Chinese authorities have long claimed that the Islamic State is actively recruiting Muslim Uyghurs from the country’s northwestern Xinjiang region. In December 2014, Global Times reported that 300 Chinese Uyghurs were fighting alongside the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Although it remains difficult to verify exactly how many Uyghurs have left China to join the terrorist organization, a new report released by a U.S. think tank on Wednesday suggests that more than 100 Chinese Uyghurs have done so between 2013 and 2014, many motivated by a desire to find “a sense of belonging.”

A July 20 report from New America, a think tank in Washington, DC, examined more than 4,000 registration records of fighters who joined the Islamic State between mid-2013 and mid-2014. These rudimentary questionnaires asked basic questions of each fighter, including origin, travel history, level of education, former employment, and previous jihad experience. Analysis of the records revealed that at least 114 Chinese Uighurs, a predominantly Muslim Turkic-speaking ethnic group concentrated in the northwestern Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang, entered Islamic State territory during that time period. Nate Rosenblatt, the author of the report and an independent Middle East/North Africa researcher, obtained the data from contacts made during his previous research in Syria.

[…] The Uighurs in the sample were entirely new to jihad. When asked if they had any previous experience with jihad, 110 of the Uighurs replied that they had not; the other four left the question blank. Seventy percent of respondents indicated they had never left China before embarking for the Islamic State. Rosenblatt said this suggests the fighters are not part of “traditional Islamic separatist movements that have existed in China for some time,” such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a Uighur separatist organization that China and the United States have labeled a terrorist organization. […]

The lack of previous experience with jihad and the implied lack of contact with ETIM suggests that “it may not be that these fighters are as religiously motivated” as some fighters with origins elsewhere, said Rosenblatt, but rather that the they are looking “perhaps for a sense of belonging that they don’t get in China.” The Islamic State has targeted Uighurs with slick propaganda videos showcasing orderly classrooms full of children studying the Quran. “That is exactly what a lot of these fighters are looking for,” said Rosenblatt. [Source]

A recent story from Invisibilia focusing on radicalization among Muslims living in Denmark suggests a search for acceptance may also be driving IS recruitment from elsewhere. AFP has more on the characteristic of Islamic State recruits from Xinjiang:

Overall, recruits were more likely to come from “regions with restive histories and tense local-federal relationships”, the report said.

The nominally autonomous Chinese area offered IS rich recruitment potential due to “significant economic disparities between the ethnic majority Han Chinese and the local Uighur Muslim population” and “substantial state repression”, it said.

[…] On average, the fighters from Xinjiang were less educated, less well travelled, and more likely to be married than others who sought to join IS. They also claimed only a low level of religious training.

The data included a number of registration forms for children, including one as young as 10, the paper said, and “several of the forms for these children explicitly stated they joined ISIS with their families”. [Source]

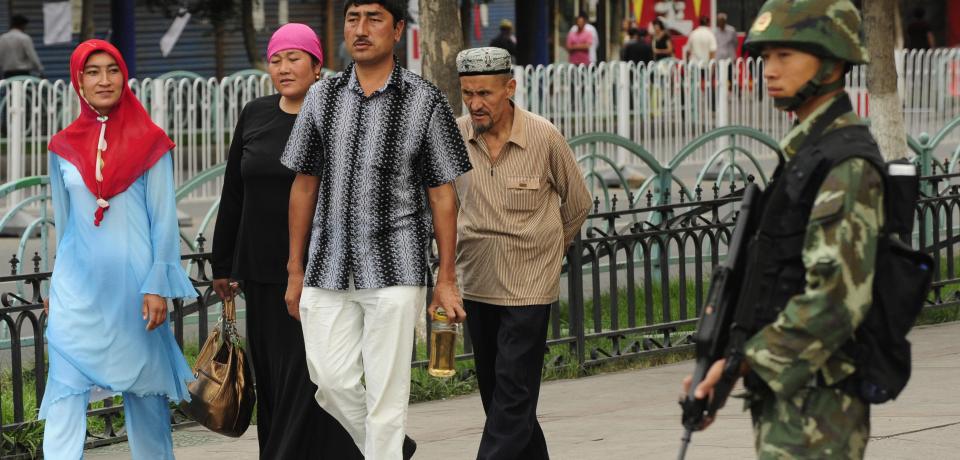

Tough religious restrictions in Xinjiang may be a major factor driving Uyghurs to join the Islamic State. In recent years, authorities in Xinjiang have implemented a number of policies to curtail the observance of Islamic practices such as fasting during Ramadan, wearing headscarves, and growing beards. All of these restrictions have taken place while Beijing maintains that Uyghurs in China enjoy “religious freedom.”

Meanwhile, hundreds have died in a series of deadly attacks in Xinjiang and elsewhere in the country over the past several years. Authorities have consistently blamed the bloodshed on religious extremism and radical Islamist militants with alleged ties to the global jihad movement. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), a Uighur separatist organization, has been regularly accused of being behind the wave of unrest by Chinese authorities, and the organization has laid claim to several attacks in China in recent years. However, foreign experts and activists have disputed the validity of ETIM claims, or questioned whether the organization is as organized as Beijing asserts. Reuters reports that the group has been recently added to Britain’s official list of terrorist organizations.

Elsewhere, James Palmer at Vox writes that the Chinese government nevertheless has political incentives to maintain peaceful relations with the country’s Muslim population.

The past decade has seen distrust of Muslims spread beyond Xinjiang to a much wider swath of China, as James Leibold, a political scientist and senior lecturer at Australia’s La Trobe University, recently noted in a paper for the Jamestown Foundation.

[…] Yet China’s Muslims are unlikely to face wide-scale persecution — at least from the government. Even as the authorities cracked down in Xinjiang over Ramadan, Leibold noted to me in an email that the central government had issued notices calling for officials to “respect and uphold the cultural customs and legal rights of ethnic minorities” and redoubled propaganda efforts (such as the white paper) to preach China’s tolerance of religious freedom.

Unsurprisingly, Beijing is doing this not out of concern for religious rights but for political ends. Beijing is currently pursuing an ambitious geopolitical plan known as the “One Belt, One Road” initiative. […]

[…] To make it happen, China needs the cooperation of a whole bunch of countries — including a substantial number of Muslim ones. This means the central government in Beijing has a pretty strong incentive to make sure it’s not perceived as persecuting Muslims all over China, as that would almost certainly infuriate many of its Islamic partner nations. [Source]

Read more about the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, or the varying degrees of religious freedom enjoyed by Muslims of different ethnic groups in China, via CDT.