In 2016, citizen journalist Lu Yuyu and his then-girlfriend Li Tingyu were formally arrested after having been detained for over a month for chronicling “mass incidents” across China on their “Not News” (非新聞) blog and @wickedonnaa Twitter account. After the two were awarded a Press Freedom Prize from Reporters Without Borders in 2016, Li was reportedly freed, and Lu was sentenced to four years in prison for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a catch-all charge frequently used to prosecute activists.

After serving his four years, Lu Yuyu was released from prison in June of this year. The following month he began sharing a multipart account of his treatment in detention on Twitter, ending with an entry about his sentencing and transfer to Dali Prison. In August, he was issued a warning by local police for circumventing internet controls, and was told not to speak to the media.

Earlier this month on Matters, Lu published another large chunk of his prison diary, “Incorrect Memory,” which CDT has translated in full.

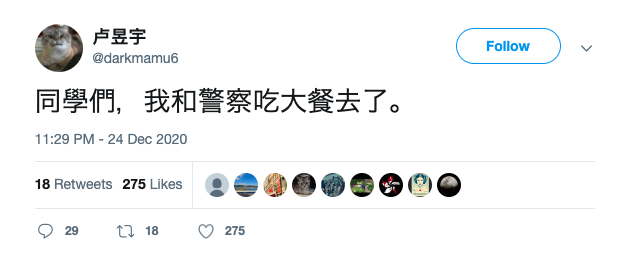

This Christmas Eve, Lu tweeted that he was “off to have a banquet with the police.”

“Classmates, I’m off to a banquet with the police.”

Incorrect Memory (II)

“Stop! Don’t come any closer! I can write you up for assaulting an officer!”

It was a middle-aged prison guard yelling, his triangular eyes radiating a frosty stare. A younger, shorter guard stood next to him. The detention center instructor who was guarding me went up to speak to the older guard, smiling sheepishly. Then they started to go through my stuff. All I had was a few books.

“Nothing is allowed,” the older guard said in an authoritative tone.

I looked around. The officers who took me here looked helpless.

“Alright. I won’t take them.” I didn’t really have a choice.

After I walked past the two big gates, the officers took off my handcuffs and shackles and left with my books. The older guard threw me a set of striped uniforms, coldly ordering me to change. I hesitated before complying, trying to keep my temper in control.

“Excuse me Sir, the prisoner asks to cross.” As per their requirement, I requested permission from the armed guards who were standing up on the watchtower. Up to the day I finished my sentence, I never understood why we had to do this. But that didn’t matter. Most people would have to do this twice, when entering and exiting. Some only had to do it once, because they are never getting out.

After permission was granted, I crossed over the cordon.

Standing to the right of the gate were three U-shaped buildings with white-tiled walls. Red banners hanging on them read: “Know Your Crime, Acknowledge Your Guilt, Show Repentance…” They looked as ugly as the imagination-killing buildings at my high school with “Good Good Study, Day Day Up” hanging on them. In front of the buildings was a sports field with a few shabby basketball hoops. To the left of the gate, there were some banyan trees, a carefully manicured lawn, and a factory building that had sunk into the ground, its roof about at the level of the road with two raised porches protruding. There was no one else around except the two guards and myself, it felt like I had just stepped into a zombie apocalypse.

Carrying my clothes, I walked on. The two guards following me were joking about how the officer who just left was too obsessed with climbing the government ladder (it seemed like they knew each other). We took a left turn, downhill past two U-shaped factory buildings, a smaller sports field and some cherry blossom trees before reaching the prison cells, another U-shaped construction. I had to do a physical checkup first at the clinic on the first floor. The guards left after handing me to a hot-tempered inmate with upward eyebrows. It turned out that the entire physical checkup was performed by some hot-tempered inmates, including drawing blood and taking X-rays. Luckily, my veins weren’t punctured.

It was almost noon when we finished. I was then taken to the top floor, Floor 6. Like an office building, the cell building had a corridor in the middle and cells on both sides. In a room labeled “Gai Ji Wei” (Commission of Proactive Reformers), I filled out forms, was given a haircut, and was strip-searched again. The middle-aged guard came back, looked at the Statue of Liberty tattoo on my leg and said, “A running dog for American imperialism!” Again, I had to suppress my emotions. Across from the Gai Ji Wei was the dining room where inmates were having lunch. A relatively nice inmate handed me a bowl of rice and a bowl of vegetables, and led me to the front of the dining room. One badge on his chest had his info: Yang Xiaoze, Embezzlement, 10 years. Another badge had the black characters for “On-duty Staff” on a red background. Just as I was digging in, the middle-aged guard called an inmate over. The poor guy walked over, trembling, and got slapped in the face.

“You bastard, you better believe I can kill you if I want!” The guard yelled.

“… I’m sorry… I’m sorry…” The inmate kept his head down and murmured.

“Get lost!” The guard marched off.

In my former jail, some inmates would even dare to joke with the guards. It was obviously different here. Fear was carved into everyone’s face.

After lunch, Yang Xiaoze took me to the cell and handed me toiletries and bedsheets. I then learned that this place was called Cell Zone Five (New Inmates Division). The middle-aged guard was the division chief, family name Qian.

Yang Xiaoze and I were cellmates, the two of us a “mutual supervision group.”

