As China’s Lunar New Year holiday continues throughout this week, CDT Chinese editors have collected and republished over a dozen essays, articles, and other content reflecting the zeitgeist of the transition from 2023’s Year of the Rabbit to 2024’s Year of the Dragon. As blogger Xiang Dongliang noted, this year’s holiday was notable for fewer red envelopes—but more advertisements on CCTV’s annual televised Lunar New Year’s Gala. It was also notable for the sheer number of people traveling (610 million train tickets were sold in the two weeks before Lunar New Year) and disruptions due to heavy snowstorms and blizzards in many cities and provinces of central and eastern China, including Chongqing, Guizhou, Hubei and Anhui.

The Lunar New Year’s content archived here can be divided into several broad categories: hometowns and family life, winter weather, the challenges that lie ahead, and language and culture.

Hometowns and Family Life

A question posted to the Q&A site Zhihu (“Why do so many families fight during Lunar New Year?”) drew numerous detailed responses, some of them quite dark, covering the gamut of family dysfunction, mental health issues, strictures of tradition and patriarchy, and parental pressure to marry, reproduce, or earn more money. Zhihu user WDKYMYS answered that they hate going home for Chinese New Year because of their parents’ dysfunctional marriage and constant bickering, and confided that they often wished their parents would just get a divorce and be done with it. Another Zhihu user, writing anonymously, observed that younger people living in the city tend to put up a false front and revert to ossified gender roles when visiting parents or in-laws in the countryside, which can lead to arguments. Respondent 笑百步 (xiàobǎibù) listed four factors fueling familial conflict during the New Year: increased financial burdens, tight quarters shared with relatives, status competitions, and loss of faith in the future.

An article from Weibo account 书生意气看世界 (shūshēng yìqì kàn shìjiè, “looking at the world from a scholarly temperament”) notes that for many middle-aged workers, this Lunar New Year is a time of anxiety due to the widespread problem of unpaid wages. But for younger people returning to their hometowns at New Year, writes the author, the main source of anxiety is familial pressure to settle down, get married, or have children. Many find themselves fending off parental pressure to get set up on dates, go on blind dates, or accept the services of a matchmaker; some would rather avoid this by not going home at all.

WeChat account 3号厅检票员工 (sānhàotīng jiǎnpiào yuángōng, “the ticket-taker in theater three”), which covers current events from a cinephile’s perspective, wrote a New Year’s essay about the invisible sacrifices and contributions of women. Per the account’s focus on film, the author dissects two female cinematic characters whose unwavering support of the male protagonist is overlooked and ignored: Qin Cairong from the quirky 2021 sci-fi film “Journey to the West” (Chinese title:《宇宙探索编辑部》Yuzhou tansuo bianjibu) and Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer from the 2023 biopic “Oppenheimer.” The author also mentions the films “Barbie” and “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” as well as “Tell Me, Mom—Why Would I Bother to Get Married?,” a spoken-word video that has been viewed over one million times on Bilibili. Addressing her mother, the video’s narrator says, “Dad loves Lunar New Year, but I know you hate it, Mom, because while he and his friends are eating and drinking and talking big, basking in familial warmth and affection, you’re slaving in the kitchen alone. And after all the dishes have been eaten, after all the friends have left, you’ve got more work to do, picking their garbage up off the floor and cleaning up their mess.”

Winter Weather

For many traveling home for Lunar New Year, the joy of family reunion was tempered by travel delays and disruptions due to intense snow and rainstorms in many areas of the country. A Sanlian Lifeweek Magazine feature described some of the nightmare travel scenarios: fliers stranded at Wuhan’s Tianhe Airport for 30 hours; drivers navigating icy roads, sleeping by the roadside, or caught up in a six-mile-long traffic jam on the Shanghai-to-Chengdu section of Wuhan’s Outer Ring Expressway; and a family trapped in their car for 18 hours on the final 50 miles of their journey home to Hubei. The Beijing News WeChat account focused on human interest stories published a similar feature, with photographs of traffic jams, trees and plants covered in ice, people pushing vehicles through snow, and vendors selling noodles and other snacks to stranded motorists.

On February 4, 2024, heavy rain and snow caused a six-mile long traffic traffic jam on the Shanghai-Chengdu section of the Wuhan Outer Ring Expressway in Hubei Province. (source: Sanlian Lifeweek/Visual China Group)

Pushing a cart through heavy snow (source: interviewee/Beijing News/WeChat)

Upon arriving home after a long journey, a weary traveler drew a smiley face in the snow. (source: interviewee/Beijing News/WeChat)

In Hubei, where as many as hundreds of thousands of people were stranded on ice- and snow-covered expressways, the local government’s anemic response to the weather was widely criticized. It was only after a massive public outcry and mockery on social media that local officials finally sent crews to remove ice and snow from motorways and allow traffic to flow freely. As one online commenter joked, “While the surrounding provinces are clearing snow and ice, Hubei is busy educating people about natural disasters.”

