The ten censored essays collected below are a first draft of an unauthorized history of the extraordinary year 2022, compiled by CDT Chinese editors. Toward the end of the year, discontent over the zero-COVID policy burgeoned into contention over the Party’s right to rule. In 2015, the journalist Jiang Xue, whose essay “Ten Days in Chang’an” heads the list below, told an interviewer, “I’m not a particularly brave person, but I can weigh my choices and decide what cost I’m willing to bear for the sake of freedom and independent expression.” This past year, tens of thousands across China joined Jiang Xue in “weighing their choices” and decided to risk grave danger to voice their opinions. Censorship was but the first punishment many of the authors below were willing to endure as the price of speaking up. Arranged together, the essays are modest rather than incendiary, still less revolutionary: a pandemic diary, a compilation of visual art, a list of those who died during Shanghai’s lockdown, an archive of 33 attempts to disguise a censored video, a report on a bank depositor, a poem about cicadas, a policy proposal, a cri de coeur, a list of 10 questions, and a photo essay of a vigil. None passed censors’ muster. These essays are not the “most censored” essays of the year, but rather a selection of notable pieces that were scrubbed from the web. A selection of each has been excerpted and translated into English below.

1. “Ten Days in Chang’an”

The Xi’an lockdown, which began in late 2021 and continued into January of 2022, was among the first such measures across a major city since Wuhan in 2020. Xi’an residents, prevented from leaving their apartments to buy groceries, went hungry as the government blithely praised various food-aid campaigns by comparing starving residents to noodles. Unable to purchase foodstuffs in person, people turned to e-commerce sites which, unprepared for the sudden spike in demand, were either out of stock or charged exorbitant prices. Dark jokes compared Xi’an residents trying to shop online to eunuchs in a brothel—“they can look all they want, but they can’t buy.” Some of the city’s leading cultural lights, notably famed author Jia Pingwa, put out anodyne calls to “extinguish our fear” and “vanquish this pandemic.” Others, like the former pathbreaking journalist Jiang Xue, set out to uncover the truth. Her reportage on the lockdown, “Ten Days in Chang’an,” mined the same literary vein as Fang Fang’s “Wuhan Diary.” Jiang rejected the “victory at any cost” mindset trumpeted by officials in favor of a specific focus on the lives and deaths of individuals. Her essay was soon censored. In the excerpt translated below, Jiang responds to a former friend of hers, who was praising “societal clearance,” a then-new euphemism for the lockdown, and demands that attention be paid to those who bore the brunt of Xi’an’s suffering. Jiang Xue’s “Ten Days in Chang’an”:

“‘Xi’an cannot but be victorious,’ is but a boast, a platitude, an empty phrase. Similar phrases include, ‘We must win at any cost.’ The phrase seems fine, but in its concrete application, we must consider: are ordinary people like us the we, or the cost that must be paid?

“After this is all over, if we do not reflect on and internalize the lessons we’ve learned through blood and tears, but rather busy ourselves handing out awards and singing odes, then the people will have suffered in vain.”

I do not plan to see him again. Yet I do wish to tell him that no matter what grand narrative emerges to describe this city’s suffering, tonight I am only concerned for the young woman who lost her father, and the woman who tearfully begged an anonymous pandemic prevention worker for feminine products, and the young mother who spoke repeatedly of her plight, and also for everyone who has been humiliated, or hurt, or overlooked. There was no need for them to suffer like this.