This country has had a long history of “guilt by association,” And now, “guilt by association” has become a major control mechanism in prisons. The prison would divide inmates into groups of three or four to form “mutual supervision groups.” (The superintendents would do the actual work before having the guards confirm it.) Inmates from the same group are required to stay together at all times. If they failed to do that, or if one of them got into trouble, everyone would be punished. If the matter was serious, the whole cell zone, subdivision or even the entire division would be implicated. Many people worry more about being ostracized after breaking rules than about being punished by the guards.

Our cell was about 30 square meters large. Right above the door was a surveillance camera. On each side, there were three iron-framed bunk beds. At full capacity, a cell can hold 12 people. The team leader slept on Bed One. At the far end of the room was a window, sink, and two squatting toilets.

The guards’ office was around the corner. Unlike the cell, their office had windows facing the corridor. If inmates want to speak to them, they have to announce themselves at the window, through which the conversation would usually be conducted. If the matter would take longer, they’d move it to the “Gai Ji Wei”—inmates were not allowed to enter the guards’ office.

There were too many new inmates, so our cell was over capacity, and newcomers would have to sleep on the floor until someone got reassigned. In the evening, Yang Xiaoze asked to see my court papers. The he said:

“You got sent to prison for this? Don’t worry. Your sentence is short and it can be commuted once. You can deal with them after you get out.

“Their policies change all the time. It’s harder and harder to get your sentence commuted. I had trouble every time I tried to do it. Otherwise I would have been out last year,” he went on. He was a teacher in a small town and was sentenced to 10 years for embezzling project funds. He had been inside for six years.

At night, people kept getting up for the toilet. I couldn’t get any sleep on the floor. And there were some cats meowing in the yard outside.

After Jane and I moved to Gantong, every time we came home Xiao Chou would be waiting for us on the concrete rail 50 meters from our apartment. He would meow, rub himself against our legs and follow us home. Xiao Chou liked to go out and play, and when he came home, he’d meow at the door for us to let him in. Thinking that we may not be able to let him in every time, I built him a shabby stairway so he could climb up to the second floor. It took him one day to figure it out. Since then, he was free to roam around. And he would bring us gifts of dead mice. Xiao Chou liked catnip. I wanted to plant some catnip at our apartment so he could bring friends over. I ordered some seeds and a rectangular planter box from online. The day it arrived, June 15, was the day we were taken away.

The “superintendents” here were well-connected inmates. Mostly officials or civil servants on the outside, they weren’t required to do hard labor, and would just help the guards with paperwork and management. Their status was in between a guard and a regular inmate. I often saw them scolding new inmates. A few years back, the superintendents were allowed to beat up newbies. They had stopped doing that because, from what I heard, some superintendents got punished after they damaged someone’s internal organs. They didn’t scold me, though, and often chatted me up. I was no doubt a key person for eyes to be kept on.

It turned out that the inmate I met on my first day, the one with upturned eyebrows, used to be a county mayor. He was also one of the superintendents here. He asked for my court papers. He said: “I know about this incident, it happened in my town. A villager was put in prison for that. He’s serving in Zone 8.”

He was the mayor of Binchuan County. No inmates would call him by his real name. Everyone called him County Mayor. Just like Yang Xiaoze, he was also here for embezzlement. County Mayor didn’t have much to do except to take new inmates to the clinic. He was possibly the most under-worked inmate.

Not required to do labor in the New Inmates Division, we could sleep until 7 in the morning, get settled and have breakfast: cold rice and vegetable soup, or instant noodles. New inmates couldn’t buy things and could only have the soup or have acquaintances buy breakfast for you. I didn’t have any acquaintances. The dining room, located at the corner of the U-shaped building, was quite small—just over 100 square meters—but had to accommodate as many as 200 inmates. We’d be squeezed up to those long tables with built-in seatings, and had trouble getting in or out. The dining room was also called a multi-functional room. In addition to dining, inmates would come here for meetings and study sessions.

Unless it was raining, we’d gather in the sports field around 8 a.m. for training. All new inmates had to go, including the half-paralyzed drug dealer who had to be carried down in his wheelchair. I heard he was a gang leader until his enemies damaged the tendons in his arms and legs in a knife attack.

Before going out for training, we’d do counts in the corridor. With more than 200 people cramped up in that narrow space, mistakes were common. Usually the superintendents would scold us before having us do it again.

Outside, we’d do another count. Then the sick and the disabled would be excused from training. The rest of us would run for 20 minutes before queuing up to stand still. It was called standing posture training, the guards would walk around with their batons and hit those who failed to stand upright. After a while, the guards would disperse and drink tea. Inmates would be divided into two groups to train at the command of their superintendents. It would be less hardcore.

Our team’s superintendent was named Cheng Gang. He spoke to me the first day during our breaks. Sentenced to 13 years for fraud, he might be the only superintendent who was here for a non-duty crime. He wasn’t eligible for a commuted sentence because he didn’t return the money. He seemed to hate the locals, telling me that all Yunnan people were “hometown babies” who didn’t see much of the world yet despised people from the outside.

Next to the basketball court was a big banyan tree. As the sun came up in the morning, it cast the tree’s shadow onto the cellblock wall. Then the shadow would slowly move down and reach the first floor windows at around 11 o’clock.

That was when our training would end. We’d do another count and go up to have lunch. Then we were allowed an hour of nap time. I couldn’t fall asleep the first few days. Yang Xiaoze would tell me to get naps in while I could because I wouldn’t be allowed such opportunities after transferring to a new division.

