The January 7th attack on the Paris-based satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo inspired an international wave of support for freedom of speech and of the press. Over the past week, however, China’s state media have repeatedly used the killings to call for limits on it. The Wall Street Journal’s Josh Chin highlighted a commentary by Xinhua’s Paris bureau chief Ying Qiang, for example:

“Charlie Hebdo had on multiple occasions been the target of protests and even revenge attacks on account of its controversial cartoons,” the Xinhua news agency commentary said, adding that the magazine had been criticized in the past for being “both crude and heartless” in its attacks on religion.

[…] “The content of the Xinhua commentary reflects Xinhua’s own point of view,” [foreign] ministry spokesman Hong Lei said, adding that China opposed terrorism in all forms.

“Many religions and ethnic groups in this world have their own totems and spiritual taboos. Mutual respect is crucial for peaceful coexistence,” the commentary said. “Unfettered and unprincipled satire, humiliation and free speech are not acceptable.”

The Chinese news agency isn’t alone in raising questions about the tenor of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons about Islam. Xinhua took note of this, quoting editorials in Western newspapers criticizing the French magazine’s approach and advocating greater respect for others’ religions and faiths. Still, none of the Western editorials it cited expressly advocated limiting freedom of speech. [Source]

Also at Xinhua, Liang Xizhi presented a very similar argument:

Any killings or violence related to terrorism should be condemned and the perpetrators be brought to justice. However, it is high time for the Western world to review the root causes of terrorism, as well as the limitation of press freedom, to avoid more violence in the future.

[…] The attacks against Charlie Hebdo should not be simplified as attacks on press freedom, for even the freedom itself has its limits, which does not include insulting, sneering or taunting other people’s religions or beliefs.

The world is diversified and every religion and culture has its own core values.

It is important to show respect for the differences of other peoples’ religious beliefs and cultures for the sake of peaceful coexistence in the world, rather than exercising unlimited, unprincipled satire, insult and press freedom without considering other peoples’ feelings. [Source]

Radio Free Asia pointed out two further examples:

“Westerners believe that when a small minority of Western media satirize the Islamic prophet, that this is ‘freedom of the press,’” [Global Times] said in an editorial on Friday.

“Some people even see the protection of this freedom a Western value.”

[T]he Global Times said many Muslims living in the West “feel that they are neither trusted nor respected.”

It said Western politicians were unwilling to “curb” media outlets because of their need to win votes. “Sometimes they even support the media,” the paper said.

While the official Xinhua news agency echoed the Chinese government’s condemnation of the attacks, it said they had highlighted “issues with France’s anti-terrorism and immigration policies in recent years.”

French involvement in strikes on Libya and the Islamic State had turned the country into a target for terrorists, while religious extremism has been allowed to flourish under the country’s liberal religious freedom policies, it said. [Source]

(State media articles advocating press restrictions missed the opportunity to argue that information controls might have dampened a wave of attacks on 26 French mosques with firebombs, guns, grenades, and pig heads.)

As Hong Lei said, these do not necessarily represent Beijing’s official position. Chinese ambassador Kong Quan’s appearance at a 1.6 million strong “unity march” in Paris was in any case no more ironic than the presence of many other foreign officials. Senegal banned Charlie Hebdo days after its president participated in the march. “We vomit on all these people who suddenly say they are our friends,” Charlie cartoonist Bernard Holtrop commented. Dozens of arrests of those felt to be condoning terrorism have also prompted questions about the limits of French authorities’ commitment to freedom of expression, which Jonathan Turley wrote at The Washington Post pose a more serious threat than terrorism.

Many French would concur with Global Times’ statement that some of the country’s Muslims feel “neither trusted not respected.” Film director Luc Besson, for example, expressed sympathy and support in an open letter posted in English at The Guardian:

[…] Let’s start at the beginning. What is the society we’re offering you today?

