Popular online writer Shen Maohua, who writes under the pen name Wei Zhou, is known for his trenchant and often humorous essays, lively social media comments sections, and occasional brushes with platform censors.

In this classic Wei Zhou essay from March 2022, he tries to help his readers understand how and why some of their comments disappear from his WeChat public account. In the process, we gain insight into the methods of platform-based censorship, the relationship between an online writer and his readers, and the careful balancing act required to keep a popular social media account up and running in China today.

“Why did my comment disappear?” I’m often asked this question, and though I’ve explained it countless times, it seems that a lot of my readers still don’t understand what’s going on. Since I’m tired of explaining it separately to each person who asks, I may as well write a quick post to demystify things.

A reader once angrily demanded to know: “Why would you take my comment down after making it public? What kind of fickle game is this?” Someone more diplomatic might have said: “Censoring readers’ opinions and commentary doesn’t seem your style.”

Although this is my own turf, I don’t get to call the shots. Some comments simply disappear after I pin them to the top of the comments section. Think about it: when I pin a comment, it means I strongly agree with its viewpoint, so there’s no reason I’d go back and delete it. Then there are the comments that disappear after I respond to them. There’s simply no logic behind this: if I respond to a comment, of course it means I want you all to read it, so why would I go to the trouble of deleting it?

I think it’s no surprise to anyone that when it comes to online public opinion, platform admins participate in each and every discussion. To give a rough estimate, somewhere between one-half to one-third of the reader comments that I choose to make public simply disappear. Of course, the readers can’t see what’s going on, but I can, behind the scenes.

Some people are aware that WeChat is subject to a certain amount of control, but they don’t understand what policies govern that control. As one reader said: “I thought that if they wanted to control things, it’d be like on Douban where they’d directly notify you that your post had been taken down. When I saw that a comment was no longer visible, I just assumed it was the author who changed their mind and deleted it after making it public. Recently, it seems that no matter what I post, it gets deleted immediately. It’s really frustrating ….”

Even I don’t receive those sorts of notifications (one day last month, I was notified every time a comment was deleted, but it turned out to be too overwhelming.) Since the comments section in WeChat public accounts is limited to 100 comments, here’s how it typically works: I’ll select 100 comments to make public, and after a while, I’ll discover that about 40 of those have been censored (this requires combing through all 100 to make sure.) By this point, even more comments have flooded in, so in order to make room for new comments, I have to unselect the public comments that were censored. I can’t even use the desktop-client dashboard to take down comments deemed to be in violation of the rules; I have to scroll through them manually on my phone. Even then, it’s possible that some of these new comments might get censored, which starts the whole cycle yet again ….

Because this process is so tedious, sometimes when the comments section gets locked down, I feel a strange sense of relief that I no longer have to rack my brains trying to select which comments to make public.

I don’t know why the comments section is limited to 100 slots. Whenever I get more than 100 comments on one of my essays, it adds to my workload because I have to put in a lot of effort deciding which ones to make public. To ensure that everyone has an equal opportunity to speak, I often have to remind people not to post a bunch of comments under a single essay, because that takes up multiple slots. If you have a lot to say, you might as well just reply to your first comment. That way, you’ll only take up a single slot.

It was only later that I realized some people have older phones that don’t allow them to reply to their own comments. Others post multiple comments to hedge their bets, figuring that if one comment is deleted, the others will still stand. There was one reader whose comment received a ton of likes, but then he replied to his own comment, and the whole thread disappeared. I said, “Oh no, you were on a roll, why’d you have to go and add that extra comment?” He replied, “I was all fired up … nah, actually I just didn’t have anything better to do.”

Although this is a bit speculative, over time, I’ve more or less developed a sense of which comments will get censored. Once, I came across a particularly forthright comment and couldn’t resist offering the commenter my two cents: “If I make your comment public, it’s going to disappear right away.” But he was adamant: “What I write is my business. Whether or not you want to make it public is your business.” Of course, what happened after I made his comment public was entirely predictable.

