In part two of our look back at the most notable censored articles of 2023, as selected by CDT’s Chinese editorial team, we present five more articles on such diverse subjects as poverty among older migrant workers, proposed revisions to the “Public Security Administration Punishments Law,” fines and punishments for VPN use, Li Keqiang’s death and political legacy, and the narrowing space for online discourse about the Chinese economy. In part one, we covered five other censored articles about the 2022 “White Paper” protests, ChatGPT, Xi Jinping’s unanimous rubber-stamp re-election, beleaguered stand-up comedians, and censored infographics. (For more on these topics and trending online terminology, see CDT’s newly launched ebook, “China Digital Times Lexicon: 20th Anniversary Edition.”)

The ten articles and essays we have selected represent only a small fraction of the online content that disappears each day from the Chinese internet due to censorship (or sometimes, self-censorship). In 2023, CDT Chinese editors archived and added 287 new posts, essays, and articles to our “404 Deleted Content Archive,” which now contains over 1,515 items in total.

6. “Migrant Workers in Their Elder Years,” by Qiu Fengxian

On July 5, a video lecture on the subject of elderly migrant workers by Qiu Fengxian, an associate professor at Anhui Normal University who researches the migrant workforce, attracted widespread attention. After conducting a study in which she sent out 2,500 questionnaires and interviewed 200 migrant workers, Qiu concluded that China’s first generation of migrant laborers, after spending nearly three decades working in large cities, had become a “forgotten generation”: afflicted by ailments, excluded from the social services net of large cities, short of savings, and unable to afford to retire.

The video originally appeared as a TED Talk-style video for Yixi (一席, Yīxí), a platform featuring educational lectures. (Yixi has a WeChat public account as well as a YouTube channel.) Later, when the WeChat public account 正面连接 (Zhèngmiàn Liánjiē, “Positive Connection”) published highlights of Qiu’s survey under the title “Three Decades of Working Like This,” it was promptly deleted, and video and text versions of Qiu’s Yixi lecture were also taken down (The full lecture has been archived here, on CDT’s Chinese-language YouTube Channel). The censorship has continued into 2024: just one day after the release of a NetEase News documentary about migrant workers (also titled “Three Decades of Working Like This”), it was taken offline, and a hashtag of the documentary’s title was blocked on Weibo. But this repeated censorship cannot completely suppress important questions about the treatment of the generation of migrant workers who built the Chinese cities we see today. As Qiu Fengxian noted in her lecture, “The first generation of migrant workers labored in these cities all their lives, just like urban residents, but they ended up with nothing. This is not normal.” One internet user, commenting on the censorship of the NetEase News documentary, lamented, “So if you go out and make a film about the real lives of the underclass, apparently it has to be banned in China because it deviates from the “main melody.”