I also want to tell him that in this world, no man is an island—the death of any one is the death of us all. The virus hasn’t claimed any lives yet here in Xi’an, but lives have been lost due to other causes, that much seems probable. [Chinese]

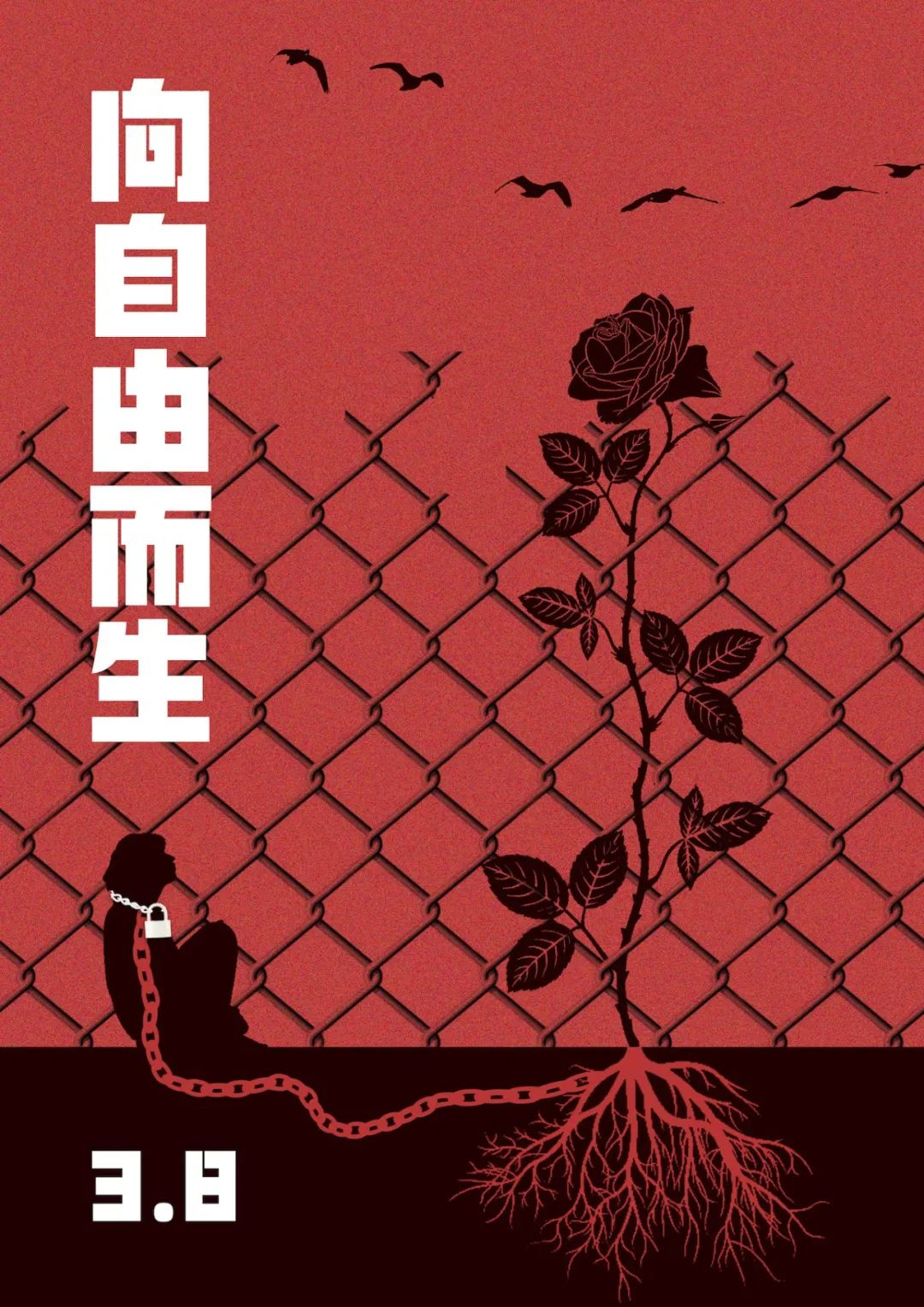

2. “International Women’s Day Posters, Artwork, and Banners” and English translations: Parts (1), (2), and (3)

In January, a shocking video of a shackled woman in Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province began circulating on Chinese social media. After initial attempts to sweep the issue under the rug only spurred greater anger, Chinese authorities published a number of conflicting statements that nevertheless gave the outline of the woman’s life. Her name was Xiaohuamei, and she had been trafficked, twice, and sold as a “wife” to a man named Dong Zhimin, by whom she bore eight children. Citizen journalists and online sleuths were instrumental in uncovering more information about her life. The posters translated below, collected from across the Chinese internet in a now-censored essay, were published in honor of International Women’s Day. They are testaments to China’s feminist movement and the intersectional relationship between feminism, censorship, state power, and freedom:

“Born to be free” [English]

Blue cover with white Xinhua News font characters: “Official Press Release”

Image beneath the cover: Xiaohuamei’s face from the Tianjin mural that was painted over, composed of the Chinese characters for “freedom.” [English]

Red banner: “Who left their book of fairytales open? Because someone let the princess out. —All the boys”

White sign: “Who left their book of fairytales open? Because someone’s keeping the mother locked up in chains.”

“Girl Helps Girl” [The smaller text is unclear, but the word “trafficking/trafficked” is visible.] [English]

3. “Shanghai’s Deceased”

In April, Shanghai went into lockdown. In a repeat of the experiences of Wuhan, Xi’an, Urumqi, and countless smaller towns, the lockdown caused major delays in normal non-COVID medical care, leading to many seemingly preventable deaths. One WeChat essayist set out to chronicle a small portion of those deaths, organized by date. The list reveals that the breakdown in normal medical services turned often-treatable conditions such as asthma, depression, and fever into death sentences:

March 30: An asthma patient in Pudong

A timeline published by the patient’s daughter:

8:00 a.m. Her father faints after suffering an asthma attack. Two doctors conducting COVID tests nearby arrive on the scene, begin performing CPR, and instruct the family to call for a defibrillator.

8:45 a.m. An ambulance arrives at their building, but it was called for a neighbor. Requests for a defibrillator are unsuccessful.

The daughter and other neighbors repeatedly inquire whether they can take the father to the hospital in a private car or police vehicle. The neighborhood lockdown makes these efforts impossible.

9:18 a.m. The local police station sends over a defibrillator.

9:29 a.m. A second ambulance arrives.

10:00 a.m. EMTs carry an empty stretcher out of the building. The elderly man has died.

[…] April 11: A young woman with depression

[After she cannot refill her prescription] due to medicine shortages, her depression worsens; unable to obtain timely medical treatment, she commits suicide by jumping from a building.

A top executive at a securities firm

On April 12, there are news reports that Wei Guiguo [a vice-president at Netcom Securities] passed away at home from a cerebral hemorrhage after efforts to call for medical help were unsuccessful due to the lockdown.

An elderly woman

An elderly woman has a high fever and is unconscious. Her COVID test is negative. An ambulance arrives, but EMTs say the local fever clinic is closed. With no way to lower the woman’s fever at home, she passes away without regaining consciousness. [Chinese]

4. “Archiving 33 Versions of The People’s Art”

In late April, the remarkable audiovisual essay “Voices of April,” which documented both the suffering of Shanghai residents under lockdown and their acts of resistance, went viral on WeChat. It became the immediate target of an all-out censorship effort. Two leaked censorship directives, likely from the Beijing and Guangdong Cyberspace Administrations, instructed social media platforms to “perform comprehensive clean-up of video, screenshots, and other content related to ‘Voices of April,’” and noted that “all videos related to or involving ‘Voices of April’ are barred from being posted or reposted, without exception.” In turn, netizens launched a spontaneous collective anti-censorship effort that attempted to disguise the video within various other forms of media. It was an outpouring reminiscent of the 2020 attempt to preserve a censored interview with the Wuhan doctor Ai Fen by replacing certain Chinese characters with complex homophones, translating the interview into Elvish and Klingon, and other creative efforts. This essay, “Archiving 33 Versions of The People’s Art,” is a compilation of some of the more creative and popular attempts to disguise the “Voices of April” video. The compilation itself was later censored:

Hidden within a photograph of China’s Civil Code

Prefaced with a warning that often appears after content has been censored: “This content is temporarily unable to be viewed.”

Framed within a still from the cartoon “SpongeBob SquarePants”

Framed by four negative COVID test.