Because I imagine most readers don’t want their comments to stay under wraps forever, as long as there are slots available, I’ll typically try to make comments public as soon as they come in. It sometimes happens that I move too fast, and only after selecting a comment do I discover the words “Don’t post this publicly” written at the end, so then I have to scramble to deselect it. Also, because I’m so quick, some readers get the mistaken impression that the comment selection process is automated, when in fact, all public comments are manually selected by me!

I’m the kind of person who feels that there shouldn’t be any limit to the number of comments. Apart from a very small number of abusive attacks, I prefer to make all comments public and let readers judge for themselves, with minimal intervention on my part. And because I’m pretty laissez-faire, and take a neutral stance toward my essays, the comments section naturally tends to attract a diversity of opinions. Sometimes readers tell me that they come not to read my essays, but to read the comments.

February 20, 2022 7:49 PM

Dear Mr. Wei Zhou,

I’ve been a hardcore fan of yours all along. I really enjoy your essays, and admire your moral character even more. Most of my comments are reckless and rambling, and aimed at spreading rebellious energy. As long as you see them, that’s all I care about, and if you think they’re too sensitive then don’t bother making them public. I couldn’t care less if my account gets blocked, but if yours ever did because of one of my comments, I’d feel awful.

March 6, 2022, 3:19 PM

Recently, WeChat’s admins have removed a lot of comments that you made public, which on the whole, must have been a big headache for you. I want to apologize to you for all that, but next time, I still won’t be able to resist posting comments, even those that aren’t very “harmonious.” I can’t help it: I’m game despite my lack of game, just a loud-mouth without the skillz to prevent my comments from getting deleted, haha … I’m seriously hooked, and reading your essays is my fix. Thanks!

I’m also thankful for how considerate my readers are, so much so that some of them even tell me not to make their comments public, for fear of causing me trouble. Here’s the reason why I have to accept responsibility: as the administrator of this account, I am responsible for keeping the comments section “clean,” as it were, so if any “issues” arise, it means I’ve been careless in my duties. The harshest penalty was in February of last year when the comments function was disabled for a full five days.

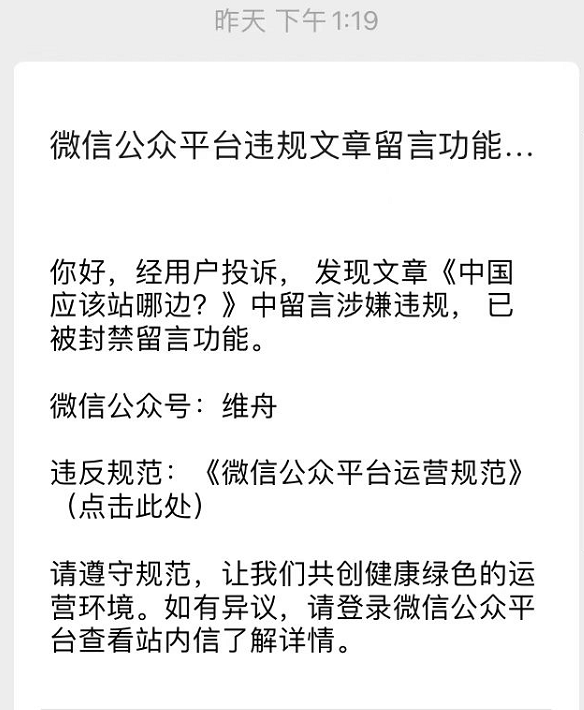

Take yesterday’s essay, “Which Side Should China Be On?”, which provoked fierce debate and was flooded with 112 comments within the first hour of being published. The controversy was most likely due to the essay’s title, as it didn’t seem like many people had read the essay or grasped its logic. The upshot of all the heated debate was that the comments section quickly disappeared:

Yesterday, 1:19 PM

Violation of WeChat’s Public Platform Regulations on Comments Control

Hello. Following a user complaint, it has been found that certain comments under your essay “Which Side Should China Be On?” may be in violation of platform regulations, and as such, the comments function has been disabled.