Afternoons were usually for study sessions. The guards would talk about all kinds of prison rules and laws, and ask inmates to repent. Everyone would pretend to be taking notes but no one cared about what they were saying. Before we’d be assigned to new divisions, we’d copy from samples of thought reports, summaries and repentance letters. When there was a particularly wordy guard, we’d miss dinner as he droned on and on.

Every other day, we’d be given some measly amount of meat. Once a month, we’d have bone soup and beef, which was the only time we’d actually get some meat to eat. Normally the new inmates would be the ones to serve food, a tiring job because there were so many people. But when there was meat, the superintendents would be serving food, and they’d first set aside more than enough to eat for themselves—a full bowl, sometimes two—before giving the new inmates anything. Occasionally, Cheng Gang and Yang Xiaoze would spare me some more.

After dinner, we’d rest in our cell. At 7 p.m., we’d sit in our small chairs and watch the CCTV News Simulcast. Then we’d recite the rules and regulations. Occasionally the guards would tell us to go to some meetings. Usually we went to bed at 9 p.m.

Looking out the cell room window, I could see a nearby village, a segment of highway, a corner of a city, and waves of mountains and hills. The small village had about 30 households. At night, only five or six would light up, I assumed the rest of them had left to find work elsewhere. The one house closest to the prison had a red sedan out front. The owner was probably a woman, always dressed in colorful clothings. Was she married or did she have a boyfriend? The hills closer to me had all types of trees on them, including peach trees, pear trees, and mostly gum trees. Occasionally there would be villagers coming with their sickles to cut the gum leaves. The mountains further away looked barren, save for some windmills for electricity. I heard that Binchuan was right behind the mountains. Next to the highway segment was a corner of the city, scattered with some buildings and ongoing construction. On top of the hill in the middle was a strangely shaped water tower. In the afternoon, there would be traffic on the highway. Cars gathered and dispersed, before driving off to somewhere further away. Everything seemed so close yet so surreal.

New inmates with sentences of 10 years or less were required to undergo training for two months, everyone else had three months. Before long, the ones who came ahead of me were reassigned to production divisions and some beds were cleared. Yang Xiaoze saved a lower bunk for me. The upper bunk was taken by a youngster who was in for a traffic crime. Whenever he had time, he’d talk to me about this girl he met online, and how he went to her village to meet her, and how they went to see a concert, and what she was wearing ….

Most inmates were in for drug offenses. The locals were often in for selling, most of them didn’t get long sentences. The non-locals were mostly in for transportation. They’d go to Myanmar, put drugs into a condom and swallow it before returning to China to hand it over to their bosses. Most of them were sentenced to at least 10 years. Many of these people were youngsters from Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou and Sichuan, kids who enjoyed video games. With each job, they made about 20,000 yuan (US$3,000). Jia Nan was from Guizhou, like me. He was in his 20s and was mentally challenged. Once he swallowed two kilos, making him the biggest one-time transporter, a fact that subjected him to a lot of ridicule.

He said, “I was duped. I helped my boss make the trip without even settling the price.”

Once he asked, “Homie, did they (locals) beat you in jail? I was beaten up bad!”

The county jails here were known for abuse among inmates. Non-locals often had it the worst.

Many Yi people were drug transporters. They did large jobs too, and most were given life sentences or suspended death sentences. Abu Xiagui, a man from the Daliang Mountains in Sichuan Province, received a suspended death sentence. Right before we were to be reassigned to production divisions, he asked me to write a repentance letter for him. He said most of his village did this trade. Some had their family members executed; some had their entire family in prison. There was no other option to feed themselves aside from engaging in this trade. In most places, villagers may choose between becoming cheap migrant workers, or committing crimes. Your life was set for you at birth.

That small county town where I went to middle school had quite a few gangs of various sizes, and every year fights would lead to deaths several times. At my school nearly every night after classes a group of upper-crust people stood guard by the gate. Sometimes there’d be gangs, people looking for revenge or to collect protection fees, people flirting. Every time I went through that gate I’d worry about getting messed with. Before junior high, I was the typical obedient child. I studied hard and won praise from just about everyone. After junior high, I left the place where I started my schooling and went to the county seat’s best school. I was shy and didn’t talk much, I was a peasant from the villages. Forget about fighting, I would tremble if I even saw others fight. So, I became a punching bag for some people, bullied all the time. Once when I was sitting in the front of the class, out of nowhere the strongest kid in class slapped me. I’m still not sure why, and nobody ever explained it. I can still remember his face after he hit me, beaming with pride, as if saying “don’t ask why, I’ll hit you when I want.” Incidentally, after I met a few friends, I set up my own gang. We smoked butts, drank liquor, skipped class, fought, and won ourselves a bit of a reputation. Then all of a sudden, all those people who bullied me became different people, heaping flattery on me. This is when I understood the truth: some people like bullying the weak because they won’t pay a price for it. This type of person is almost always strong on the outside but weak in reality, the type to fall after one hit. Resistance is the only way out, this truth I’ve seen verified countless times in my life. It was then that I began to live in a new way.

The prisoners secretly called the division chief Old Qian, as he apparently had some sort of close relationship with the high authorities.

“After you’re here, you aren’t to consider yourself a human being anymore. From now on, you’re the walking dead,” Chief Qian would often say to the prisoners.

For real.