Disguised beneath a superimposed Chinese flag and a list of the “12 Core Socialist Values.” [Chinese]

5.“All Who Offend Us Will Be ‘Red-Coded,’ No Matter How Far Away They Are”

In March, thousands of depositors across four Henan village banks found their deposits frozen after a major shareholder’s “serious financial crimes” threatened the banks with insolvency—a not altogether uncommon occurrence at the rickety institutions tasked with providing financing to rural economies. What happened next was extraordinary: depositors who traveled to Henan to demand the return of their funds found that their health codes had mysteriously turned red. It turns out that government officials had colluded with the banks to identify potential protestors and bar them from traveling within the province—a blatant abuse of a public-health measure designed to prevent uncontrolled COVID outbreaks. (Depositors who did manage to protest in Zhengzhou, the provincial capital, were assaulted by anonymous assailants, likely thugs-for-hire deployed by the local government.) The title of this essay, “All Who Offend Us Will Be ‘Red-Coded,’ No Matter How Far Away They Are,” is a play on the tagline—promising revenge against all perceived enemies of China—from the nationalistic film “Wolf Warrior II.”. The essay documents the experiences of depositors given red codes and stonewalled by the smiling face of a bureaucracy intent on keeping them from protesting:

Yesterday, not long after Miss Ai checked into a hotel in Zhengzhou, a middle-aged policeman and a pandemic prevention worker knocked on her door and took down her information, after which they inquired in a friendly manner:

“What’re you doing in Zhengzhou?”

Miss Ai told the truth: she had come to withdraw her money. Not long after, upon stepping out for food, Miss Ai discovered that her health code had turned red.

[…] In the end, pandemic prevention personnel registered Miss Ai with “the relevant department” and then sent her to a quarantine hotel in the distant hills.

During the whole process, the only person to give Miss Ai even the barest of “explanations” was a regulator who said:

“We’ll turn your code green, just go home and wait for more information.” [Chinese]

6. “Address To The Cicada”

It was perhaps a simple diatribe against cacophonous insects, but censors took no chances with journalist Xuan Kejiong’s poem about cicadas. Netizens certainly did not think it was a simple poem impugning the intelligence or rhetorical predictability of the bug: the poem was widely perceived as a dig at Xi Jinping. Xuan was once arguably Shanghai’s most famous journalist, widely respected for his tireless coverage of disastrous happenings in the city. After publishing this poem to his personal Weibo account, Xuan’s account was suspended, and some online reports suggested that he was subject to formal censure within Shanghai Media Group, the state-run media group where he is employed. If the poem was a disguised barb aimed at Xi, Xuan was not alone in his displeasure with China’s top leader. The poem, originally a Weibo post, has been translated in full:

Shut up!

Yeah, I’m talking to you

Up in the high branches

Making a racket

Adding to the heatYou think you’re so clever

Plump and well-fedLying dormant

Underground

Crawling out of the darkness

Every five years

Only able to use its ass

To sing hymns to the dog days of summer

Ignorant of the blistering hardships of humanity#Address to the Cicada# [Chinese]

7. “It’s Time for China to Change its Pandemic Control Policy”

This essay’s censorship is a pertinent reminder that essays can be erased not because they are antagonistic to the state, but rather are too anticipatory of it. This essay, published in August by ANBOUND, an independent international think tank, called for the end of China’s zero-COVID policy three months before the state moved to end it. While the state’s rationale for ending the policy remains opaque, it is likely that economic considerations were paramount, which was the exact suggestion made by ANBOUND (although the think tank’s suggestion of gradual reintegration was much more sensible than the abrupt U-turn that ultimately occurred.) The essay went viral within China before it was censored:

Final Analysis, Conclusion:

Now that the pathogenic risk of the coronavirus has decreased dramatically, preventing economic stagnation should be the primary domestic policy objective. If China wishes to maximize benefit and minimize harm in this complex international and regional geopolitical and economic landscape, it must scientifically adjust its pandemic prevention policy in light of the latest pandemic developments. With economic recovery as a priority, China must slowly reintegrate with the world during this period of normalized pandemic prevention and control mechanisms. [Chinese]

8. “What Makes You Think It Couldn’t Have Been You on that Early-Morning Bus?”

