While China’s leadership has long seen the media as the CCP’s “throat and tongue,” official efforts to control the news narrative have substantially increased under the rule of General Secretary Xi Jinping. As Xi’s administration has overseen a widespread crackdown on civil society and legal advocacy to deter criticism and reinforce ideological orthodoxy, it has also encouraged Chinese reporters to adhere to a “Marxist view of journalism,” and has set new records for the number of journalists behind bars. Media organizations have faced the threat of closure for not following censorship directives, foreign correspondents have been expelled from the country while foreign-funded companies face new hurdles to online publishing, reporters detained after filing critical reports, and state media editors stripped of employment and Party membership after questioning state policy. The increasingly tight media landscape has reportedly scared some young journalists away from the industry entirely, and even elicited an unexpected call from Hu Xijin, editor of the nationalistic state media tabloid the Global Times, for “greater tolerance” of criticism.

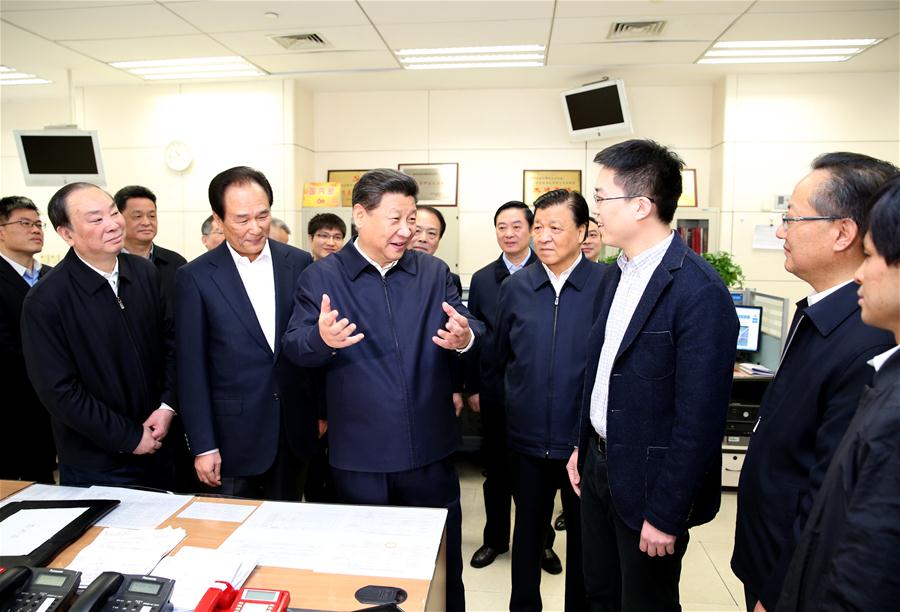

On Friday, Xi Jinping visited the headquarters of the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, and CCTV—China’s three leading state media providers. Xinhua reports on Xi’s comments from a symposium following the visits, which hint that his administration has no intent to loosen control over the media:

All news media run by the Party must work to speak for the Party’s will and its propositions and protect the Party’s authority and unity, Xi said.

They should enhance their awareness to align their ideology, political thinking and deeds to those of the CPC Central Committee and help fashion the Party’s theories and policies into conscious action by the general public while providing spiritual enrichment to the people, he said.

Marxist journalistic education must be promoted among journalists, Xi added, to make them “disseminators of the Party’s policies and propositions, recorders of the time, promoters of social advancement and watchers of equality and justice.”

According to Xi, the mission of the Party’s media work is to provide guidance for the public, serve the country’s overall interests, unite the general public, instill confidence and pool strength, tell right from wrong and connect China to the world.

To do so, Xi continued, they should also stick to guiding public opinion on the correct path in every aspect and stage of their work. [Source]

At The Wall Street Journal, Chun Han Wong delivers details from Xi’s stops at the three state media outlets, and quotes China Media Project’s David Bandurski on how anxiety among the central leadership may be precipitating the further prioritization of media control:

“It’s a very sensitive time economically, and even without the downturn, China is facing a whole array of really complicated social issues,” said David Bandurski, a researcher at the Hong Kong-based China Media Project. “There is a nervousness [within the Chinese leadership], and this makes media and information control that much more of a priority.”