Prisoners would secretly spread stories of Chief Qian’s beatings. Once a ruthless war broke out over some trivial matters, and he suspended a prisoner for three days. When talking to new prisoners, the old inmates showed little excitement or sympathy. They would describe the tortured prisoners as “stripped leather,” and felt that the beaten had all deserved their punishment. Aside from my first day I never saw Old Qian beat any other prisoners, but I could clearly see the fear those old prisoners wore on their faces when they saw Old Qian.

In my first few days Chief Qian called me for a talk. He wore a smile on his face, as if he was a different person. I asked about my case, and he said they don’t care about it, and that if I didn’t cause any trouble here all would be fine. He then proceeded to talk about everything under the sun, from Xinjiang and the Hui, to Sunnis, Shiites, and Hegel …. In the end, he added another rinse to my brainwashing.

“The nation is stronger, the government treats the farmers a lot better—even exempting them from tax. When the prison appropriates land in the nearby village the local farmers don’t argue etc, etc…. The peasants aren’t worth all this.” He seemed to completely misunderstand my situation.

I wanted to tell him that even as a peasant myself I didn’t do it for the peasants, and ultimately I gave up. Many people can’t be convinced. Many years ago that person who would go on to organized crime told me that nobody can change you, only time will change you.

After that Chief Qian called on me several more times, mostly to give me his religious outlook or philosophy, or to recommend that I look around for a philosophy textbook. I took this as an opportunity to ask if I could buy books myself or call people outside to bring them to me. Surprisingly, he agreed.

The deputy warden responsible for reform and the vice political commissar would also call me to talk, to deliver the rough idea that it was my right to not admit guilt but that I must obey the management, and basically asking that we “don’t embarrass each other.”

At the end of the month bank cards and Yikatong cards would be issued. The bank cards were used for people outside to send money for use, and the Yikatong could be used to shop in the prison market. Twice you could go and spend a monthly limit of 300.

In December when the weather turned cold, you had to wear cotton-padded clothing inside. Fortunately it doesn’t rain in Dali in winter, the skies are blue with white clouds every day. Nothing like in Guizhou where the endless fog and rain made people depressed.

I knew that of course, many friends would be writing to me, but for the most part I wouldn’t be able to receive those letters. Perhaps the iron curtain suddenly burst a seam, or maybe the person who distributed the mail had died. Whatever happened, I had received a letter and a postcard with the Eiffel Tower on its front, and the words “More Sunlight!” on the back. It was written by big sister Wang, her and Pipi were now living in Dali and wanted to wish me well, there were many on the outside who were concerned about me.

For someone deep in the dark, this was indeed sunlight.

I immediately wrote a reply to big sister Wang, naively thinking I’d be able to receive more mail.

Of course, the letter I was looking forward to most was Jane’s. Would she write me?

The first time I saw Jane was at the bus station. I took the long distance from Fuzhou to Zhuhai, she came to the station to meet me in an ash blue dress, waved to me on the platform. She never wore makeup and her clothes were simple, she liked British styles. Nearly every other day she’d go out for a run. Back then, we’d cycle to many places, Fenghuang Mountain, Qi’ao Island. Sometimes we’d ride too far, by the time we got home it was already nearly light out. We had no concrete plans, no expectations for tomorrow, just living like that day after day.

By November, new prisoners could purchase things. Cheng Gang suggested that I hold off buying food, that I’d first need a blanket for the cold winter nights we weren’t equipped for. The day for shopping was also visiting day—twice per month, and the only two days we weren’t required to work. All the prisoners were brought to the door of the supermarket to meet relatives or shop.

The supermarket was on the first floor of the second of three concave buildings to the left of the prison gate. This was the teaching building, the other two were prison buildings. You’d see one just about every time you went shopping, a group of feeble old inmates on the roadside, crookedly picking up litter on the field. The supermarket was about 100 square meters, the people selling mostly all duty criminals, the arrogance among them perceptible even from the other side of a thick wall. On the outside they were officials and civil servants, nothing like normal people. Even behind bars their status was much higher than normal prisoners, who were mostly farmers. They hid the better products and sold them only to people they knew well—daily necessities, but mostly fast food that I’d never seen on the outside but that seemed to make people very worried, but maybe nobody cared. At check out I’d exceeded the limit by a lot, so I had to return some items. There weren’t any blankets for sale, so I bought a pair of cotton shoes.

There was another group aside from the new prisoners, the prison art troupe. The inmates called it the circus, and it was mostly made up of people with very long sentences. When they practiced, we could hear the sounds of all sorts of instruments. This reminded me of my never realized rock n’ roll dreams.

Towards the end of November my father came to visit after more than six months. This time it wasn’t because the police were looking for me, but on behalf of my friends. After noting the news from my friends, he again started with the brainwashing, saying the country was growing stronger thanks to there being an eternal ruler, that the government was planning to reinstate his retirement pay …. Fortunately, we only had 20 minutes of meeting time.

When my father was young he was also considered progressive, one of the earliest around listening to Teresa Teng in our region back in the day. Father joined the army and the Communist Party in his early years, then after discharge worked in state-owned enterprises. In the 80s, he was our region’s first person to go on unpaid leave and start a business, before long making a lot of money and was rated one of the top 100 self-employed householders in the country. My mother became a National Women’s Day Flag-bearer, often traveling to Beijing for meetings. It was great for a while, officials from county and provincial ministries would often come to visit her at home. Each time an official came it was as if our family was on holiday. My mother would start prepping meals in advance, and get so busy she had to hire a babysitter.