It’s based on money, profit, segregation and racism. In some suburbs, unemployment for people under 25 is 50%. You are marginalised because of your colour or your first name. You’re questioned 10 times a day, you’re crowded into apartment blocks and no one represents you. Who could live and thrive under such conditions? [Source]

Similar views came from French voices in The Guardian’s account of the attackers’ histories. At Mediapart, Olivier Tonneau attributed the susceptibility to radicalization of some young French Muslims primarily to “the complete failure of the Republic to deliver on its promises of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” A Friday New York Times article on this marginalization described many young Muslims who “totally feel cut off from France” as a result.

The Economist reported this week on a broadly similar predicament among China’s Uyghurs and Tibetans:

China is urbanising at a rapid pace. In 2000 nearly two-thirds of its residents lived in the countryside. Today fewer than half do. But two ethnic groups, whose members often chafe at Chinese rule, are bucking this trend. Uighurs and Tibetans are staying on the farm, often because discrimination against them makes it difficult to find work in cities. As ethnic discontent grows, so too does the discrimination, creating a vicious circle.

[…] Reza Hasmath of Oxford University found that minority candidates in Beijing, for example, were better educated on average than their Han counterparts, but got worse-paying jobs. A separate study found that CVs of Uighurs and Tibetans, whose ethnicities are clearly identifiable from their names (most Uighurs also look physically very different from Han Chinese), generated far fewer calls for interviews. [Source]

More on that: This 2012 paper found job applicants with Uighur & Tibetan names got far fewer calls for interviews http://t.co/ilAdsM2d2D

— Gady Epstein (@gadyepstein) January 16, 2015

Around the fourth anniversary of the deadly 2009 Urumqi riots in 2013, Hasmath described such socio-economic factors as “perhaps the most culpable factor behind current ethnic tensions” in Xinjiang. Another portion of the blame went to restrictions on religious practice, also in place to a lesser extent in France, despite Xinhua’s criticism of its excessively liberal religious freedom policies. From Matt Schiavenza at The New Republic:

[…] The French government famously restricts when and where French women can wear headscarves, a regulation that critics claim robs the country’s minority population of their identity. Likewise, the Chinese government has imposed similar restrictions on Islamic dress among its Uighur population, most recently by banning full-length burqas in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital city. The ban followed a similar restriction imposed in Karamay, a smaller Xinjiang city, that forbids religious wear on public transportation.

But China’s repression of its Uighur population goes well beyond similar French measures. Officials in Xinjiang have placed the Chinese flag inside mosques throughout the region, and have restricted many faithful (including children under the age of 18) from entering mosques at all. The Chinese government has also clamped down on bilingual education in the region, placing Uighur people—for whom Mandarin is not a first language—at a competitive disadvantage. “A lot of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, as in Tibet, feel that the Chinese government is practicing a form of cultural genocide,” said Julia Famularo, an expert in the region at Project 2049, a think tank in Washington, D.C. [Source]

Following last year’s deadly knife attack in Kunming, state media was in no mood to “review root causes,” as it prescribed for France. Xinhua’s Zhu Dongyang exclaimed that Western news sources’ “implicit accusations against China’s ethnic policy are […] baseless and biased. Beijing has fully demonstrated its commitment to protecting freedom of region [sic], preserving cultural diversity and promoting development and prosperity in minority areas.” Another commentary declared that “anyone attempting to harbor and provide sympathies for the terrorists, calling them the repressed or the weak, is encouraging such attacks and helping committing a crime.” Global Times reported similar positions from two Renmin University scholars, Jin Canrong—”This terror has just happened, and now is not the right time to dig into its causes”—and Wang Hongwei—”It must be noted that most terrorist actions are done out of irrationality or complete madness. […] The slaughter reflects no ethnic problems, but the vilest of crimes against humanity.”

New York University history professor Jonathan Zimmerman commented on the recent articles at the New York Daily News:

Let’s leave aside the fact that China — despite its strict censorship policies — has faced violent attacks from separatists in the predominantly Muslim western province of Xinjiang. The most cynical claim here is that free speech is a “Western” value, when many Chinese people are obviously clamoring for it.

