“Anyone who has ever tested positive is not wanted.” “No tattoos, criminal record, or positive test history.” “Applicants who have tested positive or been in a mandatory quarantine facility need not apply.” “During the pandemic, cannot have been in a temporary government shelter, fangcang field hospital, or mandatory quarantine facility. Penalty for lying is docked wages + a fine.” Shanghai’s online and offline job recruitment boards have been filled with such caveats recently, making it difficult for workers to find jobs if they have ever tested positive for COVID, been quarantined, or worked as pandemic volunteers.

Screenshots of online ads, all of which refuse to consider applicants who have tested positive for COVID-19 in the past. The ad at left is punctuated with a cheery “sun” emoji (the Chinese character for “positive” also means “sun.”)

Left, underlined: “No tattoos or criminal records. Nucleic acid test result within the last 48 hours required. Those who have ever tested positive are not wanted!”

Top right, underlined: “Nucleic acid test result within the last 48 hours required. Anyone who has ever tested positive or been in a fangcang field hospital need not apply.”

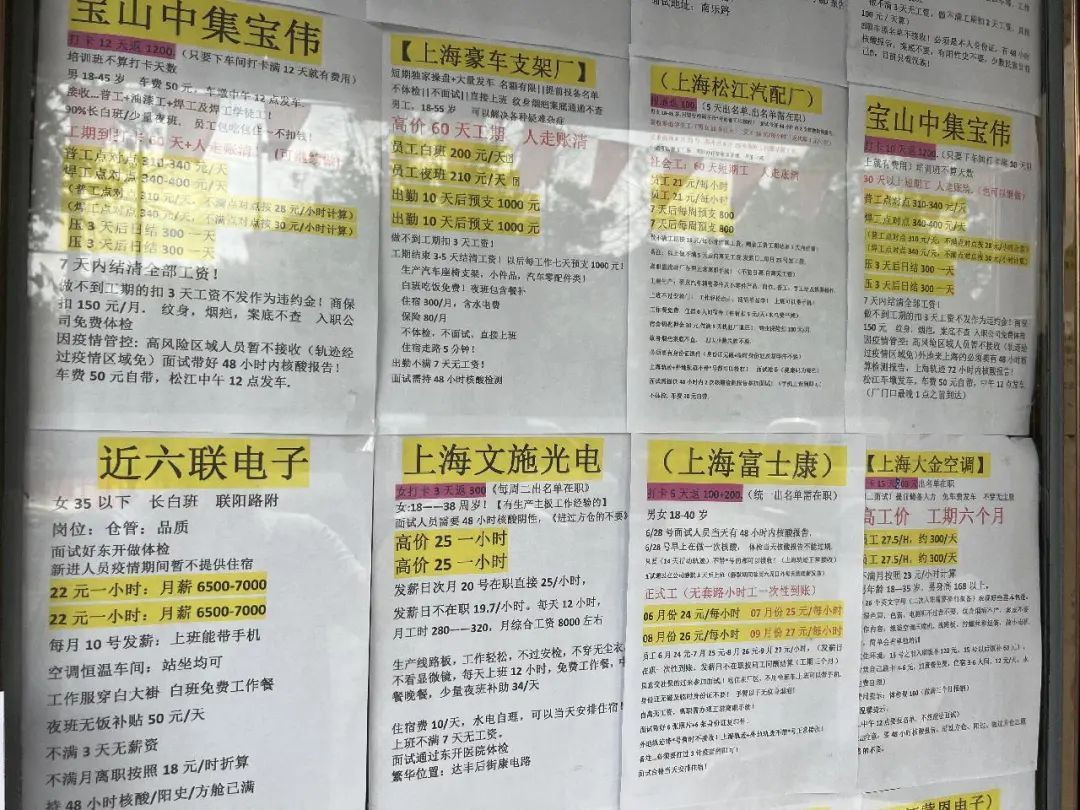

Job listings in Shanghai include various other pandemic-related requirements and caveats.

Top, far right: “Due to pandemic prevention policies, we are temporarily unable to accept applicants from high-risk areas.”

Bottom left: “During the pandemic period, we are temporarily unable to provide housing for new recruits.”

Bottom, second from left: “For interview, applicants are required to have a negative COVID test taken within the last 48 hours.”