[…] “Xi Jinping has been much more active from the get-go in terms of asserting control over information,” said Mr. Bandurski, the researcher. “He has cultivated a more robust presence in official media than previous leaders.”

[…] CCTV, for its part, invited the president to try his hand at newsreading. Flanked by top party propagandist Liu Yunshan, officials and news anchors, Mr. Xi took the hotseat on the studio set used by the broadcaster’s flagship evening news bulletin, Xinwen Lianbo, a CCTV video showed.

It wasn’t clear what Mr. Xi said to the cameras. The video was paired with a lilting cadence but no audio from the scene. [Source]

Exclusive: President #XiJinping visits the studio of CCTV Evening News Bulletinhttps://t.co/cpe3xdp9PN

— CGTN (@CGTNOfficial) February 19, 2016

Also see a recent report from The Economist on Xinwen Lianbo and its efforts to gather public confidence and affinity for Xi. At Medium, Bandurski notes that Xi’s state media tour will likely “shed further light on media policy at the very top in China” in days to come. The researcher continues to offer a translation of an obsequious poem to Xi from Xinhua deputy editor Pu Liye that is drawing ridicule on Chinese social media platforms.

During Xi’s stop at CCTV, a large studio teleprompter, possibly intended to remain off camera, declared: “CCTV is Party Family; Absolutely Loyal; Please Inspect Us.” Global Voices Oiwan Lam notes that CCTV also aired a vox populi segment, reinterpreting the Confucian concept of “filial piety” (xiào 孝) as something that should first be shown to the state; netizens replied with mockery.

Nervousness within Party leadership, mentioned above by Bandurski (via the Wall Street Journal), may also help explain China’s ideological climate beyond the media landscape. At Project Syndicate, professor Minxin Pei described the current atmosphere as characteristic of a “return of [the] fear-based governance” of the Mao era, citing ongoing campaigns against Party corruption, critical foreign journalists, liberal ideas in the academy, human rights lawyers and civil society activism, and Hong Kong publishers known for printing salacious tales of mainland leaders. In a ChinaFile conversation around the “rule by fear” thesis, CDT founder Xiao Qiang explains how fear exists on both sides of the political relationship, a fact directly highlighted by media censorship:

Under Xi, the crackdown on civil society in general, and on the Internet in particular, is both the Chinese leaders’ acting out of fear, and creating a sphere of fear in Chinese society. This can be described as “rule out of fear” as well as “rule by fear.”

(“Rule out of fear” (of a coup) can also apply to Xi’s “anti-corruption” campaign against high-level political opponents such as Zhou Yongkang, Xu Caihou and Ling Jihua.)

Three years into Xi’s rule, just how effective his “rule by fear” approach is is still an open question. In late 2015 and early 2016, the signs of resistance to this “rule by fear” are everywhere, both within the Party and in the general population. […]

[…] For those who are familiar with Chinese Internet political expressions, those “banned” terms are already popular memes; most of them cast a very critical light on the regime’s ideological foundation and especially on the political image of Xi Jinping. One of those words is a new nickname of Xi Jinping—“Da Sabi (大撒币).” It can be translated as “big spender,” a play on the literal translation of the words sā bì 撒币 “throw money” and “stupid cunt” (shǎ bī 傻逼). The nickname takes aim at the economic aid Xi has promised to foreign countries; the moniker is so widely used on Chinese social media that the censors’ repressive measures only draw more attention to it, and to the criticism embedded within it.