My parents liked to help others, and the people in the village received that help often. Back then, they paid for the village electricity and water to be installed. After the power was on, my father went to a friend in Beijing and bought the best TV and VCR available, a Panasonic. The first day the TV was installed nearly the entire village came out. The signal was so bad that someone had to move the antenna up to the roof ….

But good things don’t last forever. My father’s temperament is very straightforward. and he offended some officials. In the 90s his farm was meddled with by the government and collapsed, and thus began his endless career petitioning ….

Before assignment, a very amiable guard and Yang Xiaoze brought us to a classroom full of computers for a psychological evaluation. The computer asked me some questions, but I didn’t get to see the results.

Two months flew by. Before being assigned, every new prisoner had to write out a confession letter and denounce their crimes, thank the government and Party, and swear to reform and lead a new life. I told Yang Xiaoze ahead of time that I wouldn’t admit guilt or write the confession letter.

Chief Qian told Yang Xiaoze to review my past, which I expected.

“I hear you didn’t write a confession letter?” Chief Qian asked.

“I’m not guilty,” I said.

A few policemen came back to surround me.

“If you don’t write it, we can’t commute your sentence. This is for your own good,” he said again.

“Don’t commute my sentence,” I said

On this I never shook, and was mentally prepared for whatever situation might come.

Chief Qian went on: “Well, you don’t have to confess and repent, but just write that you plead not guilty but promise not to violate prison regulations.”

I thought about it and agreed, since he’d helped me get books in.

The older prisoners told me that there’d been people who pled not guilty before, and they’d all been tortured cruelly. Apparently, I should consider myself lucky.

Days before assignment, the new inmates busied themselves trading contact information. I had no address or phone number to leave. Others gave me theirs, and I politely pretended to leave mine. I knew in my heart that I’d never see them again.

When the others told me that “the good days were over,” I didn’t take them seriously.

Up to assignment day Chief Qian still hadn’t lived up to his promise about the books. A few dozen of us, carrying our bedding, clothes, basins, and snacks, were taken to the field at the supermarket entrance, then were led away successively like animals at market. Everyone was first stripped naked and inspected. I was in the last group to be taken away, sent to Cell Zone Four.

Zone Four was the clothing production prison ward. Since all the prisoners were in the workshop during the day, the guards took us there first. The workshop was on the third floor, with rows of different types of sewing machines, hundreds of them, and behind each machine was a prisoner with a face twisted in hardship. To the left of the entrance was the guard office with a big official desk outside with two officers napping on it. After registering I was assigned to a team. An attendant led me to a sewing machine, pointed to it, and said it was going to be mine in the future. He then sent me some accessories and a cloth and told me to get to know the machine. Older criminals wouldn’t stop coming by and striking up conversation, boring people.

The workshop bathroom was at the most interior position. It had just two basins with no sort of cover, and was always overcrowded. Like a bus during rush hour, those inside couldn’t get out while those outside couldn’t get in.

Lunch was eaten in the shop, with prisoners squatting in groups to eat in the small open area outside the office and bathroom. A couple other inmates came up to ask about the new cotton shoes I had bought.

Work would end after 7 p.m. Before calling it a day we would line up for the officers to search us one by one. After the search, we’d go downstairs in order, line up again, then return to our cells shouting slogans, everyone timid and careful. If there was a problem from one person, the officers would punish everyone, then a group of prisoners would later abuse the troublemaker.

My cell had changed from the sixth floor of the original building to the first, and my bed was now the upper bunk, the lower reserved for older and connected prisoners to sleep on. My cellmates were relatively friendly, asking about the details of my case. I had no way to explain it to everyone, so I just said the charge the court gave me. Frustrated, I thought of the dialogue between Andy and Red in “Shawshank Redemption.” Andy said he was innocent, to which Red replied, “Everyone in here is innocent.”

Like the entry supervision team, the team leader slept in the first bed, and a duty officer also slept in the jail unit. Everyone was exhausted and crawled right to bed. But, since we’d just changed beds, I couldn’t sleep.

“The sole happiness here is sleep,” said Zhu Li, who was sleeping across from me. Zhu Li was also from Guizhou, and like most others here, was involved in drug smuggling. His parents worked in Guangzhou and he was brought up there. A stack of photos sent from home showed him with fancy cars and beautiful women.

At 6 a.m. we’d have to get up and hurry to queue to wash, use the toilet, and eat breakfast. When work started at 7 a.m. it was still dark; when shift ended, it’d also be dark. Except for a little bit leaking in the window in the afternoon, you generally couldn’t get any sun. Sometimes after work the officers would hold meetings. There was basically no free time, and when there occasionally was we’d already be exhausted.

Sometimes people from my hometown would come visit to chat, teach me about the sewing machine, or gift me little snacks.

There were 110 in the whole squad, many of them serious criminals. Aside from the duty staff—production team leader, trimmers, Chief Inspector, those putting orders together, machine repair, etc.—over 70 people were left to pedal the sewing machines, the hardest job there. We mainly made all types of overalls, with each single pair made by a series of processes, not difficult but a serious task. The prisoner in charge, the production team leader, basically managed the production. The guards didn’t understand, none of them would learn about the sewing process. In prisons that aim to make money, these prisoners can sometimes be more powerful than some of the officers. Inmates who wanted to be commuted needed a high output and a high assessment score, and then their sentence would be commuted fast. A good relationship with that leader was very important for ordinary prisoners, who flattered them and offered them gifts in private. If the team leader didn’t like you, they’d embarrass you all the time and give bad reports on you. If the officers just scolded you a couple of times you’d be lucky; more often they’d hit you. Like this, some prisoners would slack off all day long and still get high scores, then quickly be commuted. For others, no matter how hard they worked, they couldn’t finish their tasks, their sentences were reduced slowly, and they were often given trouble by the officers.