And cartoonists have often led the charge. Consider Kuang Biao, whose account on Weibo — the popular Chinese micro-blogging network — was abruptly shut down by state authorities two years ago. One of Biao’s now-censored cartoons indicted censorship itself: Under the caption “Mainstream media,” he drew a caged bird with a pen in its beak.

Then there’s the artist who goes by the name Crazy Crab, whose cartoon series was banned in 2011. The series was called “Hexie,” which has since become a codeword for “being censored” among Chinese bloggers and cartoonists. [See a collection of responses to the Charlie Hebdo attack by Chinese cartoonists, and Crazy Crab’s work for CDT.]

[…] Even as China joins the global chorus against “terrorism,” its restrictions on freedom actually echo the terrorists who struck in Paris last week. Both of them insist that speech must be squelched in deference to a larger power. But whereas the terrorists invoke religion, threatening anyone who “blasphemes” it, the Chinese demand fealty to the state.

Charlie Hebdo didn’t just mock the fanaticism of the faithful, whatever their religion. It mocked the pretensions of the powerful, wherever they ruled. Too bad so many of them — in China, and around the world — can’t take the joke. [Source]

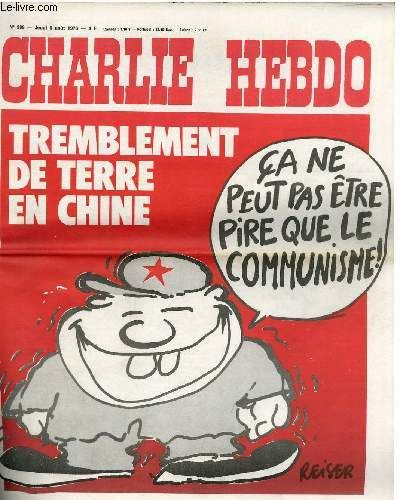

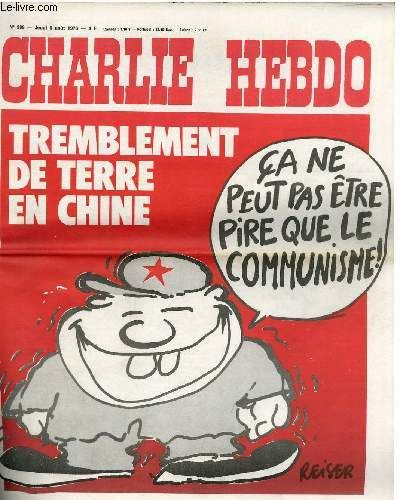

In Charlie Hebdo’s case, the joke has occasionally been aimed directly at Beijing. After the 1976 Tangshan Earthquake, which killed between 240,000 and 650,000 people, its cover proclaimed “it can’t be worse than Communism!”

The magazine did not leave depictions of racially stereotypical traits such as buck teeth behind in the 70s, as Abe Sauer pointed out on Twitter:

People who defend Charlie Hebdo as not at all racist have prob never seen some of mag's China coverage. Sample: pic.twitter.com/d1JHdElLTM

— Abe Sauer (@abesauer) January 13, 2015

For a range of perspectives on this side of the magazine’s material, see Olivier Tonneau’s previously mentioned letter, which claims that “Charlie Hebdo promoted equality, liberty and fraternity – they were part of the solution, not the problem”; the website Understanding Charlie Hebdo, which presents sympathetic explanations of several cartoons; former staffer Olivier Cyran’s accusation that “after September 11, Charlie Hebdo was among the first in the so-called leftist press to jump on the bandwagon of the Islamic peril”; Leela Jacinto at Foreign Policy with some broader context; and Charlie Hebdo cartoonist Luz’s concession that “sometimes it doesn’t work, other times it’s simply beautiful.”