Such resistance should caution observers from overemphasizing the lasting impact of “rule by fear,” and make us attentive to a potential, even partial, failure of such “rule by fear.” Such a failure can only generate greater fear among top Chinese leaders, especially Xi himself, and lead to more desperate and risky actions in order to maintain his personal power legitimacy, especially while the Chinese economy starts to slow. [Source]

The AP’s coverage of Xi’s state media tour quotes the University of Hong Kong’s Willy Lam, who also sees looming insecurity as a major motivator for the president’s ongoing drive to promote ideological orthodoxy to the Party and the masses:

Willy Lam, an expert on elite Chinese politics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said Xi is raising standards for state media by requiring they obey the will of the Communist party’s core leadership, which is increasingly defined by Xi himself in another sign of how he has accrued more personal authority than either of his last two predecessors.

“This is a very heavy-handed ideological campaign to drive home the point of total loyalty to the party core,” Lam said. “On one hand, Xi’s influence and power are now unchallenged, but on the other hand, there is a palpable degree of insecurity.”

Lam said Xi faces lurking challenges not only from within different party factions but also from among a disaffected public, who are unhappy with the slowing economy and a recent stock market meltdown. [Source]

Like Minxin Pei, Lam too sees a parallel between Xi’s governance and Mao’s, and recently wrote an essay for China Brief on fears that Xi could beckon in a new Cultural Revolution.

In his symposium on Friday, Xi also took the chance to call on state-run outlets to better tell China’s story to the world by boosting their international influence. Reuters’ Ben Blanchard and Michael Martina report, highlighting controversy in recent efforts to boost China’s external propaganda reach:

Chinese state media must tell China’s story to the world better and become internationally influential, President Xi Jinping said on Friday, during a visit to three of the country’s main media outlets.

Chinese news outlets spanning television, radio and the Internet have been expanding across the globe with state encouragement, aiming, Chinese leaders have said, to combat the negative images of China they feel are spread by world media.

State news agency Xinhua has opened dozens of news bureaus around the world; China Central Television (CCTV) has launched a 24-hour English-language channel in the United States, and the official China Daily newspaper publishes several regional editions across the globe.

[…] China’s efforts to expand its global media footprint have been controversial.

Reuters has found that state-owned China Radio International (CRI) has little-known ownership stakes in a global network

of private radio stations from Houston to Finland to Bangkok in partnerships with overseas Chinese.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice have said they are investigating a California firm whose U.S. radio broadcasts are backed by CRI. [Source]

While at CCTV headquarters prior to the symposium, Xi reached out to the staff at CCTV America, which began operating in Washington just prior to Xi’s ascendancy to the Party helm. The president praised their efforts, and delivered a personal appeal to continue “telling true stories of China, publicizing Chinese culture, and building a friendly bridge with locals”:

As Xi calls for the expansion of state media influence abroad, central authorities recently unveiled new guidelines that could stifle the inflow of foreign media. Quartz’ Heather Timmons and Zheping Huang report on new rules from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television that could effectively block foreign-invested companies from publishing any online media in China:

The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s new rules (link in Chinese) could, if they were enforced as written, essentially shut down China as a market for foreign news outlets, publishers, gaming companies, information providers, and entertainment companies starting on March 10. Issued in conjunction with the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SARFT), they set strict new guidelines for what can be published online, and how that publisher should conduct business in China.

“Sino-foreign joint ventures, Sino-foreign cooperative ventures, and foreign business units shall not engage in online publishing services,” the rules state. Any publisher of online content, including “texts, pictures, maps, games, animations, audios, and videos,” will also be required to store their “necessary technical equipment, related servers, and storage devices” in China, the directive says.

Foreign media companies including Thomson Reuters, Dow Jones, Bloomberg, the Financial Times, and the New York Times have invested millions of dollars—maybe even hundreds of millions collectively—in building up China-based news organizations in recent years, and publishing news reports in Chinese, for a Chinese audience. Many of these media outlets are currently blocked in China, so top executives have also been involved in months of behind-the-scenes negotiations to try to get the blocks lifted.

[…T]he new rules would allow only 100% Chinese companies to produce any content that goes online, and then only after approval from Chinese authorities and the acquisition of an online publishing license. […] [Source]