-, environmental-, and safety inspections and fears of potentially exorbitant fines for code violations, the closures only lasted for several days and were a minor inconvenience for local residents. But the phenomenon was indicative of a range of larger concerns, including a lack of transparency about safety inspections, fears of arbitrary or exploitatively high fines, economic anxieties among small business owners, and suspicions that cash-strapped localities are trying to boost revenues by putting the squeeze on local merchants. The superficially humorous closure signs posted by merchants belied these legitimate economic concerns, leading some netizens to term the mass business closures “a non-violent, non-cooperative movement for a new era.”

A screenshot of shuttered stores in Chaozhou, with the caption: “The citizens of Chaozhou are so compliant: overnight, all the shops and businesses have closed.” (source: WeChat account 晖常有道, Huī cháng yǒudào)

An article for RFA Mandarin by Qian Lang, translated by Luisetta Mudie, described the national-level inspections which led many business owners in Chaozhou and Shantou to decide to shut down for a few days, rather than risk being fined by overzealous inspection teams:

A nationwide inspection tour by ruling Communist Party officials threatening fines of up to 50,000 yuan, or nearly US$7,000, for safety violations has prompted a wave of business closures in at least two southern Chinese cities, according to social media reports.

Inspectors from China’s State Council have been touring the country in recent weeks in a bid to bring the nation’s lagging fire and workplace safety standards up to scratch, carrying [out] spot checks and under-cover investigations that could land business owners with a big fine.

[…] A legal professional from Guangdong who gave only the surname Chen for fear of reprisal said many see safety inspections as the government trying to boost revenues when local coffers are empty.

“It’s another way for them to raise money,” Chen said. “Yes, they want to eliminate safety hazards and maintain stability, but they also want to help local governments raise revenues.” [Source]

CDT editors compiled some of the many social media posts and comments from merchants and residents in Chaozhou and Shantou, explaining why they chose temporary closure over uncertainty and potential fines:

"They’re definitely doing inspections, random inspections, and there will be fines in the range of tens of thousands of yuan. I don’t want to get fined, so I decided to close up shop. If I’m hit with a fine, it’ll take a long time to make up for that loss, so I figure I might as well take a little break. Also, this time around the inspection teams are being sent by the State Council, which is a really big deal—who’d want to risk it? I’d rather stay closed than risk getting fined."

"I assume you’ve heard about what’s happening in Chaozhou. The government is going to conduct large-scale fire-safety and environmental inspections. These are blanket-style, comprehensive inspections, and businesses that aren’t up to code will have to close down until they’re in compliance, and could also face fines of 50,000 yuan. That’s why all the businesses, stores, and shops in Chaozhou have decided to shut down …"

"If we close shop for three days, we’ll lose 2,000 yuan, but if we open the shop for inspection, we risk being fined 50,000 yuan."

[…] Some netizens noticed that after #Online Rumors Spark Wave of Business Closures in Guangdong’s Chaozhou and Shantou" became a hot search topic on Weibo, it was quickly throttled by authorities, and many related news reports were deleted from various online platforms. [Chinese]

The role of rumors in driving the business closures was also key. In China’s increasingly opaque information environment, many citizens are more inclined to believe rumors spread via WeChat and other social media than to believe pronouncements made by government officials or state-media outlets. Despite periodic crackdowns on online “rumor-mongering” and administrative punishments (such as fines) meted out for spreading even the most innocuous of rumors—expressing gloomy sentiments about the economy, for example, or claiming that it was snowing in Xi’an when in fact, it was not—Chinese netizens remain undeterred. In many cases, online information that the government labeled and punished as “unfounded rumors” later turned out to be true, such as information about the nascent coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan in 2020; reports of food shortages and suffering of residents in Ili, Xinjiang and Shanghai during pandemic lockdowns in early- and mid-2022; and predictions that the government would abandon the nationwide “zero-COVID” policy in late 2022.

In a now-censored longform article published by the WeChat account 正面连接 (Zhèngmiàn liánjiē, "Positive Connections"), journalist Li Jielin explored the role of rumors in prompting shop closures, the punishments meted out to supposed “rumor-mongers” by local law enforcement, and the pandemic origins of why many Chinese citizens—including residents of Chaozhou and Shantou—no longer trust government authorities or state-media outlets when they claim certain widely shared rumors aren’t true:

As news of the fines spread, the only response from government authorities were various denials. At noon on the 23rd, Chaozhou authorities told Poster News [a state-media news outlet based in Shandong province]: "Only a few businesses closed down, but they did so purely for their own reasons, not to evade inspections, and they are all now open for business as usual."