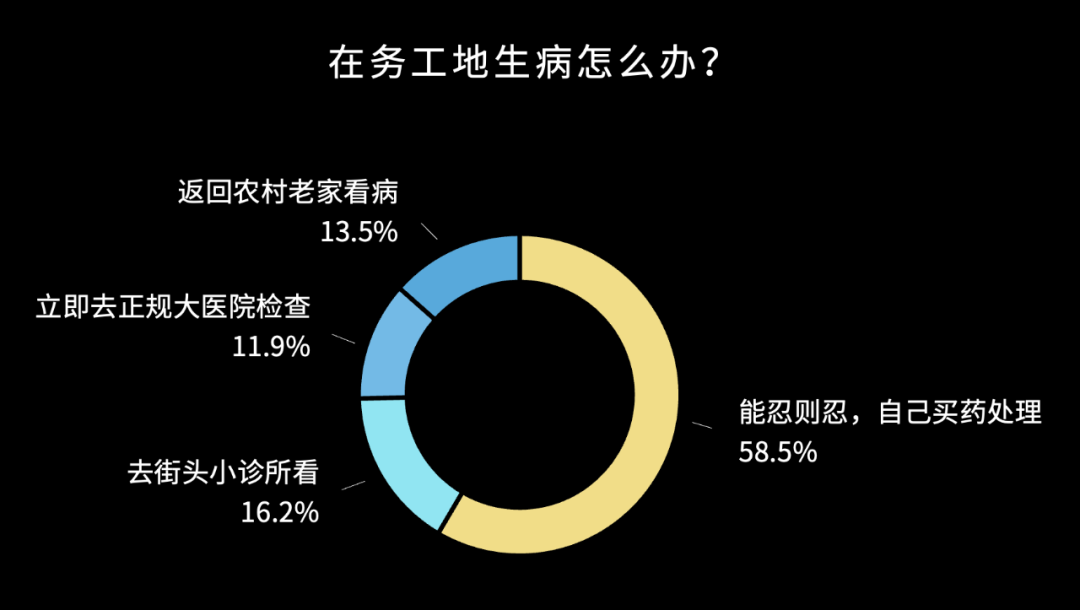

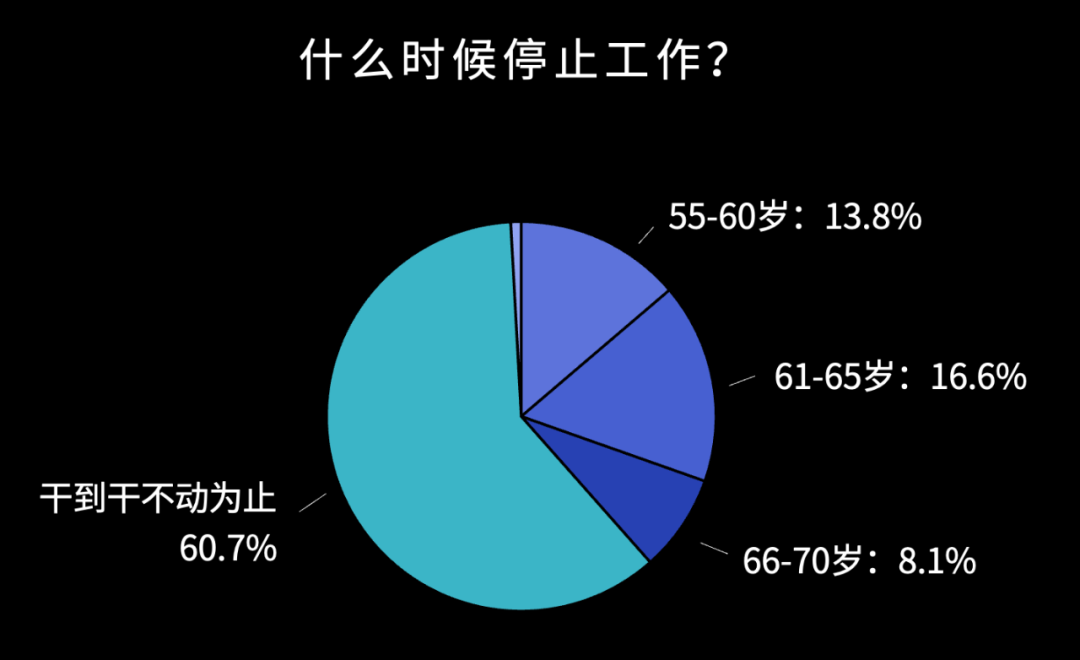

Below are some of the infographics featured in Qiu’s lecture. They make for sobering reading. Qiu found that 58.5% of migrant workers do not seek professional medical help for illness, and that 60.7% have no plans to retire and will work until they are physically unable to continue:

What do you do if you fall ill at your work site?

Survey responses, included in the circular graph:

Bear it, buy my own medicine: 58.5%

Return to my village to see a doctor: 13.5%

Go to a major hospital for an evaluation: 11.9%

Go to a street-side clinic for a check-up: 16.2%

When do you plan to stop working?