WeChat Public Account Holder: Wei Zhou

Regulations Violated: “WeChat Public Platform Operating Standards” (Click here)

Please abide by all regulations, so that together we can build a green and healthy operating environment. If you dispute this decision, please log into the WeChat Public Platform and check your inbox for further details.

Among those readers who surmised that the comments section was blocked, one individual was so curious as to what the fuss was all about that he/she asked if I could forward some screenshots of the offending comments. Among those who couldn’t fathom what had happened, a few were itching to get in one last word, and chased me down, angrily demanding to know, “Why are you so scared to open the comments section?” There was even one reader, a new subscriber, who “liked” my essay and then left me the following message:

March 19, 2022 9:15 PM

Can’t you enable a discussion feature? As your essays lean towards theoretical analysis, it’d be somewhat of a loss if there weren’t a clash of opinions!

This has happened so many times that I guess it needs to be explained every once in a while, but I’m tired of having to explain myself, and it seems that there are still a lot of people who don’t get it. So let me explain yet again: I would never, ever close the comments section, so if you see that the comments have disappeared, you don’t even need to ask: it just means the admins have been at it again.

In fact, for all WeChat public accounts registered after February 2018, the comments function has been disabled, and this remains the case four years later. In order to allow readers of Wei Zhou’s Ark [@维舟的方舟], my secondary account, to continue chatting, I was forced to add a mini-program message board.

What ended up happening was totally unforeseen: the WeChat admins couldn’t delete comments because the mini-program wasn’t under Tencent’s control, but it also gave free reign to some of the trolls that I had previously banned. At one point, I even started to feel that there were some benefits to keeping the comments section within Tencent’s purview.

I believe that I have been consistently tolerant and respectful of everyone’s right to speak. However, after experiencing several unhappy ordeals in which my account was blocked and my essays deleted, in addition to banning abusive or threatening speech, I have absolutely no qualms about axing any comments that could prove risky.

Every time my content is deleted or my account blocked, many readers invariably ask what happened. I always give them the same brief explanation, yet not everyone seems able to understand. The last time I wrote such an essay (“Explainer: The Essay That Disappeared Yesterday”), one reader sent me this mocking comment: “Do you actually think getting your essay deleted is a badge of honor?”

After I made his comment public, the admins came back and deleted it, which added fuel to the fire and worsened the misunderstanding, because he assumed that I was the one who deleted it. In trying to explain the platform’s policies, I wrote to him: “As for your assumption that it’s some kind of badge of honor, I can definitively tell you it’s not. Given the choice, who would actually want their essays to be deleted? Your motivational theory is so bad it’s funny.”

But he refused to back down:

“Then explain why whenever an essay is deleted or your account blocked, you always make a point of posting one or two essays crying about what happened. I’ve always enjoyed your essays, but whenever I see these “badge-of-honor-type” eulogies, I’m revolted. I’ve always wanted to ask that, but have been holding back until now. It’s like what I said in a previous comment: everyone knows what the rules are, and nothing and nobody is going to change that in the long run, let alone in the short run. You clearly know this, so why are you scoffing at my motives?”

His point was this: The rules are there by default and won’t be changing any time soon, so what’s the point of bringing them up? Better to just keep quiet and carry on without complaint. Grousing about it makes it sound like you’re treating your deleted essays and account blocks as badges of honor. By the way, when I ridiculed him for his “motivational theory,” I was referring to his speculation about my motives.

I imagine that no small minority of people share his way of thinking—he just happened to be more forthright about it. Once I’ve finished writing this piece, it’s probably unavoidable that some people will be made uncomfortable by it. I’m sorry about that, and I don’t want things to be this way. If only it were possible, I would very much like to not waste time and energy repeatedly explaining things like this. [Chinese]

Translation by Hamish.