I counted as an exception, unwilling to admit guilt or ask for a shorter sentence, not to mention kiss ass. Wang Yi came over and said to me, if your sentence isn’t going to be commuted, just sit here and go through the motions, that’s fine. If you see guards coming just pretend to press the pedal on the sewing machine.

“Those idiots can’t tell,” he said.

Wang Yi was a bit over 50, in for life for selling drugs. This was already his second stint in jail, this one for dealing while on probation. He’d got essentially no hope for parole since he’d also “had a couple incidents” while in prison, so even though he’d been in for six years, he’d still got who knows how long. Sometimes people asked him, think you’ll make it out alive?

Wang Yi and I were cellmates, and he would occasionally tell me stories about resisting the guards.

“I’m not afraid of them beating me, but I am afraid of them hanging me!” he said.

“As soon as you’re hung up there you start screaming,” said Zheng Long, who slept on the bunk below me and was always teasing Wang.

“That son of a bitch instructor from before was ruthless, hung me all the way up on the door,” Wang Yi tried defending himself. He was one of the famous people of Zone Four. He didn’t care about the supervisors at all and, most of the time, the guards didn’t try to control him either.

“To hang” is a type of torture popular in prison. They cuff a prisoner’s hands behind their back over the top window sill so that their tiptoes can just brush the ground. Normally they leave people hanging for half a day or more. Few can last a whole day. Most quickly admit their wrongs and beg for forgiveness.

Listening to the older prisoners’ descriptions, a faint dread stirred in me. Thinking back to my previous clashes with the guards, I hadn’t been particularly afraid—but terror can be infectious. It seeps out of everyones’ eyes, expressions, and speech, filling up the air and eventually digging into your heart. More dreadful than torture is the terror that pressed down on you every second of every day.

In there, the guards were the law. For any small thing, they could arbitrarily punish you: make you hand-copy the rulebook, goose step in place, or engage in some other form of punishment they think might bring joy to their boring day. Those punished had to rejoice—after all, it was better than a beating from the guards. Hand-copying the rulebook was decidedly not a light punishment. It meant that within a short timeframe, you had to spend your already extremely rare rest hours writing out boring characters. Some prisoners didn’t finish even after a month of copying ….

The first and second months went pretty smoothly. Midway through them a group of young guards sought me out to ask a few questions:

“Why did you want to do this (meaning Not News)?” one of them asked me.

“For myself,” I said.

“Well, at least you’ve got self awareness,” he said. Maybe that was the answer he had wanted to hear.

“For your case ‘picking quarrels and provoking troubles’ doesn’t really fit. But you definitely did something illegal, otherwise the PSB wouldn’t have arrested you,” the other junior captain said.

People always search for reasonable grounds for their actions. Usually, police believe they’re enforcing the law even when they’re beating or abusing prisoners, in this way their hearts don’t become conflicted. Of course they aren’t willing to believe that innocent people are locked up in their prison. Even if they feel the charge “picking quarrels and starting trouble” is absurd, they’ll still think “you’ve definitely done something else, it’s just the evidence hasn’t been found, that’s all.”

My third month after arriving in Cell Zone Four was also the month before Chinese New Year, and my production targets were crazy. I couldn’t finish them, so I had to hand copy the rulebook ten times. I didn’t want to do it, but every other person had that punishment, so I told myself “they’re all copying, why can’t I copy? It’s better than getting hung up, isn’t it?”

By the time I finished copying, I regretted it.

I went to Wei Liming, the ward instructor. “What you’re doing to prisoners is corporal punishment in disguise,” I said.

“You’ve already finished copying, what’s the big deal? We’ll talk it over anyway.” Wei Liming had also just been transferred here from the newcomers’ ward, and had sought me out for a chat before.

Wei Liming was a talker. When he led classes for the newbies, they often ran long. Because he didn’t get along with Chief Qian, he was assigned to Zone Four. In Zone Four it wasn’t required to hold class for the prisoners, but he still found opportunities to use up all the inmates’ free time leading meetings. At his peak, he called six days of meetings in a single week.

By New Year, the cells didn’t see much sunlight and were very cold. Luckily I’d already purchased a blanket—if I hadn’t I’d have been woken by the chill at night. A couple of days before New Year’s Day, my long underwear went missing. I looked for it all over the drying room but couldn’t find it. About 200 people used the 100 square meter room to dry identical prison garb, so it was common for people to pick up the wrong clothes. Anyway, everyone had only two pairs of underwear. If you lost them the guards didn’t care, and they wouldn’t sell you new ones either. All you could do is endure the cold. I needed to seek out the guards, and so I found Wei Liming.

“First go search for yourself, then we’ll talk,” he said.

“If I can’t find it, will you sell me a pair?” I asked him.

“Can’t do it, I’m not in charge here, there’s a department specifically responsible for this.” He brushed me off.