The unusually harsh weather has inspired some wild conspiracy theories about this year’s ice- and snow storms being “climate weapons” (气象武器, qìxiàng wǔqì) deployed against China by its enemies. In her Lunar New Year’s post, WeChat blogger Princess Minmin deplored the anti-intellectual currents fueling such unfounded conspiracy theories, and urged her readers to keep their wits about them and not succumb to stupidity or fear.

The Challenges Ahead

In their Lunar New Year’s posts, many online writers focused on the challenges—social, economic, political, or spiritual—facing China in the year ahead.

While some workers were worrying about their unpaid wages, others were denied time off during this year’s holiday. An article from WeChat account 温州家长 (Wēnzhōu jiāzhǎng, Wenzhou parent/s) decried the meaningless formalism of forcing already beleaguered teachers to work during Chinese New Year, when classes are not in session. Teachers are often assigned to “guard” empty school campuses, despite the fact that many of these campuses have security guards and turn off the heat and water during school vacations. Some teachers who complained about having to work during the holiday were ridiculed online, and a reporter who called one school district to inquire about the practice was told that there was “no mandatory requirement” that teachers stay on duty during the holiday—a claim that was met with incredulity by teachers forced to give up their Lunar New Year holiday. (For more on overworked teachers, see previous CDT posts on teachers forced to work as online “positive energy” commentators, or as “bit players” to bolster numbers and police the conduct of others during inspection visits by high-level cadres.)

Writer and political commentator Ye Kefei highlighted socio-political challenges in a Lunar New Year’s letter urging friends and readers to “stay alert and stay angry”:

Since ancient times, Chinese society has faced a problem: there is much more talk about society than about the individual. Individual feelings are always subservient to the feelings of society or the feelings of those in power. There is a limited vocabulary for expressing genuine personal emotions or pain, and the channels for this kind of expression are even more limited. This gives rise to enormous inhibition, thus prohibiting normal expressions of human nature and emotion.

[…] For the individual, hypocritical “positive energy” is meaningless. Staying alert at all times, assessing the future, staying angry at all times, and making demands of both yourself and society—these are the only ways to save yourself.

I hope that all my friends will stay alert and angry, and will take action, instead of just talking. [Chinese]

WeChat blogger Wei Chunliang published a post acknowledging that the last year had been a difficult one, and affirming the Chinese people’s right to fireworks, freedom, dignity, and normality:

People setting off fireworks and watching fireworks (regardless of whether or not they’ve been given official permission to do so) isn’t just about having fun, but about the fundamental right to live a normal life. It represents a tiny victory in the fight for the right to control our own lives.

If you read the news at all, you will be aware that there are too many things we are “forbidden” to do: we are forbidden from burning coal, or forgetting to fold our quilts, or posting advertisements in front of stores, and on and on and on. These “forbidden” activities are all backed up by fine-sounding logic, and we have become habitually docile.

Having accepted so much else, the Chinese people who have worked hard all year ought to have the right to watch fireworks. If you’re not fond of fireworks, feel free to replace that word with anything else you enjoy. This is about more than fireworks, more than Chinese New Year. In sum, all of us deserve to be allowed to live normal lives in a normal society in a normal age. [Chinese]

The people deserve fireworks (image: Wei Chunliang/WeChat)

Many online essayists, bloggers, and citizen journalists have found it increasingly difficult to write about topics of their choosing without having their social media accounts suspended, banned, or attacked in a polarized era. Prolific Wechat blogger 海边的西塞罗 (hǎibiān de Xīsāiluó, “Cicero by the sea”) addresses this in a Lunar New Year’s message of gratitude to readers:

Despite my best efforts, I feel like societal opinion is (very visibly and rapidly) becoming more polarized. Nearly every news item seems to inspire only two uncompromising responses—either fanatical support or vitriolic hatred. In catering to these two types of voices (and perhaps this is due to the popularity of short-form video as a vehicle for expressing such uncompromising emotions), self-published media discourse may also become divided into two factions, with nary any middle ground, or room for compromise or reconciliation.

