While the ongoing lockdown of Xi’an has thrust millions of people into health and food insecurity, online public outrage must contend with state media’s heart-warming stories of “noodles helping noodles.” Even Jia Pingwa, the lauded author whose 1993 novel “Ruined City” was banned for 16 years, has put out an appeal to “extinguish our fear” and “vanquish this pandemic.” But Jia’s boosterism should come as no surprise: he is Chair of the Shaanxi Writers Association and a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. In a biting WeChat commentary, posted on January 5 and translated in full below, WeChat author @老萧杂说 argues that clear-eyed critique, not effusive cheerleading, is what Xi’an really needs from its most famous man of letters:

I haven’t written so much as a word throughout the Xi’an lockdown, now 14 days and counting.

When Wuhan locked down, I penned over ten essays. I’m from Hubei Province, so naturally I paid that region a little more attention.

But of all of China’s provincial capitals, I’ve been to Xi’an the most often, and I have the most friends there.

My lack of writing about Xi’an does not mean I’m indifferent to the situation there. A number of my friends are stuck there, either at home or in hotels (if they happened to be traveling there.) I can’t help but ask them if they’re all right, if they have food, or if they’ve been “dug up like radishes” and taken to quarantine outside the city limits.

I’m well aware of all the stories from the Xi’an lockdown that have leaked to the media. Each one is worthy of comment.

But I haven’t written anything yet, because everything happening in Xi’an has already happened—in Wuhan. Some of the stories are so familiar, they could have been based on the same plot. Even if the situation in Xi’an ends up worse than Wuhan, what more can I say?

It’s like Lu X— said: “I could not bear to hear the news. What else is there I can say?” Sure, the circumstances are different, but the feeling, the mood, is the same.

How many lockdowns have there been? Wuhan, Tonghua, Shijiazhuang, Yangzhou, Ruili—couldn’t Xi’an have learned from their mistakes, taken them to heart, borrowed a page from their book, and come up with some sort of contingency plan?

Even at the risk of having this post deleted and my account banned, it needs to be said: based on my long understanding of the level of incompetence, vapidity, and cowardice of certain city and provincial officials, everything that is happening to Xi’an now was foreshadowed and foreordained.

To reiterate: this is undoubtedly the case. Absolutely no progress has been made combating the corruption of local officials since the Qinling Villas debacle.

This time around, their rigidity, arrogance, indifference, flip-flopping, and disorganization have brought suffering on 12 million ordinary citizens. So too have they hurt all those individuals working tirelessly on the front lines of this pandemic.

If Jia Pingwa hadn’t spoken up, I would have remained silent. The words of a peon like me carry little weight, after all. What use would it be to speak out? Plus, if you’re not careful, they’ll say you’re just trying to capitalize on the hype.

The thing that keeps nagging at me is that of all the intellectuals in this cultural capital, not one has bothered to write an account of events. And, frankly, complete silence would be better than this sort of third-grade-level drivel:

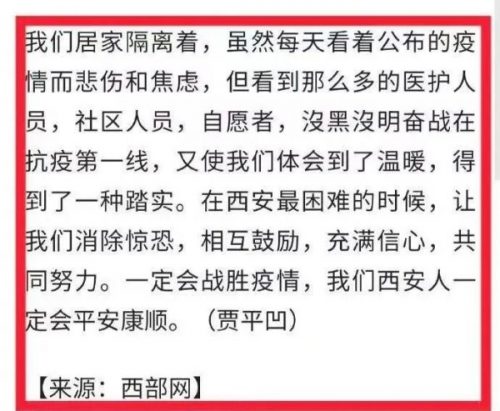

A screenshot of Jia Pingwa’s short message of support to the people of Xi’an

We are quarantined, isolated in our homes. Though we are saddened and troubled by the daily news of the pandemic, we also see all the medical and community personnel and volunteers, fighting tirelessly day and night on the front lines. From them, we derive a sense of comfort and peace of mind. Here in Xi’an, in our time of greatest difficulty, let us extinguish our fear and encourage one another, our hearts filled with confidence as we work toward our common goal. We will vanquish this pandemic, and the people of Xi’an will be safe and sound. (Jia Pingwa) [Chinese]

It’s impossible to know the circumstances under which Chairman Jia made this “moving” statement. With the entire city preoccupied with achieving “zero-COVID,” perhaps officials in Xi’an have been too busy to mobilize a unified front of cultural figures to support the city’s pandemic response.

Most likely, Jia’s comments were a “personal action.”

The group of writers known as the “Shaanxi Army” once commanded great respect. Having lived through so many missteps and vicissitudes in their own lives and in the life of the nation, they knew firsthand the suffering of ordinary people, and so were able to create works of literature that examined the cultural history of a nation and celebrated the lives, deaths, joys, and sorrows of the proud inhabitants of that yellow soil.

They did not shrink from suffering—in fact, they made it their close companion. In exchange, they were able to tap into the lives and consciousness of ordinary people, as well as their own sense of compassion. This is both the great misfortune and the great fortune of Shaanxi literature, a sort of God-given creative blessing.

It is precisely this aesthetic of confronting suffering that cultivates the compassion found in Shaanxi literature. It has spurred Shaanxi authors to express their deep concern and sympathy for the lowly and disadvantaged, so as to awaken our collective conscience and sense of humanity. From this, the unique, bitter spirit of Shaanxi literature was born—facing hardship, bearing it, and ultimately transcending it.

Each time a city locks down, the lockdown itself borders on tragedy. The current lockdown in Xi’an is being enforced at all costs and on all levels: provincial, municipal, and individual. If someone can feel sympathy for Xi’an from a thousand miles away, then surely Chairman Jia can be moved.

But given the life-and-death immensity of the situation, the great tragedy unfolding around you, is it enough to simply say you “feel moved”?

In the face of human suffering, salvation far outweighs eulogy, and criticism carries more practical value than praise. This is what literature is for: to tell the stories of ordinary people, of their suffering, of their misery.

Jia Pingwa is one of Shaanxi’s finest authors, and he, more than anyone, embodies the bitter spirit of Shaanxi literature. When he respects reality, respects life, and cherishes compassion, his words brim with spiritual power, as we see in “The Castle,” “Turbulence,” and “Meixuedi.”

But after “Ruined City,” although he remained highly productive, his writing lacked the requisite underpinning of lived experience. As a result, “White Nights,” “Earth Gate,” “Old Gao Village,” “Wolves of Yesterday,” “Health Report,” and other later works exhibit a certain inconsistency, an elusive quality.

Today, Shaanxi literature is in a state of creative decline, stripped of its former glory. The literary movement in which the “Shaanxi Army conquered Eastern China” is but a footnote, mentioned only in university classrooms.

The fall of Shaanxi literature is due in large part to the fact that Shaanxi authors have ignored the people’s hardships. They leave too much of lived experience unexcavated.

In terms of mere social status and professional rank, Jia Pingwa is unquestionably the leading light of the Shaanxi literary world. In this time of global pandemic, Jia should be hoisting high the spirit and ideals of literature, and elevating the aesthetic character and social value of Shaanxi literature in pursuit of aesthetic clarity.

In this sense, the people of Xi’an can wallow in sentimentality about this pandemic or any other disaster, but Jia Pingwa should show some restraint.

He is moved too much. Jia Pingwa is a true writer no more. He’s a bona fide Chairman Jia now.

Sentimentality is cheap. Showing a modicum of restraint, whether or not you live off your words like Jia, is less likely to come off as pablum. [Chinese]

Translation for CDT by Little Bluegill.