Recent reporting from Shanghai about discriminatory job ads and the high unemployment rate among former COVID-19 patients and pandemic volunteers has drawn national attention to the problem of COVID-related discrimination. Viral images of unhoused individuals, many of them migrants, sleeping in train stations, living in public restrooms, or stowing their belongings in garbage bags have elicited widespread sympathy on Chinese social media. Meanwhile, screenshots of blatantly discriminatory job postings have touched off public anger, official condemnation, and a spate of op-eds by state media decrying discriminatory recruitment and hiring practices. These high-profile reports of discrimination have also prompted citizens and experts alike to re-examine stigmatization and discriminatory language, to call for punitive fines against companies and recruiters who practice discriminatory hiring, and to suggest educational campaigns and legal reforms to reduce discrimination on the basis of a person’s health status.

Unhoused individuals sleeping on the floor of Shanghai’s Hongqiao train station

Sleeping in a row of chairs below an elevator

Unable to return home, some migrants take shelter in a train station shopping area.

Using cardboard boxes, plastic garbage bags, and a luggage cart to form a makeshift shelter in a public area

On July 3, the Chinese-language Shanghai Morning News published an investigation into COVID-related discrimination by job recruiters. The piece focused on the travails of three migrants (referred to by pseudonyms) struggling to find jobs and housing after having recovered from COVID-19. Chen Feng, who was infected with the coronavirus while working in a fangcang field hospital, sleeps on cardboard boxes in the basement of a Shanghai office building by night, while attending job fairs and searching for job listings on WeChat by day. After being turned away by many job recruiters because of his former COVID-positive status, Chen posted about his experience in a WeChat group for former field hospital workers, and discovered that many had encountered similar discrimination. His friend Liu Shuo, who also contracted COVID-19 while working in a field hospital, is searching for a steady job while living in a tiny room he rents for 800 yuan (approximately $120 U.S. dollars) per month. Liu was initially apprehensive about telling his landlord that he had tested positive for COVID-19 in the past, but he felt obligated to do so: fortunately, his landlord allowed him to stay. When Liu’s friend Zeng Ming, another former COVID-19 patient, meets with recruiters about jobs, they often respond with “How dare you come here to apply for a job after you’ve been in quarantine?” Zeng is hoping to find a position at a factory, but has been discouraged by recruitment advertisements, even for large employers such as Foxconn, that stipulate, “Anyone who has tested positive or been in mandatory quarantine is not wanted.” When a reporter from the Shanghai Morning News followed up by contacting numerous local job recruiters, they were told, “Companies like Disney, FoxConn, and Daikin don’t want people who have ever tested positive for COVID-19.” Following the publication of the report, the named companies denied that they had discriminated against—or instructed intermediaries to discriminate against—applicants who had tested positive for COVID-19. The “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases” prohibits employers from discriminating against individuals who have contracted or are suspected of contracting infectious diseases.

The following week, the Chinese-language Southern Metropolis Daily published “The Ones Who Recovered from COVID-19: Driven Out, Discriminated Against, Discarded,” a long-form article featuring personal stories of employment and housing discrimination, and interviews with medical and legal experts about the causes and questionable legality of such discriminatory practices. A popular science blogger quoted in the article argued that hiring practices that exclude former COVID-19 patients are an outgrowth of China’s uncompromising “zero-COVID” policy:

In a recent post, popular science blogger @庄时利和 (Zhuang Shilihe) wrote that employers who restrict recruitment of those who have recovered from COVID-19 are not simply acting out of medical ignorance, but are likely taking into account the actual risks. If an employee tests positive, or tests positive after previously testing negative, the entire company or factory production line could be shut down. Once production stops, the company will face huge financial losses, and these losses will be shared by other employees of that company.

[…] “China has always had guaranteed legal protections (such as the Law on the Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases and the Employment Promotion Law, among others), but the difficulty lies in their implementation. The issue of discriminatory recruitment by businesses is essentially a problem of excessive demands from the top being piled on those at the bottom—those who implement the policy on the ground. If there is no substantive punishment for issuing these excessive demands, the problem will only continue to be compounded,” Zhuang Shilihe wrote. [Chinese]

These media reports were followed by an explosive July 11 WeChat article about a female migrant named Afen, who was reduced to living in a public restroom at Shanghai’s Hongqiao railway station after having contracted COVID-19 and being turned away by potential employers. The now-censored Chinese-language article “I’m Hiding in a Bathroom in Hongqiao. I Don’t Know Where Else to Go” (archived by CDT Chinese editors) was illustrated with photos of people sleeping in the railway station and screenshots of job postings excluding anyone who ever tested positive for COVID-19. Writing for SupChina, Zhao Yuanyuan described the WeChat blogger’s viral article, and the response it drew from the public and the Shanghai government:

“Afen’s case is not unique. Many of the migrant workers she met at the station are facing the same situation.”