Survey answers, included in the pie chart:

I will work until I am physically unable to: 60.7%

Ages 55-60: 13.8%

Ages 61-65: 16.6%

Ages 66-70: 8.1%

7. “Media Silence on the ‘Public Security Administration Punishments Law’ is Deafening,” by Wei Chunliang

Early September saw the censorship of current-affairs blogger Wei Chunliang’s article about the deafening media silence on proposed amendments to the “Public Security Administration Punishments Law.” The amendments, which were at the time open for public comment, proposed “criminali[zing] comments, clothing or symbols that ‘undermine the spirit’ or ‘harm the feelings’” of the Chinese nation. Wei noted that while many legal experts had expressed alarm that the proposed amendments were overly broad and could be applied arbitrarily, Chinese media outlets were almost uniformly silent on the matter. Wei’s censored post contained a long list of major Chinese media outlets that had zero coverage of proposed changes to the law, and mentioned a number of legal scholars who had bravely commented on the problematic proposals. The media silence, Wei wrote, was yet more proof that “over time, our traditional media outlets have lost their ability to write about and influence issues that actually matter.” He ended his post by including links to sites where citizens could comment on the proposed amendments, and urged his readers to weigh in with their opinions.

8. “I Was Fined a Million Yuan by the Police for Circumventing the Great Firewall to Access the Open Internet for Work,” by a computer programmer in Chengde, Hebei

In September, a Weibo user working as a computer programmer in Chengde, Hebei province, reported that he was fined and had three years of income confiscated by the local public security bureau for using a virtual private network (VPN) to circumvent the Great Firewall (GFW) while working for an overseas client. Supporting documentation provided by the programmer on Weibo showed that the Shuangqiao Branch of the Chengde public security bureau (PSB) levied a 200 yuan ($27 U.S. dollar) fine and confiscated three years of the man’s earnings, totaling 1.058 million yuan (over $144,000), for the period 2019-2022. The programmer’s post, which was partially translated by CDT, was later censored:

Thank you, online friends, for your support and concern.

[…] In April and July of this year, I was interviewed by the police several times, during which I explained my employment situation in detail and provided [them with] my bank card, my employer’s company registration information from the country in which it is located, the consulting contract I signed with the company, and other supporting documents. During this period, the PSB informed me that their investigation concluded I had nothing to do with the Twitter incident, but that I would be penalized for circumventing the GFW, and that my income would be deemed “illegally obtained income.”

In August of this year, a formal administrative penalty verdict was issued: circumventing the firewall is illegal, thus any income earned from “scaling the wall” is considered illegally obtained income.

On September 5 of this year, I applied for administrative reconsideration, but the department in charge of reconsideration essentially concurred with the opinion of the PSB. If I wish to proceed, I will need to file an administrative appeal through the courts.

Throughout this process, I have stated many times that both github.com and my employer’s after-sales service and support website can be accessed without circumventing the GFW, and code can be written on a local computer without circumventing the GFW, but these explanations were not accepted.

The next step is to retain a lawyer to actively prepare for my administrative appeal in the courts. [Chinese]

News of earnings from work done outside the Great Firewall being classified as “illegally obtained income” had a chilling effect on Chinese professionals who use VPNs to access the global Internet for work. Since a 2017 crackdown on VPNs and the introduction of new rules regulating their use, numerous VPN apps have disappeared from Chinese app stores; many Chinese domestic VPN providers have been fined, driven out of business, or even imprisoned; state-run telecom providers have been ordered to block customers’ access to VPNs; Chinese Twitter users have been tracked down and punished; and academic, scientific, and business communities have been hit hard by lack of access to essential online source material. VPN regulation enforcement and punishment can vary widely, ranging from minor fines and naming and shaming to long prison sentences.

Shuai Li, writing at Medium, delved into the identity of the programmer, his employer, and his prolific work on Github. The programmer’s plight, in addition to generating some discussion on Reddit and other tech-related sites, fueled a groundswell of criticism on Chinese social media, with some commenters criticizing Chengde for imposing excessive fines, and others joking about steering clear of Chengde, lest they have their wages garnished for VPN infractions.

