After secretly visiting China to mark the 25th anniversary of the 1989 June 4th crackdown last week, Tiananmen protest leader Zhou Fengsuo commented that “the massacre was for this small fraction of families that control China, not for the general well-being of the Chinese. If you look at the people who were hardliners 25 years ago, they are all billionaires now” (via Sunny Yan). At The Diplomat, Sydney University’s Kerry Brown suggests that the interests of the Party’s elite dynasties are more influential now than ever:

As Bloomberg and others have made clear in their tracking of top Chinese families, in the 21st century China seems to be returning to a family-run country rather than a place where individual imperial-style strongmen rule the roost. The family dynamics may well explain why Xi has so vigorously prosecuted his campaign against the grubby money-hungry arriviste Zhou Yongkang, who only has venal business men supporting him. It might also explain the story of the assembly of the Xi clan in 2008 in Beijing where the matriarch, Qi Xin, reportedly berated all the members for being too involved in making money and not focused enough on family honor.

In the family context, obligations are so strong that promises hardly need to be spoken, but they evidently exist. Family honor reigns supreme. Yes, honor involves wealth and power, but it is also something more than that. Seeing China as a place where leaders drum the beat of national greatness while at the same time they are prosecuting campaigns for their clan and tribal interests helps us to make a little more sense of the complexity and ambiguities in the way they speak. Their motivations and promises point in two directions – abstractly to the grand society in which they sit at the top, but more concretely to their own network of interests, the most crucial of which are family ones. [Source]

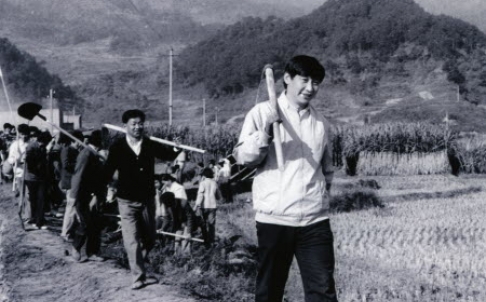

When China marked the 100th birthday of Xi’s father Xi Zhongxun in extravagant style last year, conflicting analyses suggested that Xi was playing the occasion up to emphasize his political authority, and playing it down to avoid being seen as a pampered and privileged princeling. He appears keen to project himself to the public as a down-to-earth man of the people, an image polished by flourishes like a well-publicized bun-shop expedition, but based on his seven years in rural Shaanxi during the Cultural Revolution. He discussed this period in a newly unearthed interview from 2004. From Chris Buckley at The New York Times:

“The first test was the flea test,” said Mr. Xi. “When I first got there, I couldn’t stand the fleas. I don’t know if they still have them. My skin was very allergic to them, and they bit my skin into swathes of red sores that became blisters that burst. It was so painful you didn’t want to live, but after three years my skin was as tough as ox meat and horse hide and wasn’t afraid of being bitten.”

[…] Mr. Xi speaks Mandarin Chinese like a Beijing native. But he said in the interview that he considered himself a native of the region where he was sent down, and that story of being redeemed politically by embracing sacrifice and work among the people remains a part of Mr. Xi’s populist political persona.

“I truly see myself as a Yan’an native,” he said. “Even now, many of the fundamental ideas and basic features that I’ve formed were formed in Yan’an.” [Source]

See more from Zhuang Pinghui at South China Morning Post [Update: and video with transcript at Sina.com, via Chris Buckley]. Other recent moves to burnish Xi’s image include the publication of a book of quotations—including “we cannot use the excuse of reform for our own interests”—and an editorial in an influential Party journal vigorously praising his political vision. From Cary Huang at South China Morning Post last week:

An editorial in the June issue of Qiushi – or “Seek Truth” – said Xi had put forward “new thinking, new views and new conclusions” in a series of important speeches since the 18th National Party Congress in November 2012 addressing the development of the party and the state.

The magazine praised Xi’s speeches as the “latest theoretical achievement in the development of socialism with Chinese characteristics as well as the development of Marxism and Leninism, and Mao Zedong thought”.

[…] “To suggest that his speeches are the theoretical guidelines for the whole party and country is to promote his status to the same level as Mao’s in party history,” said Zhang [Lifan], a party historian formerly with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. [Source]