In September, 27 people were killed after a bus transferring them to a remote quarantine facility in Guizhou Province crashed at 2:40 a.m. All 27 were “close contacts” of people infected with COVID—not diagnosed coronavirus patients—being removed from the city limits of the provincial capital Guiyang in order to achieve “societal clearance” by city officials’ self-imposed deadline. The bus immediately became a resonant symbol of the tragic folly of zero-COVID policy, and a broader metaphor for China’s political trajectory. This censored essay, originally posted to WeChat, asked readers, “What Makes You Think It Couldn’t Have Been You on that Early-Morning Bus?”:

In an instant, a grain of the sands of time can become a hammer delivering a fatal blow, sending you into the abyss.

Who’s to say we weren’t on that early-morning bus? We’re clearly all on it. Can’t you see?

Isn’t that the reason we feel so anxious taking our daily COVID tests? Because we’re afraid of getting on that bus?

The past few days, netizens have been debating whether or not high-speed trains should sell toilet paper.

I can’t help but find it all funny.

Do we have any power over what the railroad bosses choose to sell?

You and I don’t even have the power to refuse to board that early-morning quarantine bus.

The bus has infinite capacity.

In truth, we’re all on the same bus. It’s just that we didn’t happen to be on the one that overturned on the hillside. At least, not yet. [Chinese]

9. “Ten Questions” Not to Ask About Pandemic Policy

This list of “Ten Questions” went hugely viral upon its publication to WeChat in November. Censors soon stepped in to delete it, and permanently banned the account behind it. “We don’t solve problems. We ‘solve’ the people who ask about them,” quipped a netizen afterwards. As opposed to the above essay, “It’s Time for China to Change its Pandemic Control Policy,” which offered prescriptive advice to the state, this essay asked pointed questions that exposed the increasing irrationality of China’s “zero-COVID” policy. After the essay was censored, a similarly viral follow-up essay, “The Eleventh Question,” asked: “What gives you the right to delete ‘Ten Questions?’” The following excerpt is from “Ten Questions”:

Question One: Is the main responsibility of the National Health Commission to compile data related to COVID-19? How much public outreach work has the National Health Commission done regarding medical treatment for COVID-19 patients? Has the National Health Commission made public the fatality rate of the Omicron variant? How many people has the National Health Commission punished for implementing excessive pandemic prevention measures at the grassroots level? Does the National Health Commission think that this year’s extended, months-long lockdowns in Xinjiang, Tibet, and other areas are appropriate?

[…] Question Five: When it comes to managing COVID-19, what are our benchmarks for lifting restrictions? If there are no objective, scientific benchmarks, does that mean that the restrictions will simply continue?

[…] Question Nine: More than 120 countries worldwide have long since lifted COVID-related restrictions or controls. Has public health in these countries been harmed? Are their people living normal lives? Why can they live more freely than Chinese people? The World Cup just kicked off in Qatar. None of the fans were wearing masks, and no one was asked to show a nucleic acid test certificate. Are we even living on the same planet as them? Can COVID-19 not harm them? [Source]

10. Urumqi Road, 11/26/2022

In late November, extraordinary anti-lockdown (and, in some cases, anti-regime) protests broke out in cities across China after at least 10 people died in a fire in a locked-down Urumqi apartment complex. Censors immediately moved to quash all mention of the protests. Security forces also began a stealthy campaign to identify and arrest participants. This visual essay documented one of the more extraordinary gatherings at Shanghai’s Urumqi Road—a quiet vigil for the deceased that escalated, among some of the mourners, into an explicit call for Xi Jinping to step down. Perhaps the most striking image in the visual essay was a photograph of a young woman wearing a surgical mask with “404” written across the front, internet slang for censorship and the inspiration for CDT’s “404 Archives”:

[Chinese]