9. “Li Keqiang’s Backstory,” from WeChat account 喀秋莎来信 (Kāqiūshā Láixìn, “Letter from Katyusha”

After former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang passed away on October 27 of a sudden heart attack at the age of 68, there was a surge in online censorship about his life, death, and legacy. Li Keqiang was largely overshadowed by Xi Jinping during his lifetime, and was eventually pushed to the sidelines politically, but for many Chinese citizens, his death was seen as a symbol of an alternative path for China, thus imbuing any tributes to the former premier with a heightened political sensitivity. CDT translated a censorship directive that instructed media outlets to only quote copy from mainstream central media outlets (such as Xinhua, CCTV, and People’s Daily), to exert control over comments sections, and to beware of “overly effusive comments and assessments” about Li’s political and historical legacy. Numerous tributes to Li were censored online, including the photo essay mentioned above, which although not overly glowing, featured a plethora of images from throughout the course of Li’s personal and political life. Despite the stringent censorship, many Chinese citizens still mourned Li on social media, with some posting tributes to Li Wenliang’s Wailing Wall. “Today, it seems another truth-teller with the surname Li has departed,” wrote one Wailing Wall visitor. Others complained that even expressions of grief were being censored, and noted that the comments sections under some online news reports of Li’s death had been shut down.

In early January, Caixin Weekly’s “Year in Memoriam” feature about prominent figures who died in 2023 was mysteriously deleted soon after publication. Li Keqiang was one of the individuals featured in the article, along with doctors Jiang Yanyong and Gao Yaojie, famed jurist Jiang Ping, and thallium poisoning victim Zhu Ling.

10. “China’s Socio-economic Contradictions Are Nearing a Critical Point,” belatedly censored 2012 Caijing interview with economist Wu Jinglian

In the latter half of 2023, there was a marked increase in online censorship of economic content, particularly of studies or articles analyzing the underlying causes of China’s current sluggish economic growth. Each month saw the deletion of articles about high youth unemployment, slowing economic growth, the troubled property sector, economic inequality, economic reform, and other pressing economic topics.

One such article was “Ten Questions About the Private Economy”—published and later deleted from the WeChat account “Caijing 11”—in which four prominent Chinese economists (Huang Qifan, Liu Shijin, Shi Jinchuan, and Zhang Jun) discussed a number of economic and structural issues with journalists from the finance magazine Caijing. Economist Liu Jipeng, dean of the Capital Finance Research Institute at China University of Political Science and Law, seemed to have been banned or otherwise restricted on several social media platforms, likely in retaliation for some of his recent comments on the moribund Chinese stock market. Users on Douyin, Toutiao, and Weibo reported that Liu’s accounts were not permitting new followers. In early December, Liu gave a keynote speech at a finance conference in which he criticized stalled reforms in China’s capital markets. Noting that China has had 45 years to enact “reform and opening” policies and 33 years to develop its capital markets, he said that this is still “a market with an unfair distribution of wealth and a lack of justice.” One Weibo commenter wrote that “Liu Jipeng being banned is an example of their tried-and-true method: if [the government] can’t solve the problem, it will punish the person who brought the problem up for discussion.”

In an example of extremely belated censorship, a September 2012 Caijing magazine interview with famed economist Wu Jinglian was deleted from WeChat in early December, 2023. The extensive interview, which experienced a resurgence in popularity after it was shared by WeChat finance and economics blogger Leng Xiao, discussed the need to curtail state interference in the economy, continue market-based economic reforms, and strengthen the rule of law. The now 93-year-old Wu Jinglian was—and perhaps still is—one of China’s most recognizable and widely respected economists, known for his frank pronouncements and incisive analysis. A 2003 editorial in the Wall Street Journal opined, “If there’s one economist in China always worth listening to, it’s Wu Jinglian,” and described him as a “master diagnostician.” Two months before the Caijing magazine interview, in a keynote speech at a global conference sponsored by the International Economic Association, Wu Jinglian had declared, “China still lacks a legal foundation that is indispensable for a modern market economy. Government officials intervene in the market at their will through administrative means.” Eleven years later, it seems that Wu’s critiques are still relevant enough to alarm China’s censors.