While calls for press restrictions irked some, another controversial aspect of state media coverage was CCTV’s alleged misrepresentation of Wang Fanghui, a Chinese resident of Paris who had encountered the killers shortly before the attack. The state broadcaster claimed to have coaxed a cowardly Wang into giving his first interview, although he had already spoken publicly to French media. Wang appealed to his former classmate, Caixin’s Zhang Jin, for an explanation:

I’m not a hero and it was mere coincidence that I faced a killer’s gun barrel. I stood out and talked to the media after a narrow escape from death just so I could begin with my healing process psychologically.

But the reporter’s upside-down remark has left my attempt in ruins and hurt my reputation. To say the least, it was a stab to an open wound.

I simply don’t understand why a journalist would have called white black when faced with the facts. Besides, the sentences she added were trivial and had nothing to do with the point of the news.

Zhang Jin, buddy, you are also a media worker. Why did she make up the words she said? Do you have any idea? [Source]

On China’s social media, meanwhile, some felt that China had been unfairly denied the kind of sympathy and solidarity shown to France. From Tea Leaf Nation’s Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian and Rachel Lu:

[…] “In the Kunming knife attack, 29 people died,” one Weibo user wrote in a popular Jan. 12 comment in response to the Paris march, “but many Western countries didn’t acknowledge this as a terror attack. The Western double standard in defining terrorism is revolting.” Another user complained, “After Kunming, the West was unified in criticizing China’s human rights, not criticizing terrorism.” Another user wrote, “The West always thinks that it is infallible to use its own values to judge the entire world. Although I oppose violent terrorism, I am similarly irritated by Western hypocrisy.” One Weibo user invoked the French president’s Jan. 11 declaration. “After the Kunming attack, did Western media say, ‘Today, Kunming is the capital of the world’?”

[…] There was no great show of unity on Chinese streets after Kunming, perhaps because authorities would have been unlikely to approve mass gatherings that touch on the sensitive issue of domestic terrorism. Citizens in China may wish they had been entitled to such a moment of catharsis. “I don’t understand the comparisons with Kunming,” one Weibo user wrote. After that attack, “Tell me, did similarly large crowds stand up? If everyone remains silent, how are other people going to pay attention to us?” [Source]

There are possible explanations for Western responses aside from anti-Chinese feeling. Regarding the initial reluctance to label the Kunming attack as terrorism, The New York Times’ Edward Wong commented:

Some Chinese say Westerners are too skeptical about China terrorism reports. 2014 story by @thewanreport shows why. http://t.co/RcyvEe5ukD

— Edward Wong (@ewong) January 15, 2015

[… T]he sleepy village of Luokan is about as remote and unlikely a place for terrorism as can be found. Yet when police fatally shot a man recently in the middle of a busy market here, they declared him a terrorist as well and abruptly closed the case.

“But everyone knows this is a lie,” said one villager in a hushed midnight interview inside his home.

“There are no terrorists here,” said another beside him. “The only ones we’re afraid of are the police.” [Source]

Read more on the post-Kunming arming of Chinese police and earlier disagreement over the use of the word “terrorism” via CDT.

As for the absence of visible Chinese marchers to inspire solidarity abroad, the AFP’s Felicia Sonmez agreed:

My own 2 cents: BJ doesn't allow large gatherings and holds monopoly over info related to attacks. No unity rally bc govt doesn't want it.

— Felicia Sonmez (@feliciasonmez) January 13, 2015

That doesn't mean, of course, that govt doesn't want to continue promoting the 'West doesn't care about terror in China' line.