On the day of Spring Festival, everyone was busy celebrating. The prisoners were occupied by all sorts of prize games and the guards were simply hoping to finish early and return home to welcome the New Year. I was still looking for my underwear unsuccessfully, so I once again sought out Wei Liming.

Wei Liming immediately turned on the PA system and commanded all prisoners to lay out their clothes in order to help me find mine. I immediately regretted asking him, if I’d known it would be like this I wouldn’t have. That guy clearly aimed to make all the prisoners hate me—some had already started cursing, but I swallowed my rage. Not long after, my clothing was found (I guess the guy who took it by mistake turned it in), Wei took my underwear and, immensely proud of himself, walked over to me and said loudly:

“Inmate Lu Yuyu, it’s clear your clothing was never lost, and that you set this up to hassle the guards and disrupt the prison’s orderly management. According to regulations, you will be demerited.”

“Demerit away! Better yet, lock me in detention! As for the clothes, I don’t even want them.” Maybe I’d choked it back for too long, all of a sudden I exploded, took the clothes, and threw them on the ground.

All the nearby prisoners gathered around me in shame, suddenly speechless. Out came the handcuffs, my arms were locked up above a window, and the guard walked away.

Not long after, two young guards came out. They wanted me to calm down and admit wrong. I didn’t answer them, so they called an orderly, Fu Jing, to stand by my side for some brainwashing, mostly along the lines of, “When you’re in a hole stop digging.” Fu Jing once lent me a bottle of vitamins, so our relationship wasn’t half bad.

All my cellmates were already watching the CCTV New Year’s Gala. Now and then their laughter would ring out. Fu Jing saw that it wasn’t working, and went off to go find Wei Liming.

“The instructors say today is New Year’s Day, so they won’t demerit you. But you must write a self-criticism, otherwise Wei’s reputation won’t survive,” Fu Jing said on his quick return.

The air was cold and my legs were already stiff. I hesitated for a moment and then agreed.

This was my first time writing a self-criticism since being imprisoned. Once again I was in charge of myself for an extended period. Can time really change a person?

I don’t usually celebrate holidays, Spring Festival included. But from the point of view of an imprisoned human sewing machine, the holiday means you can relax for three days, eat a bit more meat than usual, and even enjoy some sun. In Dali, the winter sun is so warm.

During Spring Festival in 2014, Jane didn’t return home. The months before were our busiest of the year. Every day we could find an unquantifiable amount of information: endless searching, editing, downloading, uploading. There was no time to think of celebrating the New Year. The “National Treasures” came for a visit, two of them looking for me to write out a statement and warning us not to publish again. I told them, “If I’ve violated your laws then you can arrest me.” Jane yelled at them. A few days later, our landlord came to us demanding that we move. Soon, strangers began arriving at our doorstep pressing us to move out. Just a few days after the end of the year, someone took a knife to hack the water pipes downstairs to pieces. Where could we move? After talking it over with Jane, we decided to go to Dali. We’d been there before and liked the climate. It’s cheap, and the countless tourists would make us stand out less, allowing us to avoid most harassment.

Xiao Bo’s bed was next to mine, but he rarely spoke with people in our cell. But after I fought with Wei Liming, he started to talk to me whenever he felt like it, or when passing by me he’d throw some waste cloth at me. We quickly became close. One time, taking advantage of the opportunity afforded him while cleaning, he brought me into the ward’s little library, and we surreptitiously took a bunch of books including “A Pictorial History of Europe,” and “Chronicles of Napoleon.”

Xiao Bo told me he’d been beaten by the guards there before, and had continued to report the guards who beat him to the supervising officer. He asked me whether writing a letter to the provincial prison administration might be of use. I said, “As far as I can tell, it‘s pointless. Your letter won’t even get sent out. If you consistently bring complaints, the guards here won’t like you, so you won’t get assigned an easy job and it’ll be difficult to finish your production quotas.” Not long after, Xiao Bo was assigned to a different ward.

Starting in my fourth month, Zone Four rolled back a rule and inmates no longer had to copy prison regulations if they failed to complete their tasks.

There were three madmen in Zone Four: Xiao Ye, Wu Tian and Zhang Kui.

Xiao Ye’s sewing machine was right next to mine. He’d never stop talking to himself while working. One morning when we gathered in the basketball court before going to work, all 400 of us were squatting down at our spots on the concrete, but Xiao Ye didn’t. He was standing there like nobody was watching, making all kinds of traffic cop gestures and murmuring. All the inmates and guards must have grown used to him, no one even cared what he was doing. Xiao Ye would get out in a few days, then the news would come that he was locked up again in a mental institution for setting his own house on fire.

“That’s normal. It would be weird to stay sane after being locked up here,” some inmates said.

The other two who wouldn’t stick around were Wu Tian and Zhang Kui. Wu Tian was in a team behind mine, and he’d yell something at the air. I couldn’t tell what it was because we were far apart.

Zhang Kui was also in a different team, but he was more recognizable. Even from far away you could easily recognize Zhang Kui, who had to bend down and walk in small steps. Zhang Kui was always wearing a straitjacket, as if he and that blue denim instrument of torture had merged into one. He had to sleep in it too, so taking a shower was out of the question. There was always a yellow mark on his butt. It smelled like a dead animal from afar. It probably wasn’t easy for him to use the bathroom either. The inmates despised him, scolded him all the time. He wouldn’t shoot back or stop talking to himself. His face, never cleanly shaven, would twist up and seize. Zhang Kui refused to work. He’d sit on a small stool while others worked. The guards would arrange other inmates to look over him. Occasionally, some bad tempered guard would punch him or kick him. And at one point, the guards invented some new game: they made a black cloth that would cover his head except his mouth, and looking for some fun, the superintendents would put a peanut or some other things through the hole, and have a good laugh looking at him chewing.