[…] On the evening of the 24th, the Chaozhou Public Security Bureau refuted some of the rumors (such as "was cited for violations and fined 38,000 yuan," and "a bakery was fined 50,000 yuan," among others), and announced that it had meted out administrative punishments to five individuals. There was also a man in Shantou who claimed in a WeChat group that a certain restaurant was fined tens of thousands of yuan. The claim was investigated by the Shantou Public Security Bureau and found to be untrue, and the man was given an administrative punishment.

On the 24th, the Chaozhou and Shantou Emergency Management Bureaus told [financial news outlet] Caixin that no companies had been fined during this latest round of national inspections.

But many people no longer believe these rumor-refuting official pronouncements. Under a Douyin video refuting rumors [about the inspections], the top comments were: "See? Problem solved." "What left the deepest impression on me were refutations of ‘rumors’ of an outbreak of pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan," and "That year, eight people were arrested in Wuhan [for spreading rumors]." [Chinese]

In an article published by WeChat account 水瓶纪元 (Shuǐpíng jìyuán, WeChat ID: Aquarius-Age), journalist Jing Xun traveled to Shantou to interview local residents and business owners about the closures. The interviews reveal the uncertainty that many small merchants face, and a deeper economic malaise:

In a small park, a woman who sells local specialty products spoke to me about the fire-safety inspections. She said she had just re-opened her shop today (the 27th). Two days ago, she saw the online news about fines being levied in Chaozhou, and even though she wasn’t sure whether it was true or not, she decided to close her shop anyway. Despite the fact that her shop is fully equipped with fire-safety equipment, and the park—as a local tourist attraction—has special management personnel who conduct regular safety inspections, she was still worried: "Mainly because I’ve heard this inspection is different from the usual inspections. Online, people are saying the inspectors will definitely manage to dig up some [obscure] violations."

[…] The "national inspection" has become a popular conversation-opener for folks in Shantou these days. Wherever I go, I always end up talking to people about the national inspection, whether they bring up the topic or I do. The reasons merchants give for closing up shop are always more or less the same: fear of stiff fines, fear of the inevitability of being fined, and the sense that "everyone else is closing shop, so I will, too." It also seems that the merchants subject to inspection were not informed of the process or criteria involved: in other words, a lack of transparency about the inspections and lack of trust in the inspectors are also among the reasons why merchants decided to close their shops.

[…] Is the wave of shop closures real or not? Officials and the public have differing opinions

[…] On November 25, the Chaozhou Internet Police reported that five people had been punished for spreading rumors about topics such as shops being fined and shut down for code violations. The report reads: "In recent days, the Chaozhou Municipal Public Security Bureau has investigated and found that individuals surnamed Xie, Zhang, Su, Cai, and Dai had posted unverified or rumor-mongering news and comments online, including "was cited for violations and fined 38,000 yuan," "a bakery was fined 50,000 yuan," "an old man selling pig’s trotters was only fined 5,000 yuan," and "a factory here was fined 50 [meaning 50,000 yuan] and a noodle soup was fined 6 [meaning 6,000 yuan]." The above-mentioned individuals were given administrative punishments in accordance with the Public Security Administration Punishments Law.

Guangdong’s official media also seems to have begun trying to assuage public opinion through "positive energy" news reports. Reporters from Nanfang+ published articles in which interviewees denied that there had been any shop closures or fines.

[…] During my several days in Shantou, I also discovered some rather odd things. One day when we were taking a bus, the driver suddenly turned to us and said, "Did you know that bus drivers here haven’t been paid for three months?" The friend sitting next to me squeezed my arm nervously and whispered, "Isn’t that really dangerous? What if an [unpaid] bus driver gets upset and … does something?"

At first, I didn’t take the bus driver’s story seriously, but I heard the same story again when I was eating at a food stall. Another local friend told me that it was an open secret. "Nowadays when we go out," she said, "we don’t dare talk back to bus drivers." On some routes, drivers have [reportedly] replaced the bus payment QR codes with their personal WeChat QR payment codes, telling passengers, "They haven’t been paying us, you know."

My friend also conveyed another piece of news on a topic that locals have been discussing with great interest. This past autumn, the Shantou Municipal Bureau of Statistics […announced that] in the first three quarters of 2024, Shantou’s GDP was 227.93 billion yuan, a year-on-year decrease of 1.9% in real terms. […] This means that Shantou is the only one among five [of Guangdong’s] Special Economic Zones and the only city among Guangdong’s 21 cities with negative GDP growth. [Chinese]