— Felicia Sonmez (@feliciasonmez) January 13, 2015

A similar contrast to that between Paris and Kunming emerged as coverage of the Charlie Hebdo incident eclipsed news of a series of Boko Haram attacks in north-eastern Nigeria. As many as 2,000 people have been killed in the town of Baga this month, while last Saturday a 10-year-old girl was used to carry a bomb into a crowded market. While expressing disappointment with the lack of international attention to these events, bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah suggested that the lack of visible demonstrations by Nigerians had been a factor. “Whatever the world does should be an amplification of what we ourselves are doing for our country,” he said according to The Financial Times. “You can’t cry more than the bereaved.” The originator of last year’s #BringBackOurGirls campaign Hadiza Bala-Usman similarly noted that “what is happening in France is so symbolic for us in terms of what we have not been able to do to come together in this region.”

The fact that #BringBackOurGirls did succeed in drawing Western attention to the region, together with the role of the #jesuischarlie hashtag as a beacon for solidarity with France, highlights another issue. Because Twitter is an international platform, both movements were able to hop borders and gain global momentum with relative ease. Beijing, though, has deliberately cultivated its own separate archipelago of homegrown social media platforms, penning in any hypothetical #woshiKunming (#IamKunming).

Global Voices cofounder Ethan Zuckerman noted the proposed explanation that “Baga is hard to get to, while Paris is a global media city. Easier access equals more coverage.” What coverage there has been from Baga has been based largely on patchy eyewitness accounts and satellite imagery as continued violence keeps observers at bay. Foreign and domestic media in China face less dramatic but still substantial obstacles. Domestic coverage of Kunming declined sharply and almost immediately as Chinese authorities managed news and social media to reduce strain on ethnic relations and avoid further unrest.

Even if Chinese authorities had been trusted, reporting unfettered, and social media globally integrated, Kunming might have failed to attract the level of support that arose for Charlie Hebdo. To explain but not excuse the lack of attention paid to Baga, Zuckerman turned to Johan Galtung and Mari Ruge’s 1965 paper ‘The Structure of Foreign News,’ in which they identify twelve factors in a story’s perceived newsworthiness. He highlights four of these principals which might also shed light on Western responses to Kunming:

[…] Meaningfulness: The central metaphor of Galtung and Ruge’s paper is a shortwave radio – of all the signals we tune into on the radio dial, we are most likely to tune into those that have meaning for us, say a human voice speaking in a language we understand. Meaningfulness includes cultural proximity: we are more likely to pay attention to events that affect people who live lives similar to our own. […]

Consonance: While news is usually a surprise – a natural disaster, an unanticipated death – Galtung and Ruge argue that we like our surprises to be consonant with narratives we already know and understand. […]

Unambiguity: We like stories that are easy to understand and interpret – nuanced and complex events are harder to cover than unambiguous ones. […]

Stories about people: Stories need heroes and villains. Coverage of the Paris attacks has focused on Charlie Hebdo editor Stephane Charbonnier and his willingness to “die standing than live on my knees”, and the long histories of the radicalization of Cherif and Said Kouachi. […] [For those unwilling to embrace the cartoonists as heroes, Ahmed Merabet and Lassana Bathily provide alternatives.]

If Galtung and Ruge’s principles hold, we shouldn’t expect attention to the Baga massacre to increase in the next few days. It’s too distant, physically and culturally, too complex and devoid of the personal narratives journalists use to draw audiences to complex stories. But it’s critically important that we understand what happened in Baga, not just to understand the challenges Nigeria faces from Boko Haram, but to understand who religious extremism affects. [Source]

The Paris march provided another illustration of China’s global position, according to Tim Fernholz at Quartz:

The political furor of the day in the US was the Obama administration’s decision not to send anyone more visible than the American ambassador to last weekend’s dramatic march in Paris, where numerous world leaders joined millions in solidarity with the terrorist attacks there. [See Politico for background.]

But nobody’s asking the same question of the supremo in the other global super-power, Chinese president Xi Jinping, which has had faced its own terror problems recently. Chinese leaders aren’t expected to pay attention to anything but their own interests; indeed, their official news agency’s response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks was to make the case for more press limits.

If the measure of a country’s soft power is what people expect of their leaders, even in truancy Obama is demonstrating the advantage US leaders have over their undemocratic rivals [….] [Source]