Zhang Kui used to be a superintendent too. Some would say that he somehow pissed off the guards; others said that something happened to his family before he went crazy. He tried to kill himself several times. His cellmates were punished together with him. So inmates started to ostracize him and often cursed him. Many people thought he was faking it. Some told me that they admired Zhang Kui because he could fake it for so long. I felt sorry every time I saw him. I didn’t know if one day they’d put me in a straitjacket too. And if so, what would I do? I wouldn’t allow myself to live like that. It’s better to die than to be tortured and ridiculed, left with no dignity.

Because I had no pressure for production tasks, I’d mostly slack off at work and listen to people chat. Jia Nan (the one who swallowed two kilos of drugs) was also locked up there, not far from me. He was also possibly mentally challenged. I heard that the bosses were specifically looking for people like them to do transport. The bosses seemed to be safe: there were many inmates locked up for transporting drugs, but so far none of their bosses were thrown in there.

Day after day, we went to work and came back. The weather was getting warm. Cherry blossoms bloomed and withered away, their fruits growing bigger and bigger. Then all of a sudden, the guards told us we’d be having three days off starting May 1. Everyone was ecstatic, this had never happened before. Some cellmates said this meant that the nation was wealthy enough to not have to earn money from prisoners. I wasn’t in the mood to argue. Our paths were straight lines crossing briefly before parting ways, I saw no point in wasting my time.

There was bad news, too. Starting in May, inmates that failed to complete their assigned tasks would be punished with additional drills.

The first time I saw him beating someone up, I knew for sure that one day I’d have conflict with Little Mute. Little Mute was a guard assigned to the prison a few years ago. His speech was slurred, and inmates called him Little Mute in private. Little Mute was was the chief of Team Four, before getting reassigned to Group One with a demotion after he beat up an inmate. He wasn’t happy about it and often took it out on the inmates, a few had been smacked by him already.

The first time I walked up to Little Mute to tell him my machine had broken down, I was propelled by a desire to overcome my fear of him. It was hard to bear. And the clock continued running while the machine was being fixed, meaning we could do less work—although that didn’t matter much to me.

Little Mute reacted somewhat normally, asking me to go back and wait. I waited for a long time, but no one came for repair. So, I went up to him again.

“Who do you think you are? Lu Yuyu, if we were outside, I’d have killed you already!” He looked like he had eaten explosives for lunch.

“My machine broke down,” I repeated.

“Your organization has given up on you. Don’t think too big of yourself. Now get lost!” He cursed while gesturing his water cup towards my head. I could feel my blood boiling. As soon as his water cup touched my forehead, I bowed down, my fingers pointing to my head, and said to him:

“Come, kill me now, I’ll despise you as long as I’m alive!” I said this for no real reason.

Little Mute was stunned. As for the superintendents, they for sure wouldn’t give up such an opportunity to lick a guard’s ass. They jumped at me and bent my arms back. Little Mute then cuffed me up, pushing me towards the guard’s office. I was worried that he’d “hang” me at the window. Fortunately, the chief of Zone Four and a group of guards came out. They saw me and pulled Little Mute away before cuffing me by the window.

The division chief was young, and reportedly had good family connections. He seldom appeared in front of the inmates or handled things by himself. At meal time, the guards asked superintendents to bring me food. I was too mad to have an appetite. Then the guards came, one after another, asking me to eat. I skipped two meals, anger suppressing my appetite. In the evening, the division chief came by.

“I know about you. I think you are really something for what you’ve done. Don’t get mad over such trivial matters, alright? And, don’t let things go all the way up the management.” He said.

“It’s wasn’t a big deal, sure. But if I didn’t fight back, that guarantees it will happen again.”

“Alright. Tell me what you want.”

“I want this stuff to stop. And, I was promised that I could buy books. I want my books.”

“That’s it? OK then, no problem. Will you eat now?”

“Sure.”

It looked like things were resolved. Most importantly, I was allowed to buy books.

Little Mute was not giving up. He wanted to win his pride back. Three days later, he asked the production manager to have me reassigned. Being reassigned at that moment would all but ensure that I’d get punished for not being able to complete my tasks. I refused. The production manager said that he was helpless. I said, don’t worry, I can take care of it myself. Although I was only here for a few months, the production manager took care of me by giving me some easy tasks. Maybe he did this because he saw that I dared to push back against the guards.

I went to Little Mute directly. Having learned his lesson, he didn’t curse at me. He said with a smile, “It’s within my power to reassign you.”

So, I staged another hunger strike. I just sat there and refused to work. In the evening, the deputy division chief came and said that the chief was out of town and had asked him to come check on me. I said that they broke the promise, that my only demand was to be transferred to a different division. The deputy chief tried to strike up some chit chat before realizing that there wasn’t much else to talk about and leaving.

After I skipped my fourth meal, my transfer paper was issued. A few young guards came and asked me to pack my stuff. They looked like they were about to tear me up. But I didn’t care anymore.

(To be continued) [Chinese]

Translation by Yakexi, Josh Rudolph, and Joseph Brouwer.