[…] “Some of them manage to find work on a day-to-day basis for logistics companies, food-delivery platforms, and warehouses. But the only way to do that is by concealing their history of COVID infection,” the blogger says, writing that he was concerned about these migrant workers’ health and safety as a heat wave scorched Shanghai in the past few days.

After the story went up on Monday, Chinese social media users — especially those that are in Shanghai — were quick to empathize with Afen’s hardship and called for an end to discriminatory hiring practices targeting recovered COVID patients. “Looks like it’s not the virus that’s making life miserable for some people. We are facing a human problem,” a Weibo user commented (in Chinese).

[…] In response to the criticism, Shanghai government spokesperson Yǐn Xīn 尹欣 stressed (in Chinese) at a COVID briefing this afternoon that local government departments and companies should “treat recovered COVID patients equally and fairly.” But no specific policies or measures addressing the mistreatment of migrant workers have been announced. [Source]

In response to this local reporting and social media content, there has been an outpouring of opinion pieces by state media decrying COVID-related employment discrimination, but offering little in the way of concrete solutions. A strongly-worded July 6 China Daily op-ed proclaimed, “Like any form of bigotry, COVID discrimination must not be tolerated.” An opinion piece in the Global Times, published the same day, emphasized the illegality of COVID-based discrimination under Chinese law, repeated the denials of several large companies that they had discriminated against COVID-positive applicants, and touched on the topics of Hepatitis B discrimination and the need for “substantial punishment” to deter “law breaking behaviors of companies, labor dispatch companies or job agencies.” Shanghai Daily’s English-language website Shine reproduced the talking points from Yin Xin’s July 11 COVID-19 press briefing, and reiterated the existing legal protections for workers under Chinese law.

A recent Caixin article by Wang Xintong and Bao Zhiming described the Shanghai government’s anti-discrimination warning to companies, the protections afforded by current employment laws, the scientific facts about coronavirus transmission and reinfection, and the response from businesses and social media:

On social media, users have called for specific measures to help recovered patients return to work and punish businesses discriminating against them, saying the government’s Monday statement to the Covid-related discrimination does little to help recovered Covid patients.

Business owners told Caixin that enterprises had avoided hiring recovered Covid patients because doing so might hurt business operations. If a recovered patient again tests positive for Covid-19, all employees of the same company will be identified as closed contacts and put under quarantine for two days, significantly impacting the company’s normal operation and production, the owners said.

However, a disease control officer told Caixin that companies don’t need to worry too much as the rate of reinfection in recovered patients is low.

Shanghai has seen Covid-19 cases climb in the past week after detecting the more contagious BA.5 sub-strain of the omicron variant. The flare-up renewed fears of a setback to the city’s reopening just as its 25 million residents emerge from a two-month lockdown. [Source]

Stigmatization of and discrimination against those who have recovered from the coronavirus in China is not a new phenomenon, nor will it be easily abolished—not without substantial punishments and fines levied against employers and intermediaries who discriminate on the basis of COVID status. According to the World Health Organization, China has had nearly 5.2 million confirmed cases of COVID-19—small as a percentage of the population, particularly compared with infection rates elsewhere, but still a huge number of people. It seems likely that many of these individuals—like those before them with HIV, Hepatitis B, SARS, or other communicable diseases—will continue to be stigmatized and denied access to jobs, housing, opportunities, and equal treatment.

In 2020, journalist Xiao Hui wrote about his personal experience with COVID-19 and the stigmatization that he and his fellow patients faced after being released from hospital. Xiao Hui’s now-deleted WeChat post “Recovered COVID-19 Patients, in Their Own Words: The Suffering Has Only Just Begun,” archived by CDT Chinese editors, included the following plea:

We have already suffered physical and mental harm. I hope that our society can attain a more mature and civilized state, in order to provide a tolerant and accepting environment for patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Do not discriminate against us: we are your compatriots, not your enemies. [Chinese]