[…] I think these are the reasons why I persist in doing this, why I continue to write. For us ordinary people, our present tranquil lives are dependent on the tranquility, tolerance, and rationality of society as a whole. To safeguard these, I will continue to write, taking it day by day. If one person understands, that means I have won over one person. I will continue to do this to the best of my ability, until death do us part.

I am also grateful to all those friends who understand me. I am but a mere mortal, a fragile being. Those times I have been in danger, I thank you for lifting me up. [Chinese]

Language and Culture

Lastly, some of CDT’s archived Lunar New Year content revolves around language and culture. One post dissects the trend of using rare, archaic, variant Chinese characters in Lunar New Year’s greetings, while another delves into the recent controversy over Chinese dragons vs. Western dragons, and whether the standard English translation for this year’s Chinese Zodiac animal should be the familiar “dragon” or the unfamiliar “loong.”

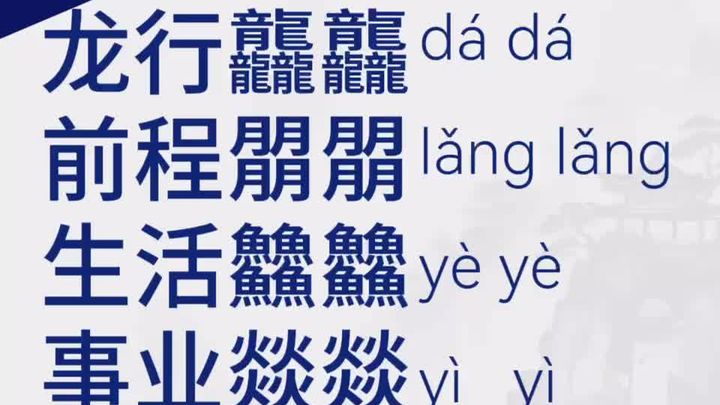

The WeChat account 读宋史的赵大胖 (dú Sòngshǐ de Zhào dàpàng, “Fatty Zhao, student of Song Dynasty history”) takes aim at this year’s online trend of using complex variant characters for Lunar New Year’s greetings. The author explains the meaning, pronunciation, and derivation of some of these complex and repetitive characters, but concludes that he dislikes the trend. The goal of language is to communicate with clarity, he writes, not to show off one’s knowledge or leave the reader baffled.

The Chinese text of the message above reads:

龙行龘龘 lóng xíng dá dá

前程朤朤 qiánchéng lǎng lǎng

生活䲜䲜 shēnghuó yè yè

事业燚燚 shìyè yì yì

An approximate translation of the greeting is:

May the dragon soar—

Wishing you a bright future,

an abundant life,

and a blazingly successful career!

The final two characters in each line are formed by repeating the same radical three or four times. In the first line, the character 龘 (pronounced dá, and meaning “the appearance of a dragon in flight”) is formed by repeating the traditional-form character for “dragon” (龍, lóng) three times. In the second line, the character 朤 (lǎng, meaning “bright future”) is formed by four repetitions of the character 月 (yuè, “moon” or “month”). In the third line, the character 䲜 (yè, “many fish”) is formed by repeating the character 鱼 (yú, “fish”) four times. And in the fourth line, the character 燚 (yì, “a fire burning fiercely”) is formed by four repetitions of the character for “fire” (火, huǒ).

The Propaganda Department of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee kicked up a storm recently when it came out in favor of the English phrase “Year of the Loong,” rather than “Year of the Dragon.” The logic seemed to be that “dragon” as a translation for the Chinese character 龙 (lóng) didn’t adequately express the differences between the Eastern and Western versions of these mythical creatures:

(source: WeChat account 晨枫老苑)

WeChat account 晨枫老苑 (chénfēng lǎoyuàn) published a blistering takedown of the new variant loong, arguing that besides being practically, linguistically, and historically suspect, it was also a colossal waste of time:

I hope that this is just the personal opinion of certain people in the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee’s Propaganda Department, because frankly, this country has many other things that demand our attention, and expending energy on this is a waste.

If they want to use pinyin to “Chinese it up,” 龙 ought to be rendered into pinyin as long, but that would inevitably be confused with the existing English word “long,” so that’s no good. And what is loong, anyway? It conforms to neither Chinese pinyin nor English-language spelling conventions. It’s just a phonetic romanization used by some missionary way back when. It’s baffling and incomprehensible to the vast majority of modern English speakers, and for Chinese people, it doesn’t embody Chinese culture, cultural confidence, or discourse power. It’s not even a Chinese invention at all! And despite sharing an approximate pronunciation with 龙 (long), it doesn’t reflect any inherent characteristics of Chinese dragons. It’s really nothing more than a relic of a semi-colonial era! [Chinese]